Spoiler warning

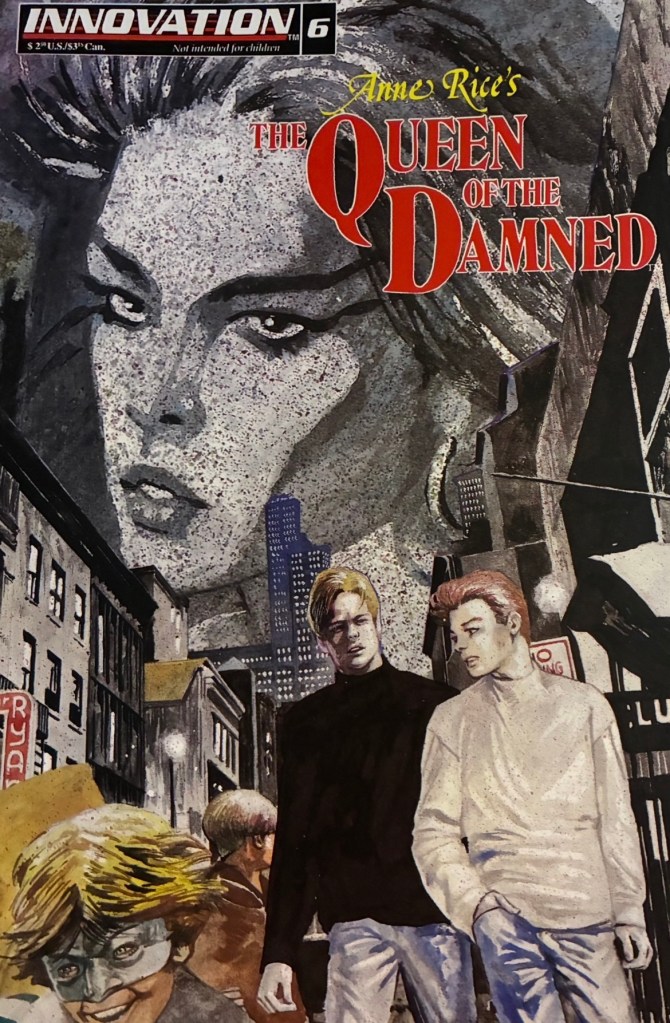

While the absence of Lestat as the narrator makes things less immersive than the Vampire Lestat comic…the original Queen of the Damned easily translates into pictures and word balloons, what with the number and diversity of characters, events connected by vast distances and vampires breaking cover. Anyone looking for a straight-laced adaptation would have little to complain about. To the best of my memory of the book…I think every single scene made it into the comic with varying (but admissible) degrees of faithfullness.

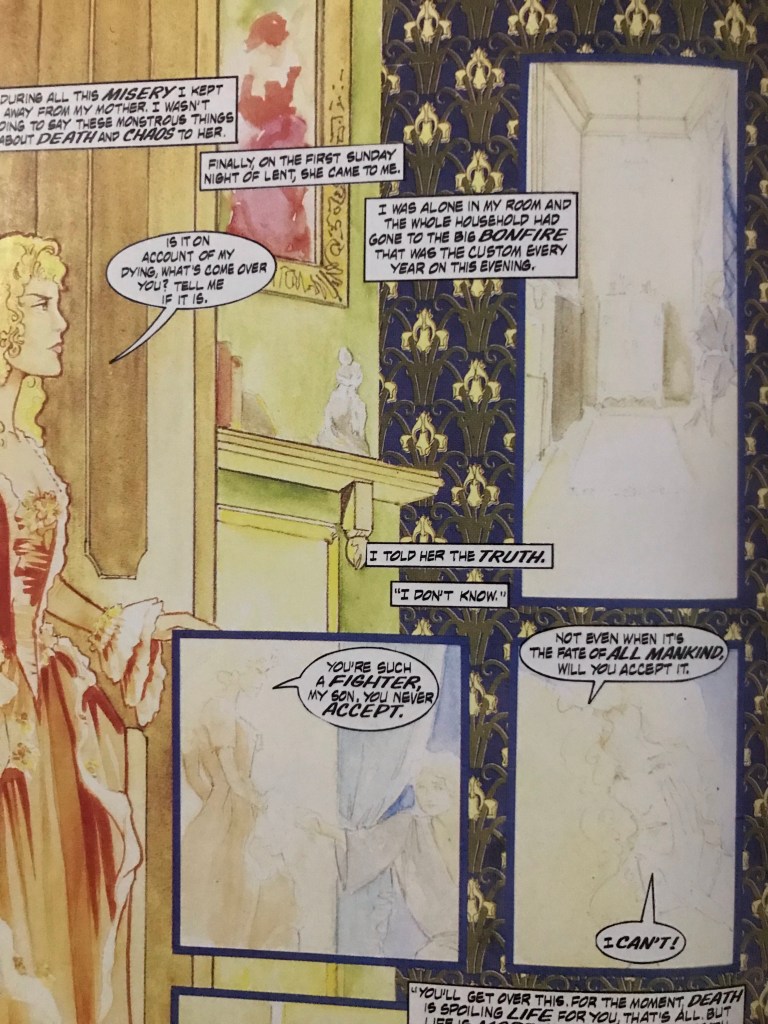

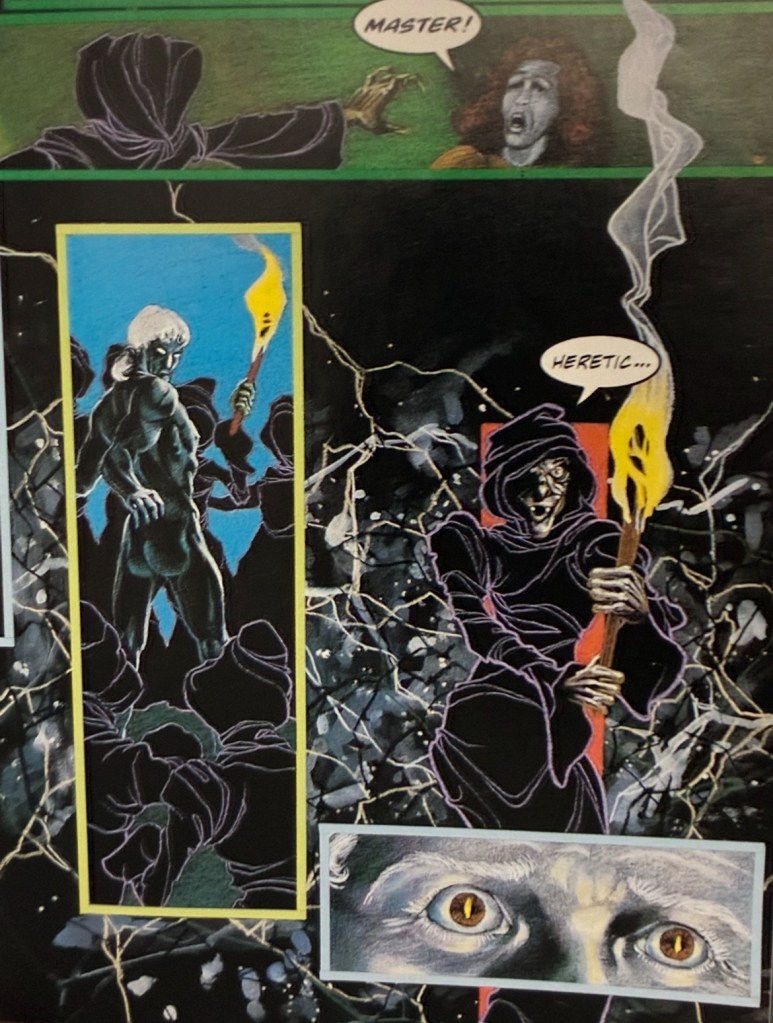

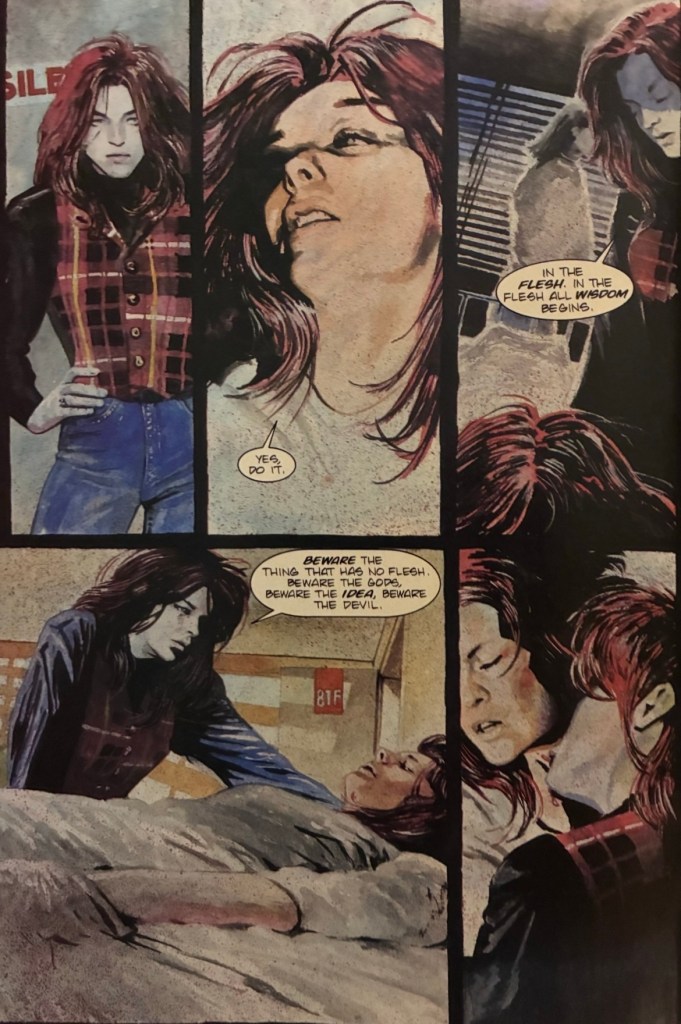

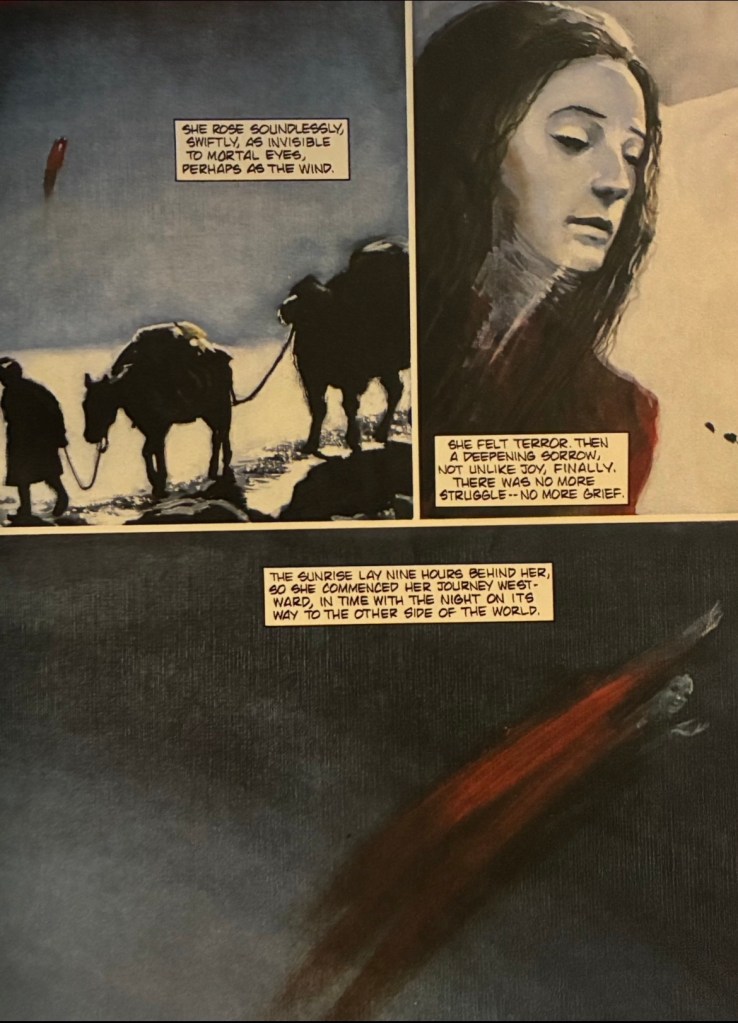

The art is neat to. A few scenes, like Maharet visiting Jesse in the hospital, almost remind me of Dave McKean, who would have been a rising star in comics at the time. The scene below reminds me of McKean’s art in Neil Gaiman’s Black Orchid, which felt equidistant between genre-savvy comic art and photo-realism. And, of course, a ton of shadows and pale lighting (most of Black Orchid happened at night to).

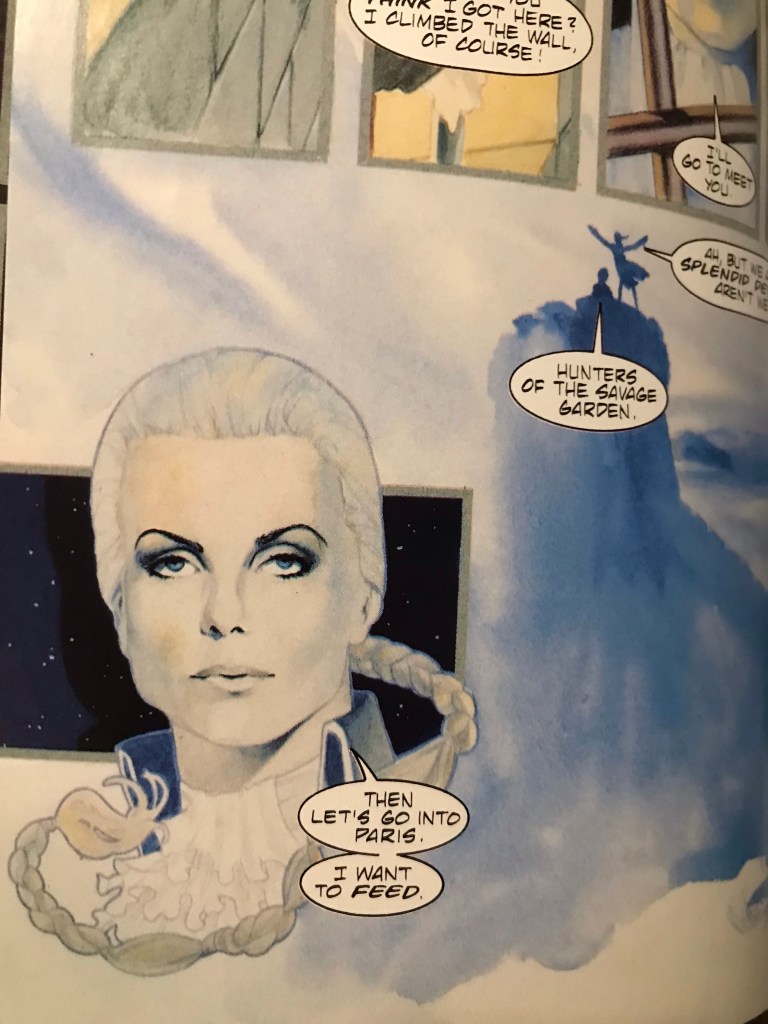

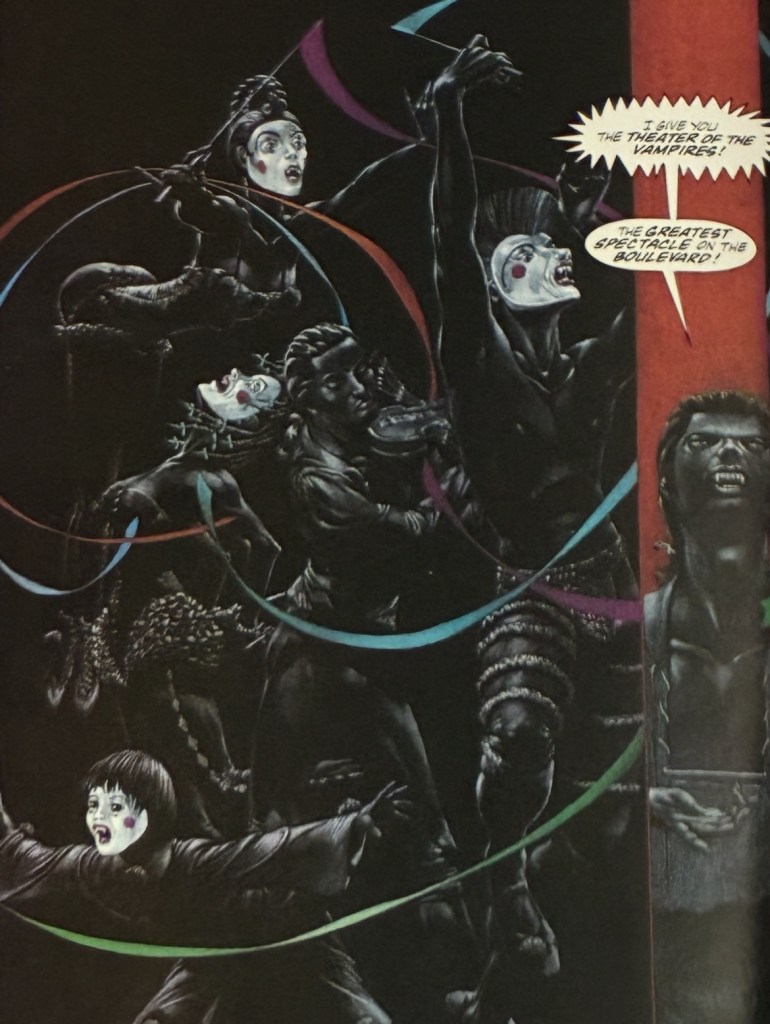

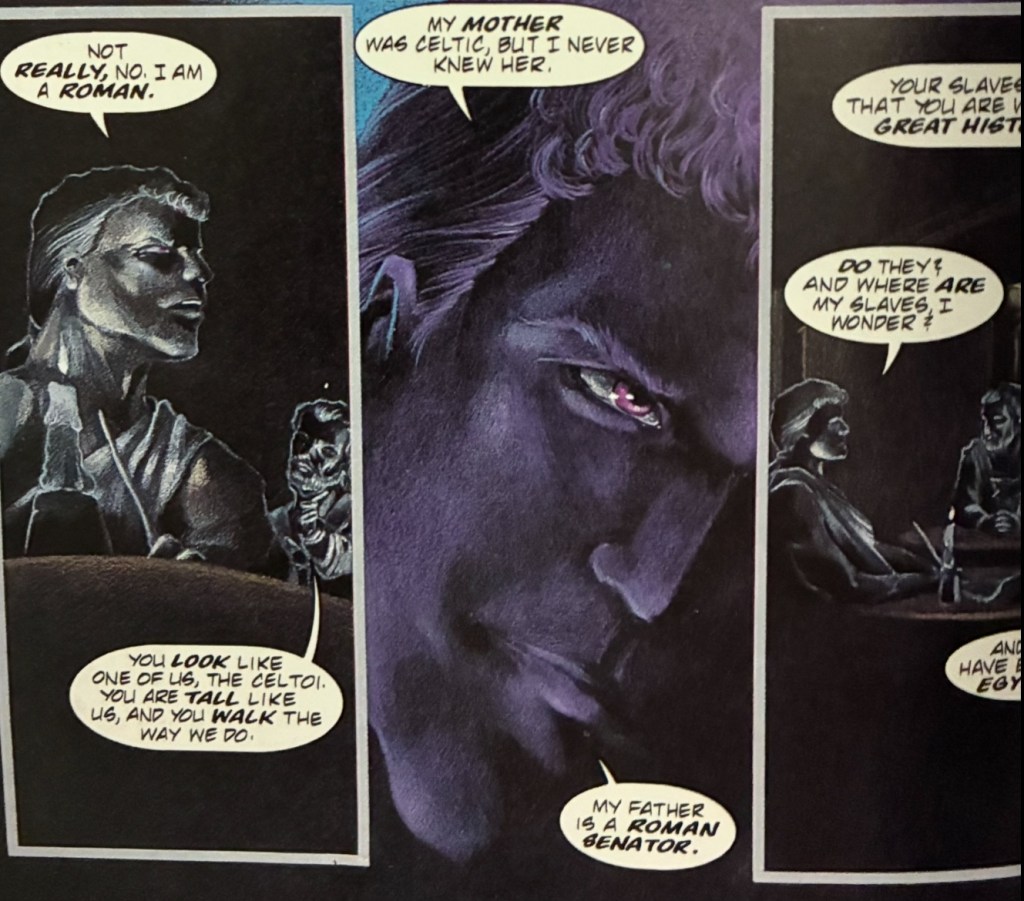

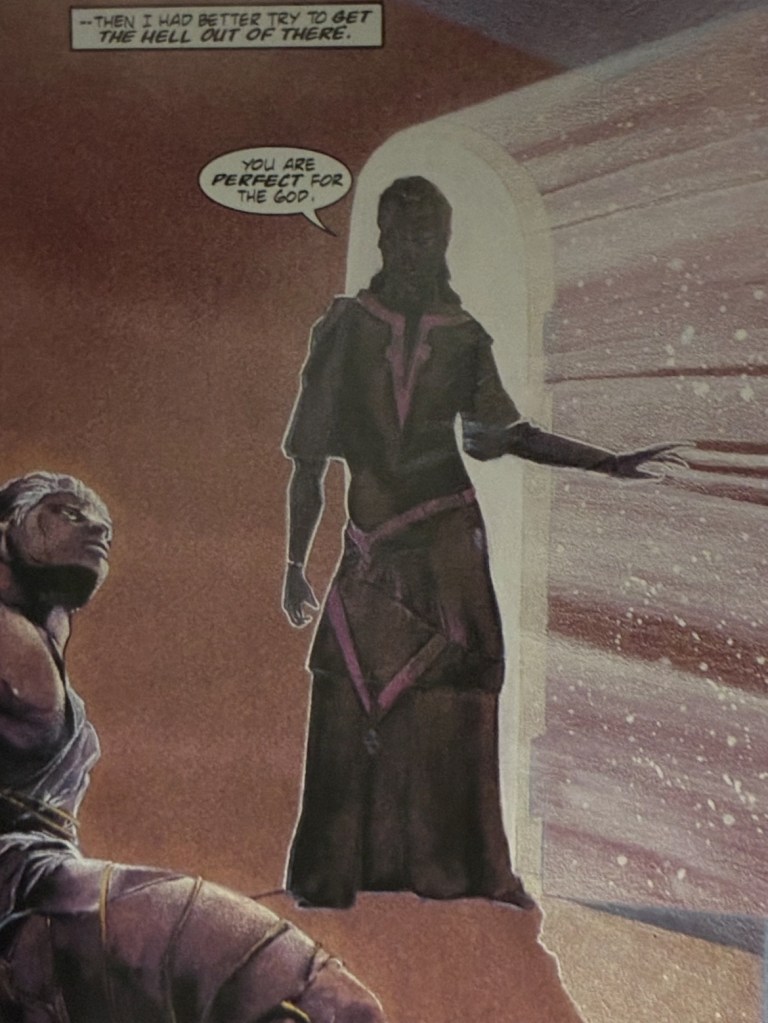

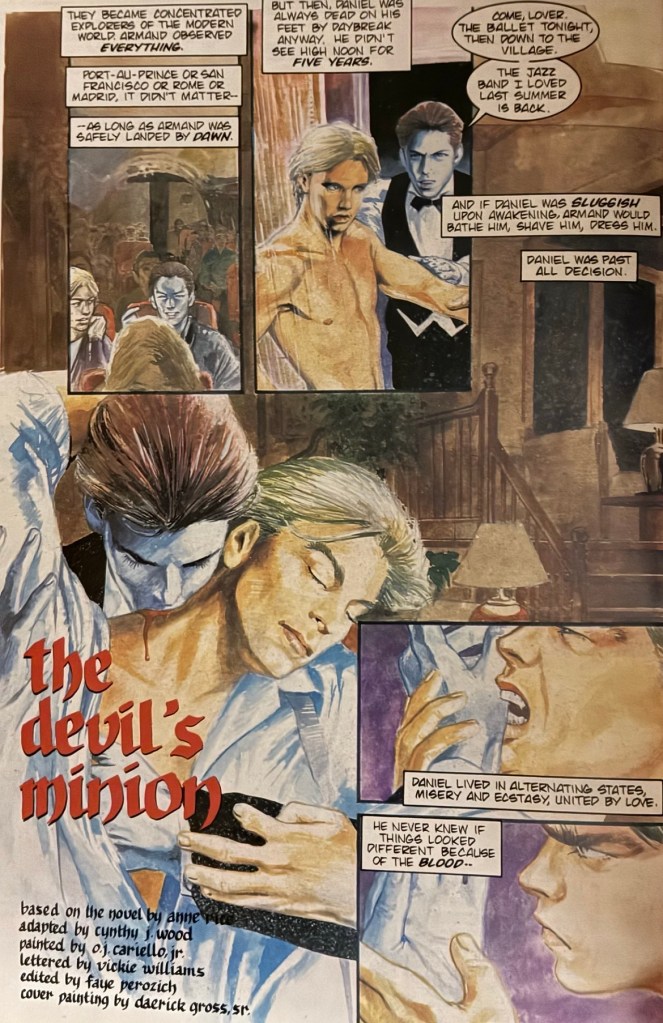

The degree of realism also roots us in the present of the book- 1984. I was a little surprised by Armand’s twentieth century presentation, here. My impression of Armand (as depicted in the books) was of someone who is recognizably non-binary, erring slightly toward femininity.

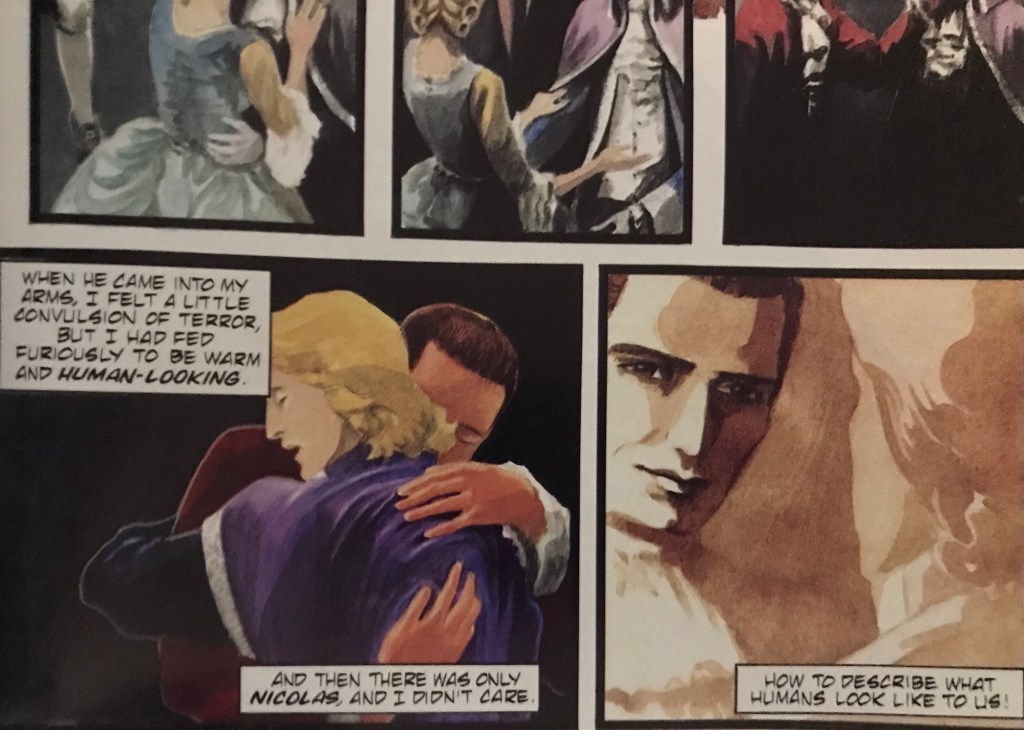

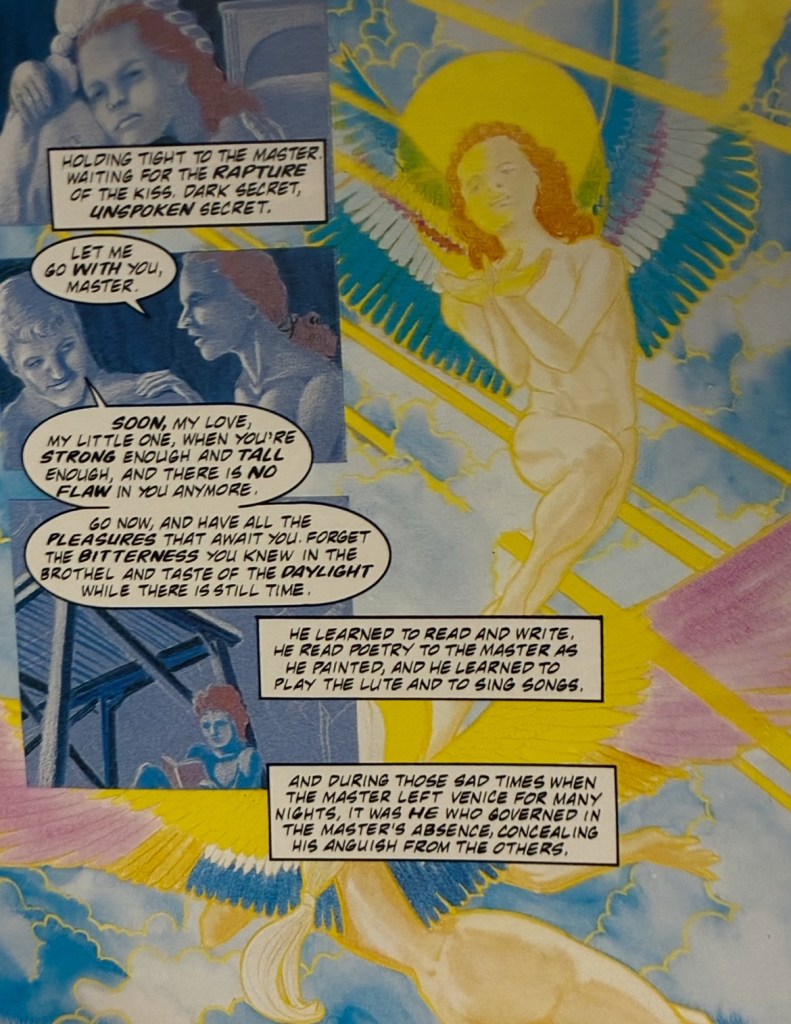

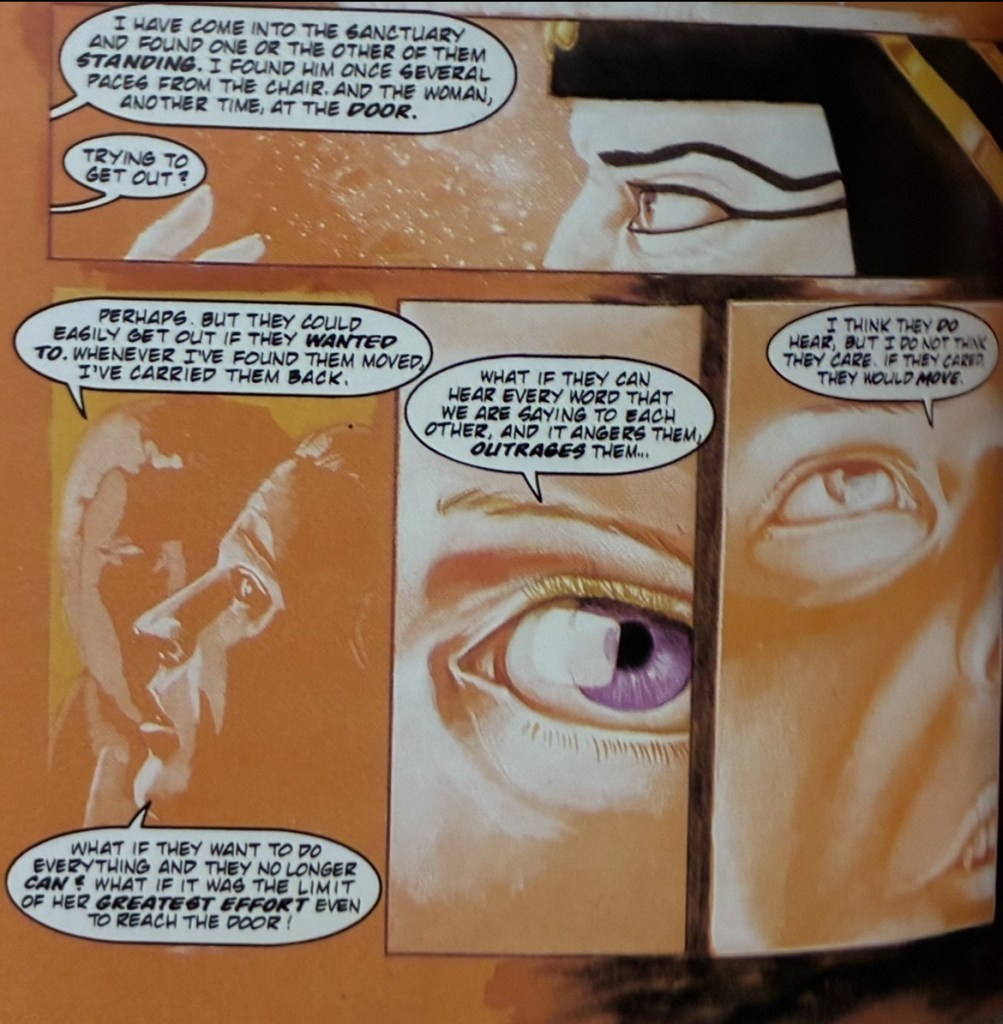

This is where the diminished immersion became a bit more clear to me. When I first read The Queen of the Damned, the relationship between Armand and Daniel was one of the sweetest and most engaging parts of the whole book. That was probably when he started to become one of my favorite characters.

One thing they could have done was spend more time in the early stages of the rapport, when it was at its most chaotic. The restaurant encounter- when Armand orders literally everything on the menu because he wanted to order for Daniel but didn’t know what he liked -should be its own scene. It’s depicted here but I would have liked to have spent more time in that moment. It also would have been nice to see more of the early, late-night visitations, when Armand surprises him at one in the morning because he wants to talk about the book he saw on Daniel’s nightstand. Or shaking Daniel awake because he wants to talk history and philsophy. Spending more time in the early, uncomfortable stages would have made the tender moments hit harder. To be fair; all of those moments are depicted in the comic but only briefly.

Not endemic to the comic but Anne Rice in general: a lot of her vampire-human relationships are more interesting for not having the moral framing of recent stories. There’s a huge market out there for people who love morally inoffensive vampires. Anne Rice never made any bones, whatsoever, about vampires being non-human beings with non-human perspectives. If Armand and Daniel are an example of the encounter ending (relatively) well then The Tale of the Body Thief shows us both the delicious and horrific possibilities. A happy ending is possible but it can end a million other ways to.

I wonder if Stephanie Meyer would have triggered the backlash she did if she was less eager to make Edward Cullen morally white. I never read Twilight but I saw parts of the movie and it seemed so determined to make Edward cuddly that his predatory, vampiric behavior was just…a bald inconsistency. So when he started doing predatory things to Bella, it smacked of hypocrisy and Meyer’s determination not to acknowledge that darkness raises the spectre of actual, sublimated misogyny.

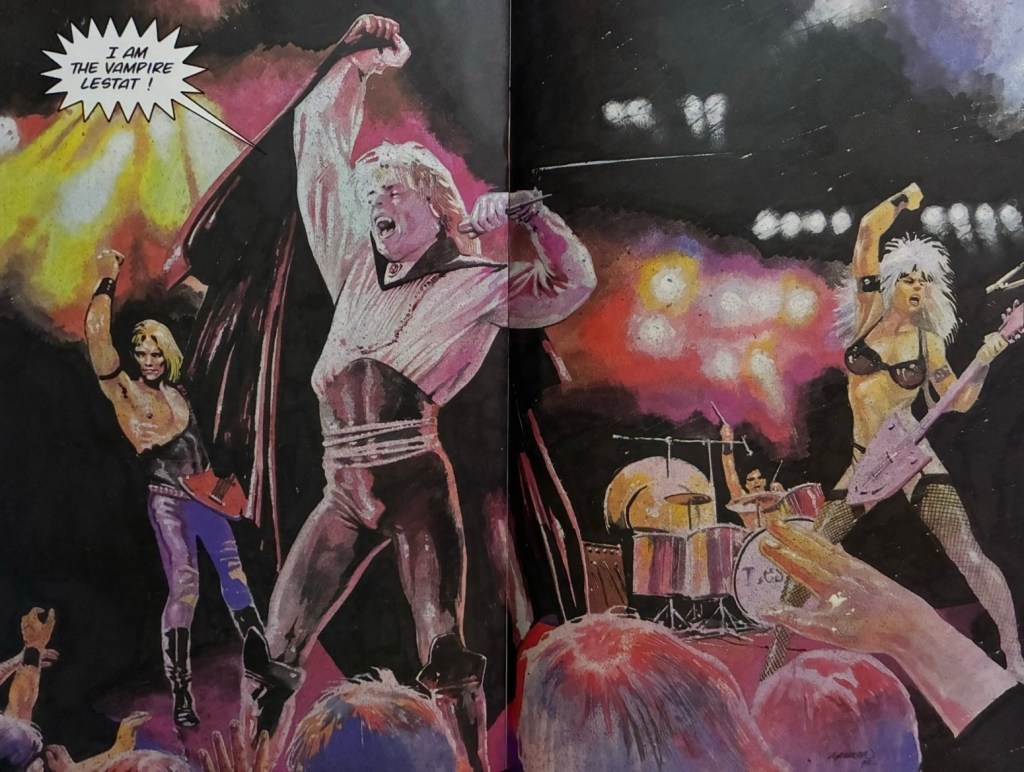

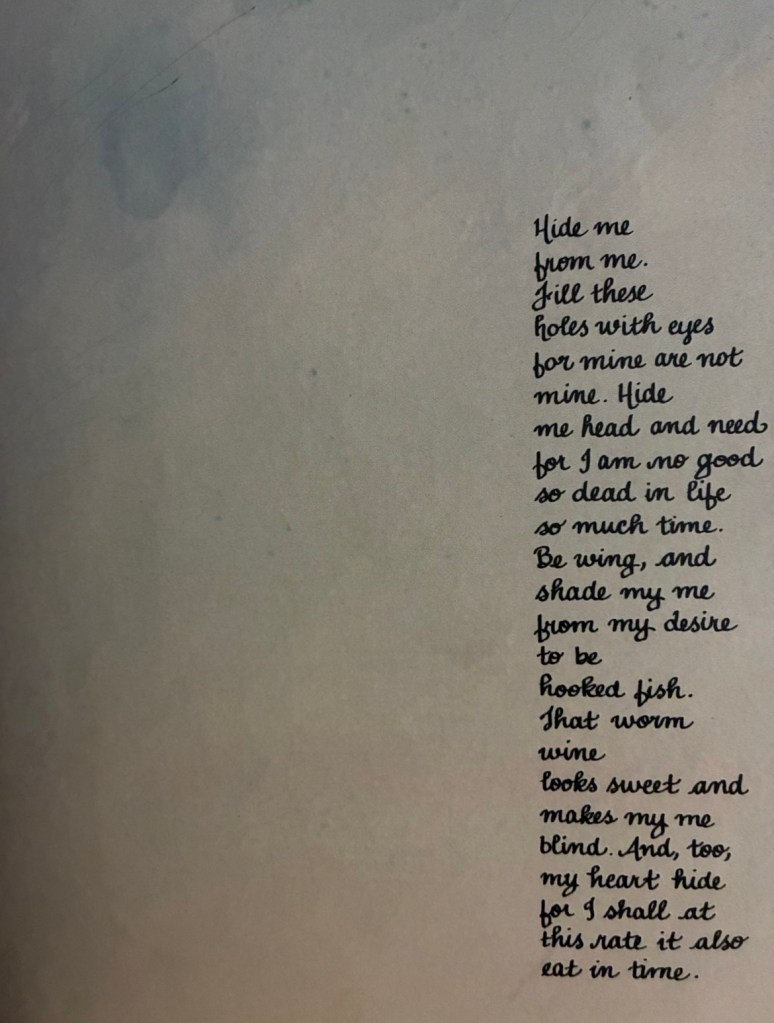

This was also neat. I really liked the Stan Rice poetry that Anne used as epigraphs so often. The Cannibal poem is the only Stan Rice epigraph here but its usage establishes a nice, solitary and emotional beat before we see Lestat in the arms of Akasha for the first time.

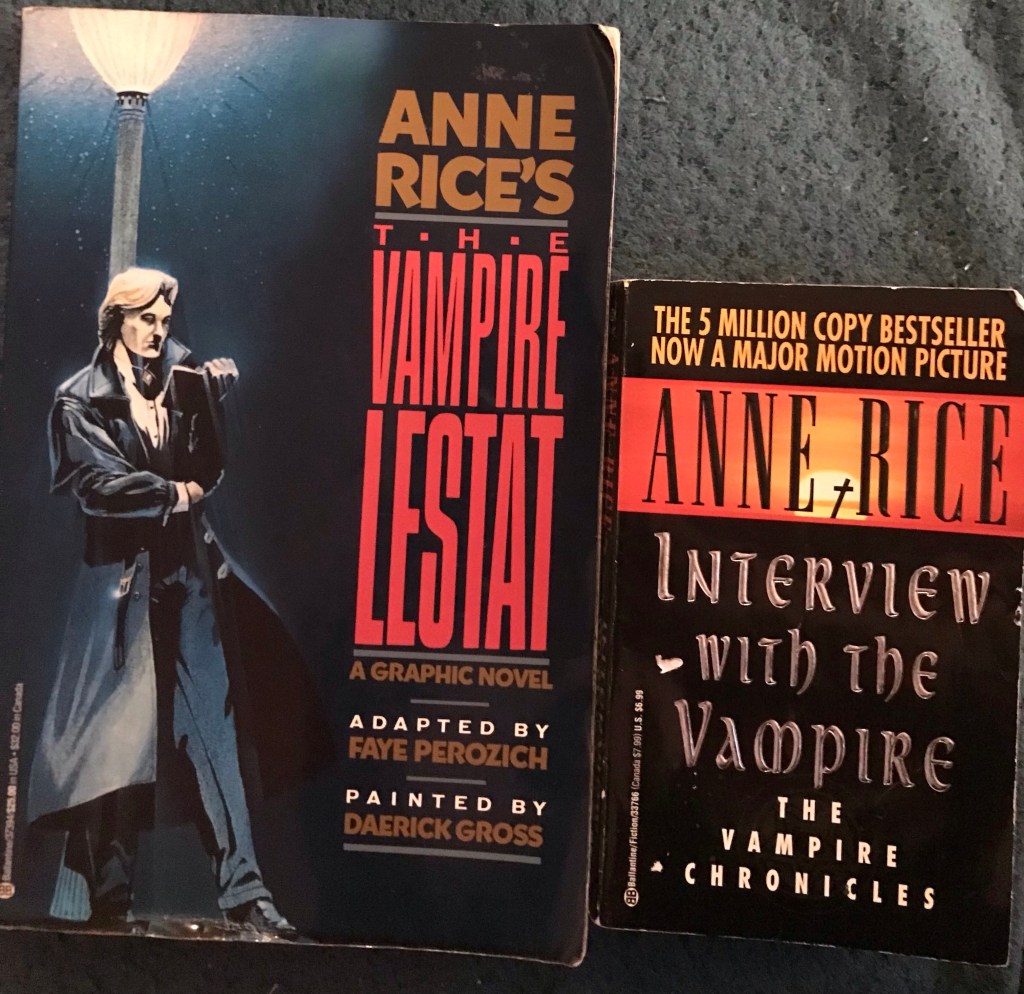

Only eleven of these comics were commercially released before Innovation Comics went under but the twelfth surfaced online last summer.

As of this writing, the portrayal of the final confrontation is the most faithful out of any adaptation (fingers crossed for some later season of the AMC show?).

The Queen of the Damned film didn’t even make an effort. Just a giant vampire brawl.

See…the confrontation in the novel was a debate. Not a single vampire can resist Akasha on their own so they spend most of their energy trying to talk her out of reducing the male population by ninety-percent and assuming autocratic control over the globe. No film studio at the time was going to portray a supervillain that specifically targets men.

What gets lost in translation are the moral stakes. When Lestat wakes up in the twentieth century, he is delighted by the rise of secular humanism and at least some progress being made in gender equality. Those were things he never would have anticipated happening during his human lifetime. He saw humanity begin- however awkwardly -to graduate from the world he once took for granted. This theme reappears when he finds Marius, who believes that the Enlightenment was the greastest step forward the west had taken thus far.

Confronting Akasha was the first time that we got to see this optimism challenged. Marius had some of his most glorious lines in that battle. To paraphrase: humanity has fucked up a lot in both the ancient and modern world. But look at the new ground that was broken in the twentieth century. Do we really want to take humanity’s destiny from them just as they’re starting to peck out of the shell?

The dignity of humanity versus the belief that humans are stupid and helpless and need a stern parent to keep them in line. Yes it’s a debate. Yes a debate is people talking. But it was one of the best scenes Anne Rice ever wrote. No it is not Helm’s Deep but it is a climactic fantasy battle.

The comic keeps it concise: most of the lines are spoken by Akasha, Maharet and Marius. Objectively, you can’t complain. I missed Louis’s appearance, though. In the book he is silent for most of the debate and then butts in assertively. Louis was the weakest vampire present and Lestat was shitting bricks because he thought Akasha was going to incinerate him on principle. Akasha herself appreciates his bravery even if she’s not convinced by him.

That’s my one note for the ending and I guess its more of a nitpick. Otherwise: wonderful comic

On issue 12: