There are a handful of factual reasons why this is true. Neil Gaiman grew close to Alan Moore in the early eighties, having recently discovered one of these very comics. Gaiman even worked on supplemental prose in Moore’s Watchmen. The more fun reasons, though, come through within Moore’s ’84-’87 run on Swamp Thing (titled The Saga of The Swamp Thing for the first year, even though the six volume collection of Moore’s four year run is also sold under the same name).

The Bogeyman, from the cereal convention in ‘The Doll’s House’ Sandman story? He started out as a Swamp Thing character. This person believes they killed the actual bogeyman and therefore inherited the chance to fill the role. Swamp Thing kills the successor, in the end. That wouldn’t stop someone from taking up the moniker afterward, though- just like he did.

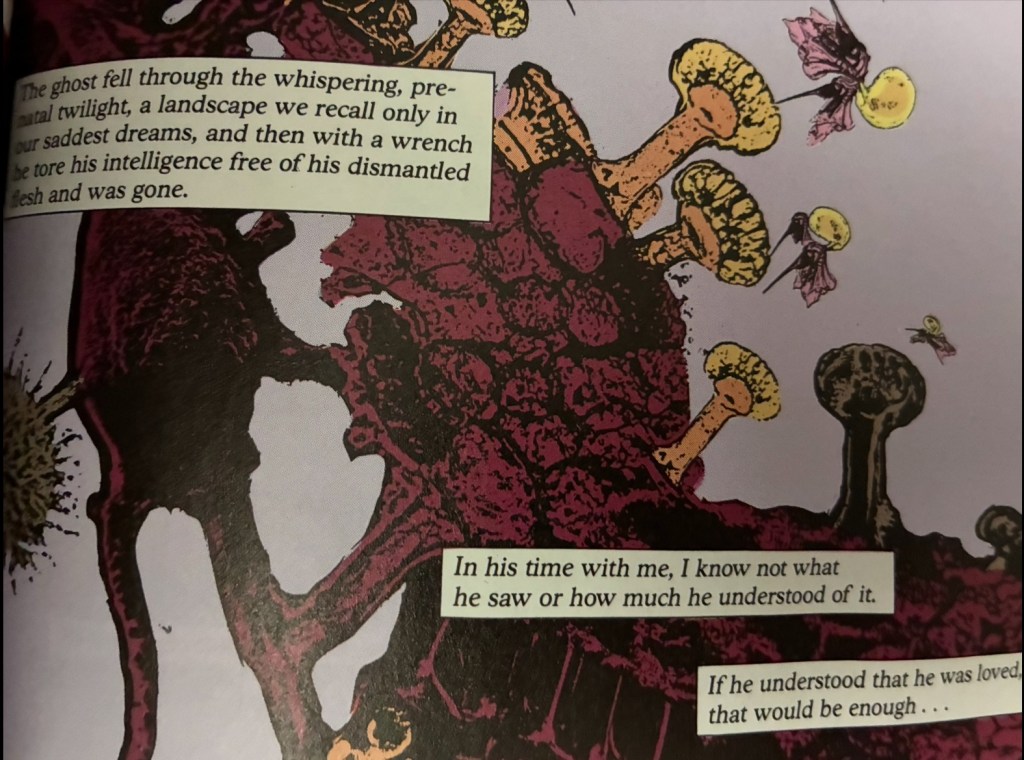

Before Matthew Cable dies, he manifests the power to make dreams and imaginings real. When he dies, he receives a mysterious reassurance of a purpose waiting for him beyond the veil. Perhaps a cawing, eye-ball-gulping purpose.

Yes, Cain and Abel in their twin Houses of Secrets and Mysteries existed in the world of D.C. comics before then. But a fan of the original Sandman would recognize them exactly in Swamp Thing. Their appearance and behavior are identical…which meshes with something that’s been on my mind since I read Promethea and Sandman: Overture. The mother of the Endless- Night -looks almost exactly like a being called the Lady in Promethea. Considering the role of these figures in both stories and the closeness of Alan Moore and Neil Gaiman, I find it hard to believe that the resemblance is coincidental.

(Speaking of: there is a brief Swamp Thing story about aliens aboard a ship which they named Find The Lady. This usage of the word ‘lady’ refers to a planet)

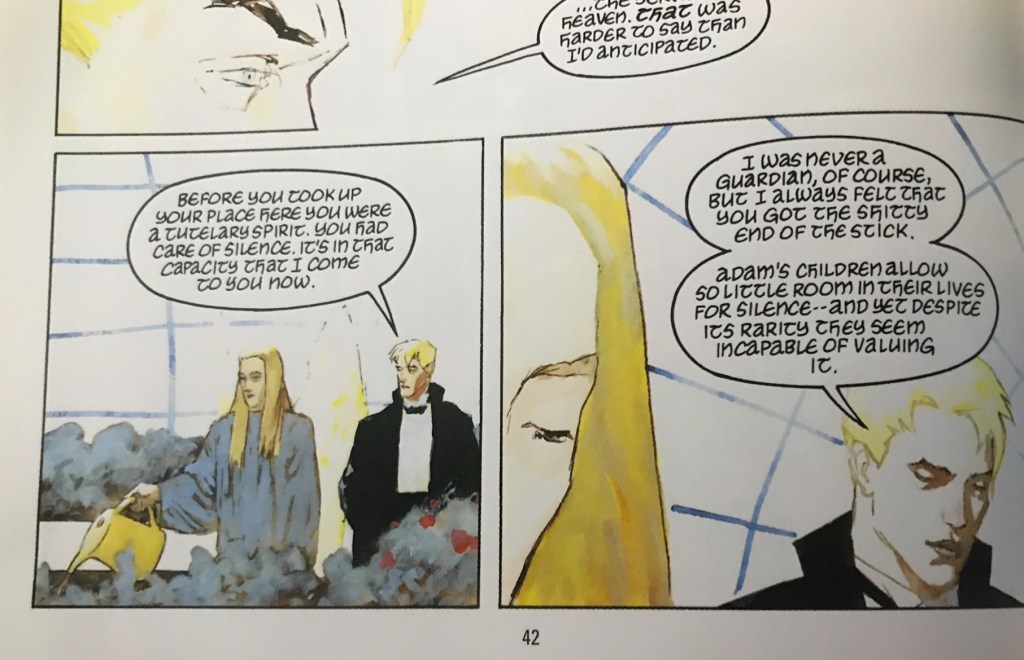

In Swamp Thing, Cain and Abel dwell in a collective psychic space between worlds. Travellers between different planes sometimes encounter Cain and Abel. Cain and Abel are also capable of perceiving cosmically significant events before they make contact with the material world (even if they bicker over it like a homicidal sit-com duo).

Another piece of relative common ground: the Phantom Stranger, Boston Brand, Etrigan and John Constantine. Constantine and Etrigan are the only direct Sandman links out of those four but Neil Gaiman’s Books of Magic is directly adjacent to The Sandman. Both Constantine and the Phantom Stranger are major characters in Books of Magic. Dr. Occult, Boston Brand / Dead Man, Zatana, Zatara, Baron Winter, Doctor Fate and the Spectre also appeear in both Swamp Thing and Books of Magic.

To say nothing of the importance of John Constantine in both of those and The Sandman. What’s funny: I originally had the desire to read Moore’s Swamp Thing run because I had just finished the SU story Hellblazer: Dead in America. What do I find? The first ever appearance of John Constantine as a fictional character. In a story arc which ‘Dead in America’ echoes very closely.

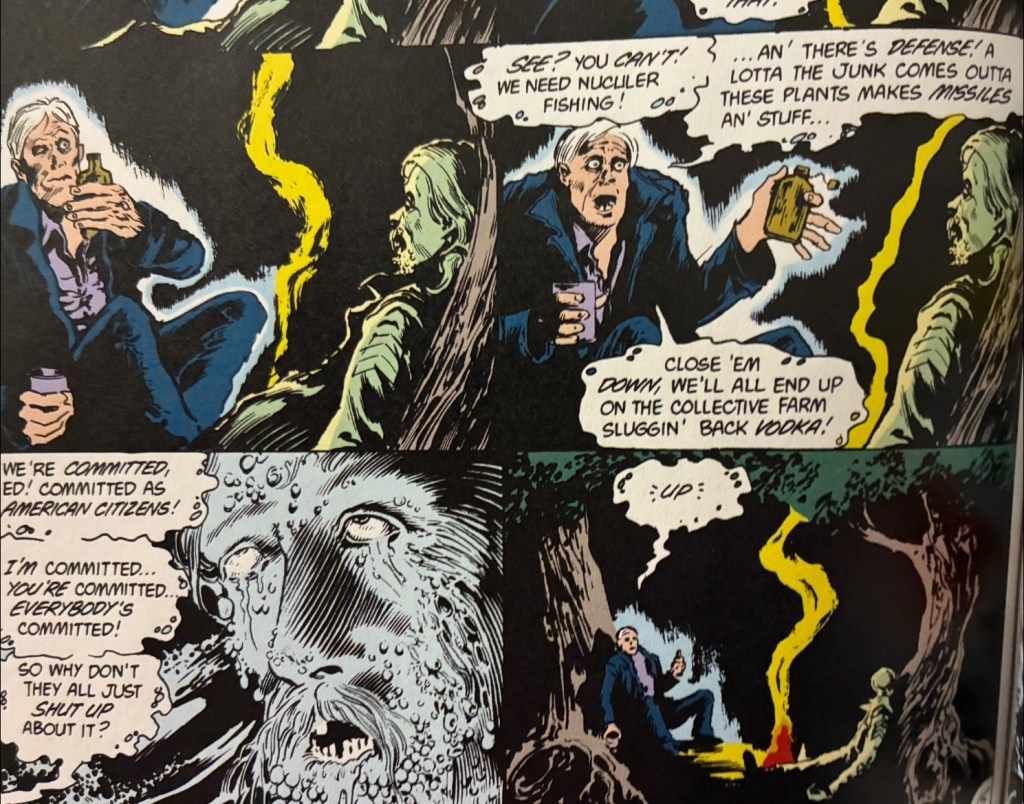

Alan Moore basically invented Constantine to connect Swamp Thing with the wider plot threads in the American Gothic arc. My wife recently showed me the early nineties TV show. I vaguely remember that my mom used to watch it but nothing about what it was actually like. I also suspect that the TV show was addressing an audience with a broader awareness of the character than mine. I just read the Alan Moore stuff. Before the early eighties, Dr. Arcane was a big enough re-occurring villain for him to be filed away as the obvious big bad. The early nineties show also decided to make Dr. Arcane British and gave him a few lines making vegetible jokes. Swamp Thing and John Constantine have this romantic American / snarky Brit dynamic…which they couldn’t have been trying to shift onto Swamp Thing and Arcane…could they?

Arcane definitely matters in the Alan Moore stuff but mostly by the consequences of previously depicted actions. His pro-active involvement in Moore’s Swamp Thing starts when he manages to rope Abigail Cable into Hell, sending Swamp Thing on a Divine Comedy-like journey. Like Timothy Hunter, Swamp Thing’s quest across dimensions puts him in touch with both Boston Brand (in the realm of the recently dead) and the Phantom Stranger (in Heaven). Etrigan, of course, shows up in Hell.

The long, interdimensional treks are some of the more chaotic and interesting moments in the comic and the Divine Comedy themes are never altogether gone from that point forward.

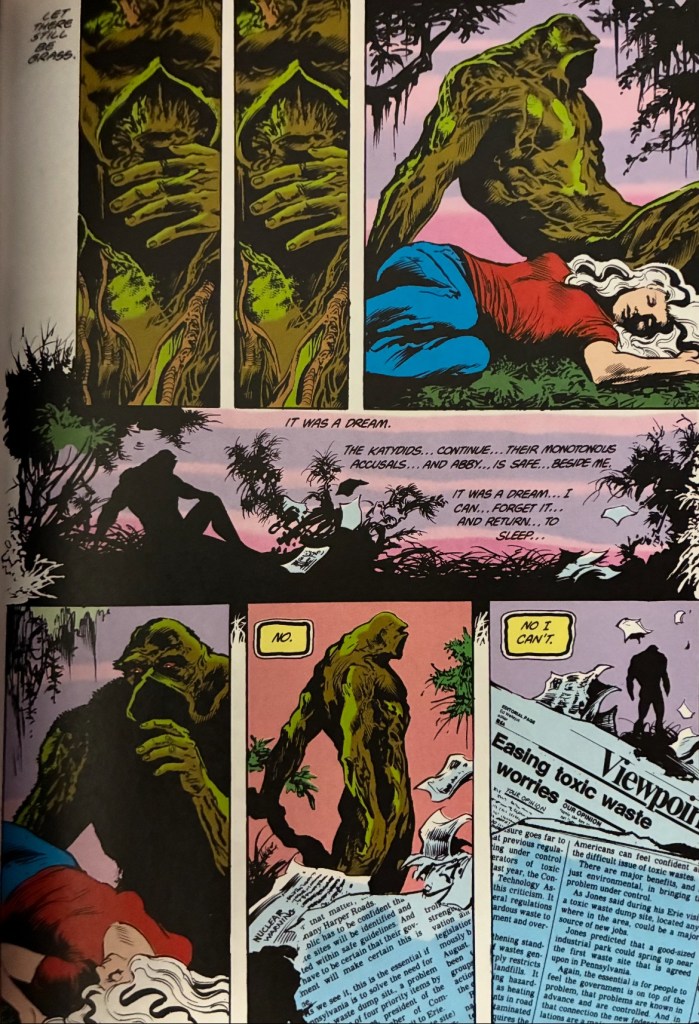

Like Dante and Beatrice, a lot of the astral travel (at this point and elsewhere) is catalyzed by the romance between Swamp Thing and Abby Cable. It’s interesting to me how often the journey of the Orphic pilgrim is prompted by the need to find someone- usually a lover, even if Hans Christian Andersen did his best to blunt those edges in The Snow Queen.

Alan Moore did a sympathetic version of The Creature from the Black Lagoon decades before The Shape of Water. The Dantean themes add something to this. Regarding the woman whom he modeled Beatrice after, Dante said that he wanted to write about her in a way that no woman had ever been written about.

I just remembered- there are three prolonged journeys across dimensions in Moore’s Swamp Thing. The first is rescuing Abby from Hell, the second is confronting the menace at the heart of the American Gothic story and the last is a long, hard journey toward reunion after a painful separation. Three journeys across worlds, like the Divine Comedy. Also like the Divine Comedy: the last one happens mostly in space.

Or, at least, you could be forgiven for thinking Il Paradisio happens in space. He describes Heaven as a bed of stars, surrounding a central light. Different souls are like planets unto themselves. One travels between stars and planets by looking at them.

Before entering Heaven, Dante must drink from the waters of Lethe, to cleanse himself of his human fallibility, which causes a fundamental shift in his perspective. He romantically loved Beatrice while she was alive but in Heaven spiritual love reaches full maturity and the mortal perspective is removed by Lethe.

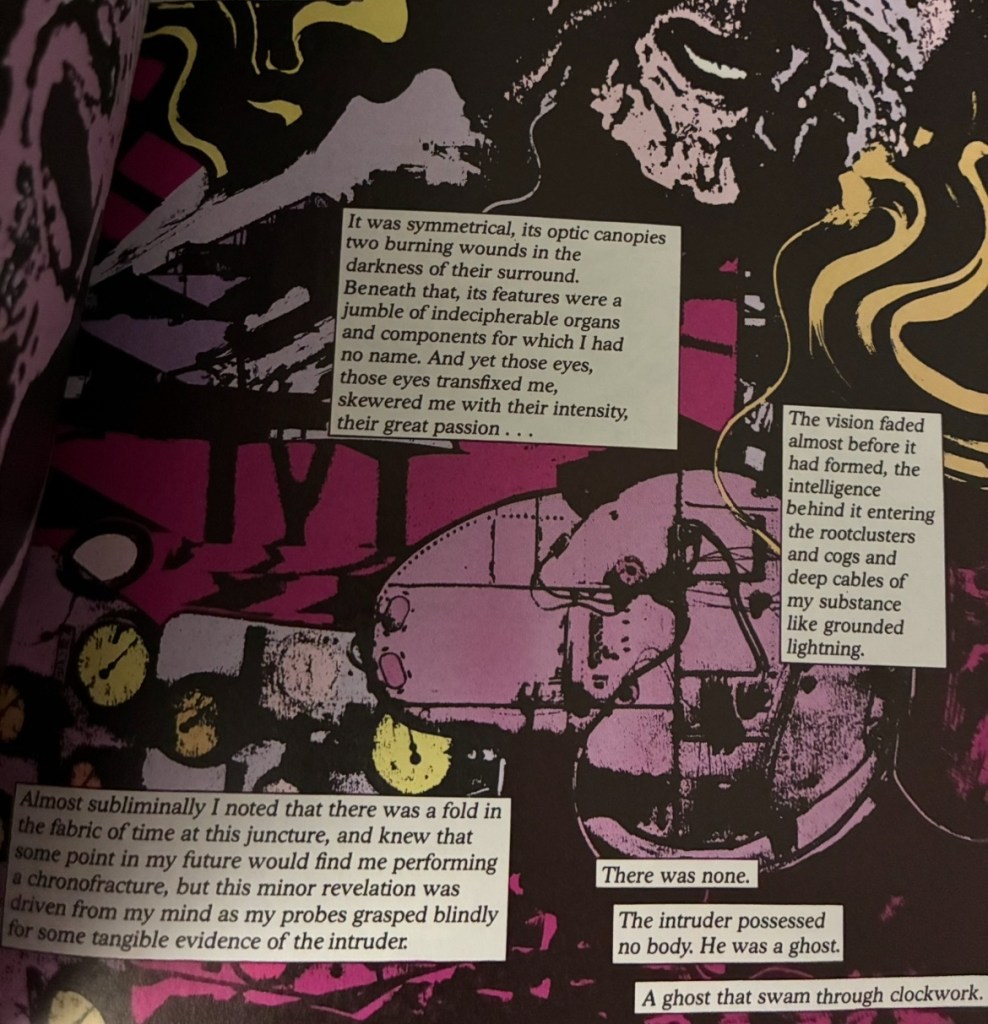

Swamp Thing is driven from Earth by a weapon devised by Lex Luthor. Yes, he is a plant elemental with the ability to manifest anywhere that plants live (Swamp Thing, I mean). But what Luthor’s weapon did was separate his subjective point of view from Earth’s plant life, forcing Swamp Thing to look for a manifestation vector outside of Earth.

He makes a few different stops before he is able to manifest long enough to set out for Earth. The love between Swamp Thing and Abby deepens. This is, however, far from pleasurable. Swamp Thing wrestles with the prospect of total separation. Abby goes through the same thing and a mysterious encounter with John Constantine occurs.

I wondered if this related to the entanglement referred to throughout ‘Dead in America.’ That, it turns out, occurred after Moore’s work on Swamp Thing.

Swamp Thing and Abigail both experience an interrogation of their love. Swamp Thing tries to abolish the whole thing from his memory, then tries to embody a museum of nostalgia on another world, including his own lifeless recreation of Abigail.

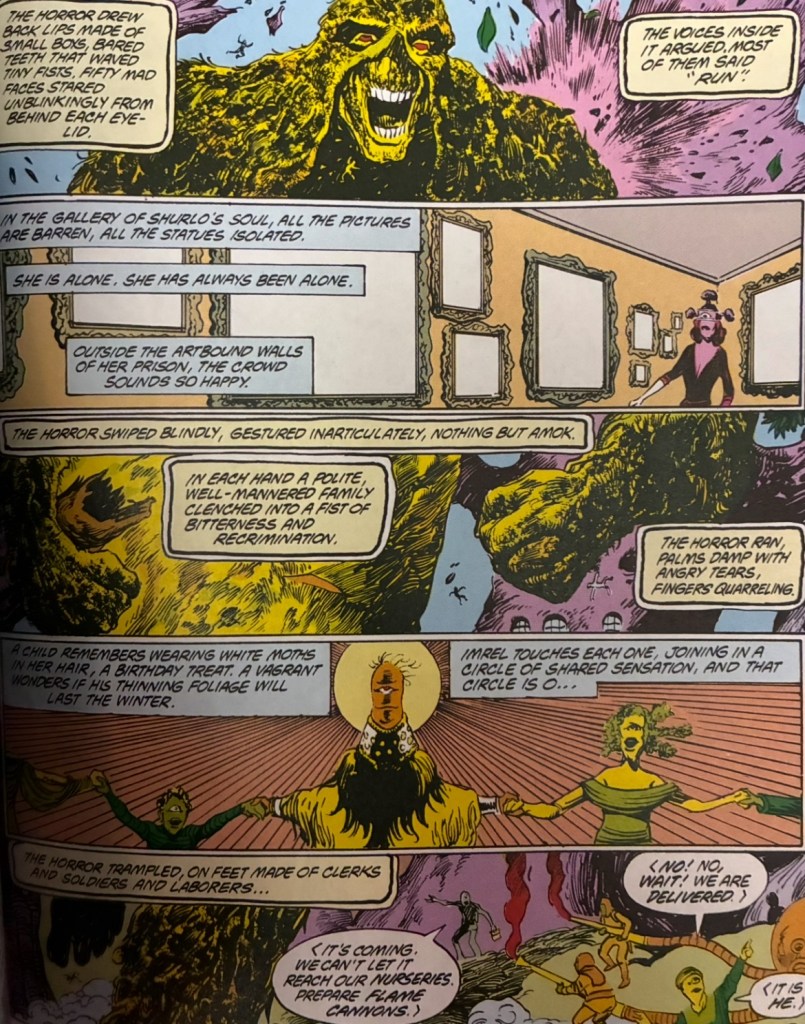

A demonic echo of Abigail’s uncle- Dr. Anton Arcane -briefly reaches out to her from Hell. Because of his psychic contact with Abby, Arcane turns into a blocky, Frankenstein’s-creature-type-wight embodying Abby’s buried and sublimated feelings toward various masculine figures in her life.

With all the older, male, broad-shouldered remembrances, it is difficult not to notice the subtle resemblance to Swamp Thing. As if Abby is beginning to shake off her “daddy issues” and is now re-evaluating her relationship. In the end, she finds that her love and loyalty are still justified.

This really reminded me of the 2019 Alejandro Jodorowsky comic Angel Claws, which tells a similar story with more dream logic and sex.

Relationship problems were not the only way in which Dream of the Endless echoed Swamp Thing.

I wondered if, given the range of Swamp Thing’s abilities and domain, Dream must necessarily have some connection to him. This is demonstrated in Moore’s run on the Swamp Thing comics but it was made explicit and canon in the recent Hellblazer story ‘Dead in America’.

As expressed in ‘Dead in America’, Dream rules over dreaming sentience (the Dreaming) and Swamp Thing rules over dreaming non-sentience (the Green). The living non-sentience Swamp Thing communes with are (obviously) either plant life or things directly adjacent to it, like mycelial networks.

At the very least, there’s got to be some aspect of the Green that overlaps with the Dreaming and some aspect of the Dreaming that overlaps with the Green. I find it easy to think that they are different emanations of one another, perhaps like how the shape of an Endless depends on who is looking. Swamp Thing may literally be Dream in the plant world.

There are serious differences in perspective, though.

Dream is a monarch, with duties set in stone, as a perpetual condition of his existence. Swamp Thing exists within the same holistic network as all plant life and this connection compels his love and loyalty to the planet. He defends it as a champion and is capable of preventing outside threats. He feels obliged to take a protective stand when necessary but does not identify completely with his custodial authority, as Dream does.

I wonder if a lot of those existential ‘purpose’ questions disappeared with the realization that he is his own being, rather than Alec Holland.

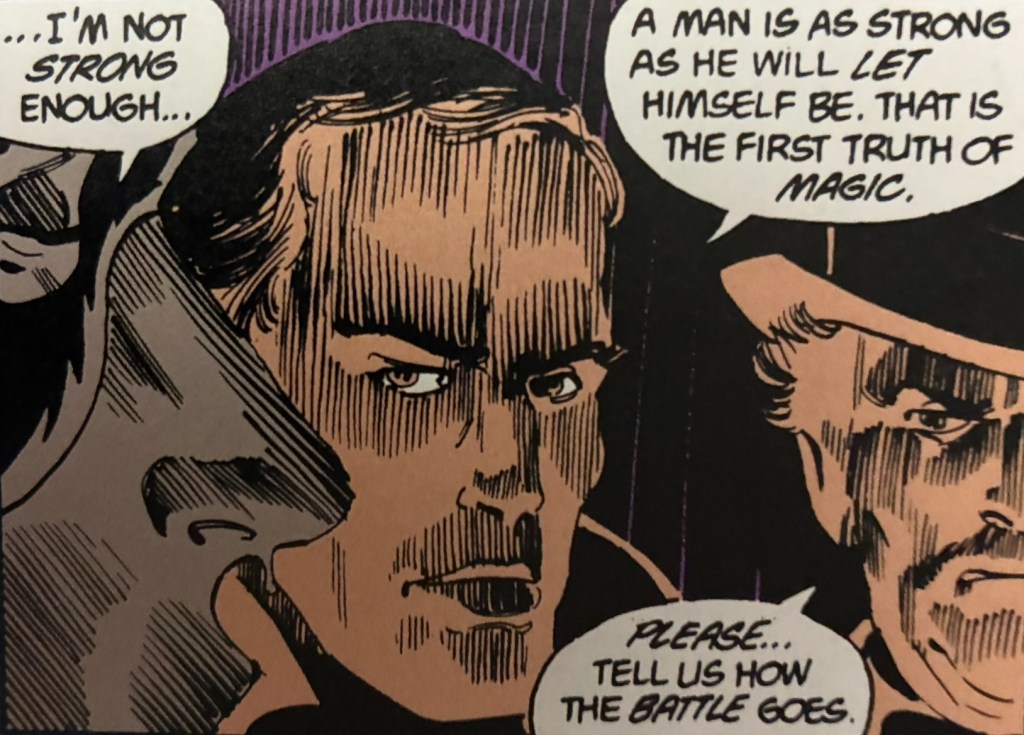

Also on the overlap between Dream and Swamp Thing: Swamp Thing’s protective duty to the planet carries him all the way through the American Gothic arc, leading up to the confrontation with the primordial darkness outside of creation, charging into battle alongside the Phantom Stranger and Etrigan. It is important enough for Swamp Thing to bet his life and his sanity on it.

However, Abby Cable re(?)entered Swamp Thing’s life after he realized he wasn’t Alec Holland. He fell in love with Abby at the same time that he was coming to terms with his true nature. Her love has anchored much of his stability, up until that point. The loss of this anchor is also reminiscent of Dream’s mortal relationships in The Sandman. Swamp Thing is different, though, in that he never flinches from the long, hard road toward reconciliation.

This split in loyalties does not haunt or paralyze Swamp Thing like it did Morphius. What haunts and paralyzes Swamp Thing is losing Abby. Morpheus will agonize over an ex but his priorities are always crystal clear: the Dreaming above all.

The ending of the American Gothic arc also makes me wonder about the cosmological relevance of Lucifer.

This is going to get into the weeds of my interpretation of Mike Carey’s run on Lucifer. The story begins with the Silver City approaching Lucifer with a big payment for a big favor: get rid of an emerging deity.

This being once belonged to a pantheon called the nameless gods. These are divine spirits that respond to non-specific or non-linguistic prayers. The ones who respond to spirits reaching out with no point of linguistic contact.

Later, another group of beings enters the plot: the Jin En Mok, who were the deities that remain from an earlier universe, who typically see our universe as an obstruction or an enemy. One group are the survivors of a defunct pantheon and the other are the gods of those with none in particular. Those sound like two groups that could easily overlap- potentially two societies within the same race.

The latter arc of Mike Carey’s Lucifer concerns a character called Fenris Yggdrasil. Fenris entered existence as the Fenris from Norse mythology. Since Lucifer takes place within the continuity of The Sandman, we can assume that this Fenris is an emergent dream-construct, like the deities throughout both The Sandman and American Gods. In other words, he sprang from the oneiric energy of believers, from when his existence was more widely credited. By the time he shows up in Lucifer, Fenris is trying to tear down the multiverse. If he ever succeeded at doing that, it would make him a refugee from another universe like the Jin En Mok.

The human family that the nameless god from the beginning of Lucifer incarnated into begins and ends Mike Cary’s story, what with Lucifer holding the destiny of the soul of the nameless deity over one of the members of the family he incarnated in (Rachel Begai).

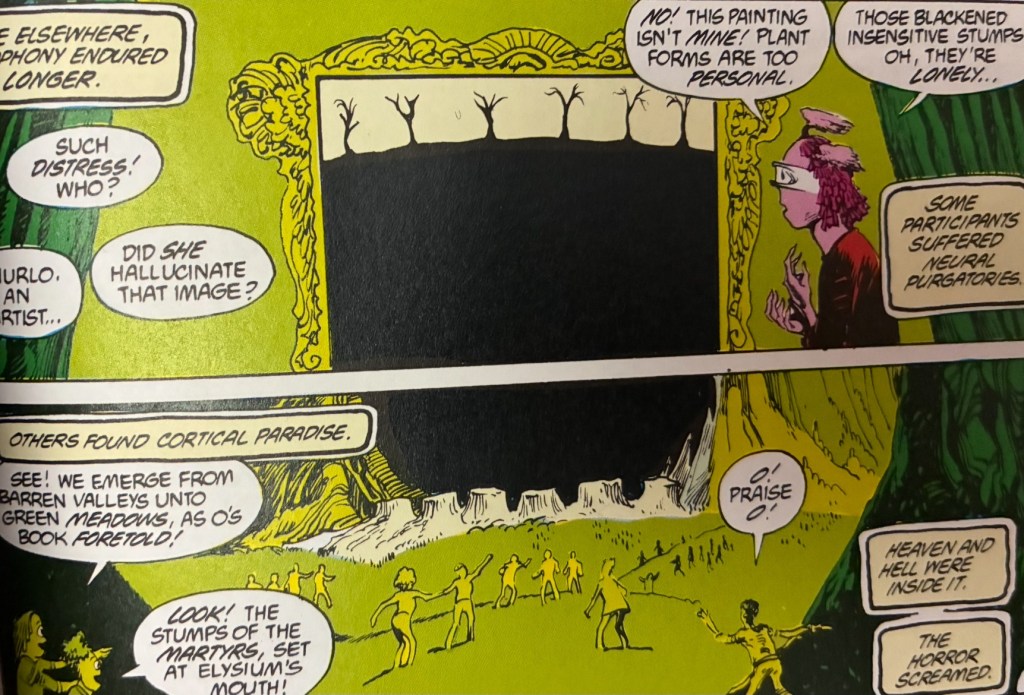

At the culmination of American Gothic, Swamp Thing, Dead Man, Etrigan, Phantom Stranger and other astral combatants meet the darkness outside of creation in battle.

This was the opening of a cosmic floodgate, enacted by the Brujeria. This is the darkness outside of creation encountering existence for the first time. Existence and definition. It learns to identify as evil, from the blandishments of Etrigan and Phantom Stranger. Swamp Thing recalls the words shared with him by the Parliament of Trees: “Where, in all the forest, is evil?” Swamp Thing tells the darkness (after being absorbed by it) that evil is the best and most nurturing companion of good, which makes an impression on the young mind.

Smitten, it turns to embrace its cosmic opposite. A giant finger rises from the astral battle field, bringing with it a great, dark hand, reaching out in affection to a golden hand of light.

The menace represented by the primordial darkness was described, by Constantine, as a threat to the multiverse. It existed before creation, being either the space that creation was built within, the substance of which it was made or perhaps both. The origins and manifestations remind me of both the Jin En Mok and the silent gods.

Then…there’s my ususal stalking horse with anything connecting to the Sandman universe.

Both The Sandman and Books of Magic take place within the same multiverse. Punctuated, as usual, with things like timeless regions- ‘soft spots’ and skerries of the Dreaming. The Dreaming itself is beyond space and time. Both Sandman and Books of Magic also include monsters that reach across planets and timelines. I’ve talked a lot on this blog about my theory that the mad star from Sandman: Overture also includes the extradimensional region called the Gemworld mentioned in Books of Magic. As in: they are different facets of the same infernal, eldritch conglomerate.

It seems possible, to me, that this conglomerate might also include the primordial darkness from Swamp Thing. Given the behavior and origins of the Jin En Mok in Mike Carey’s Lucifer run, it is fair to assume that they share interests with the conglomerate. Then there’s the second camp (or another name for the same one, if you prefer- I do)- the nameless gods. They are the quiet layers of divinity sensitive to inarticulate prayerful yearning. The primordial darkness in Swamp Thing behaves a lot like a divinity that has either never learned to talk or was never before able.

All that is incidental to how great these comics are, though. The chemistry between Moore and Gaiman was such that their works do not feel like they have the derivative relationship that they must necessarily have. The common ground is seamless enough to feel like the same continuous, simultaneous creation.