Big spoiler warning for the musical Lazarus

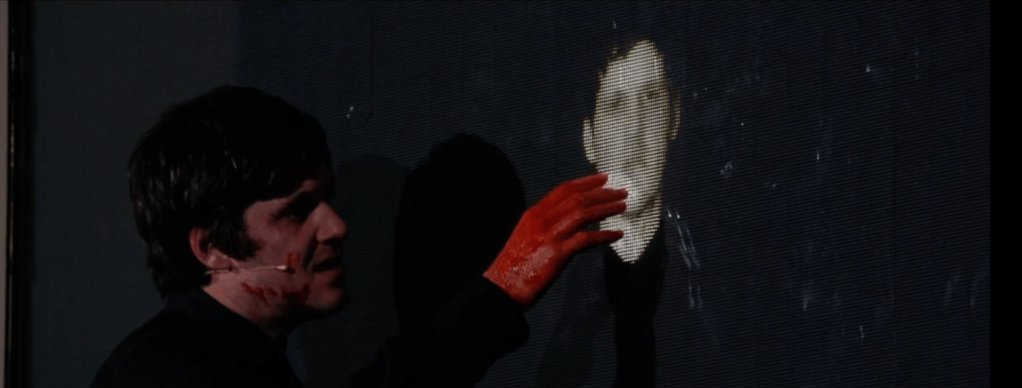

The 1976 Nicolas Roeg film The Man Who Fell To Earth is chiefly about visions. Newton’s home world saw the abundance of water on Earth through their own variation of TV. Newton can see light spectra that humans cannot, like x-rays. There are scenes where Newton looks into the past of places on Earth and is seen in return. Newton also had an uncanny connection to the three humans he was to have the most involvement with before meeting them (Oliver Farnsworth, Nathan Bryce and Mary Lou).

Events like these suggest that Newton can see across dimensions as well. Many of his decisions (such as when to sell patents and begin constructing a space craft) are dictated by his visions.

In addition to this, there is a passive thematic emphasis on eyes. After the true shape and color of Thomas Jerome Newton’s eyes are revealed, we are shown Mary Lou in a room with an oil painting of a cat. The shot begins with a close up of the cat’s golden eyes with their vertical pupils. In conjunction with Newton’s extra-dimensional vision, the close up of the cat painting makes an understated connection with the eyes of a cat. To say nothing, of course, of the wavelengths of light that cats can see but humans cannot (or the resemblance between Newton’s eyes and cat eyes).

I have not yet read the original Walter Tevis novel that inspired both the film and the musical. From the research I’ve done so far, though, there is no indication that Thomas Jerome Newton was able to see across time in the book. This appears to have been the biggest point of departure for the Nicolas Roeg film and Bowie’s musical.

In the 1976 film, Newton decides to build his house at a spot where he makes brief contact with early American settlers. Another vision of one of his kind ascending from a lake toward the sky prompts him to sell all of his patents and begin work on the space craft. The reality of these visions is even validated by others, such as Oliver Farnsworth going to the site of Newton’s landing on Earth moments before it happened. Others have an uncanny awareness of Newton as much as Newton is uncannily aware of other things.

With so much investment in real visions, Newton’s obsessions with alcohol and television resemble misguided logic. Visions or prophecy are conceptually similar to remote viewing. It makes sense that Newton would investigate other means of “seeing things” that are not present in front of him. The logic would be similar to that of a psychonaut who knows they have seen something real and is trying to see more through experimentation. Newton is also a foreigner to Earth, so it makes sense for him to be blindsided by alcohol and (local human) television.

Roeg’s film and Bowie’s musical tell stories that turn on visions. In particular, the importance of true visions and the danger of false visions.

The musical called Lazarus is a continuation of the Roeg film. The fact that David Bowie took the initiative in 2013 to solicit Enda Walsh to co-write this project begs certain questions. It would not have made sense for Bowie to feel entitled to the novel that Walter Tevis wrote. But it would be understandable if Bowie felt a sense of possession or belonging with the 1976 movie that he starred in.

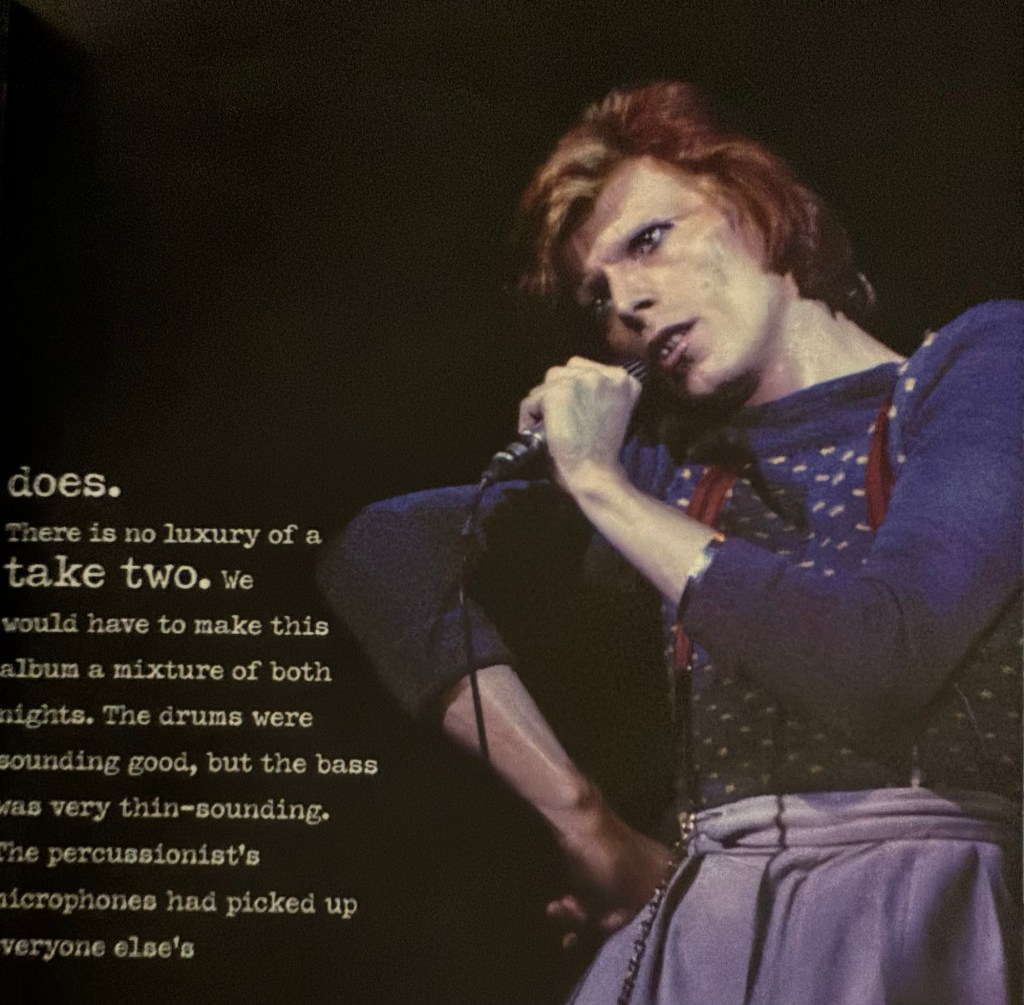

Another essential factor was Bowie’s love of storytelling and creative experimentation. He wrote the lyrics for 1974’s Diamond Dogs using a variation of the cut-up and fold-in technique pioneered by William S. Burroughs. Around the time Diamond Dogs was released, Rolling Stone printed a conversation between Bowie and Burroughs. Decades later, Bowie used the cut-up and fold-in method of generating ideas for the 1.Outside album.

Most famously, though: David Bowie broke ground with his use of fictional characters. Ziggy Stardust was a character that Bowie took onstage and into interviews. A fan base became attached to Ziggy and, immediately before Diamond Dogs, something had to give. Bowie had become almost debilitatingly attached to embodying Ziggy which- combined with the character’s popularity -quickly began to be suffocating. The concert recording called Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars: The Motion Picture captured the very last concert with Ziggy.

After that fateful 1973 Odeon Hammersmith performance, many of his characters were handled differently. Halloween Jack from Diamond Dogs was little more than a change of clothing and a line in one song. The Thin White Duke was the next strong, distinct personality but the Duke’s volatility made him unwieldy. 1.Outside featured six named characters against a cyberpunk backdrop. Bowie said at that time that multiple simultaneous characters were less of a psychological risk. Ziggy, as a solitary presence, once threatened to overwhelm him. The large cast of 1.Outside divided the energy and thereby allowed Bowie to come and go from their world as it suited him.

And then there are the ways in which Bowie’s most famous persona would have effected the expectations of those seeing the movie at the time it was released. Ziggy was an alien that humans make first contact with in the final five years of their existence. He is deified to disastrous effect. Thomas Jerome Newton is an alien that comes to Earth in the hopes of using its resources to save his home world. Both are aliens who meet their fate on Earth. Both stories have apocalyptic stakes. An argument could be made that Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs chronicle the final era of Earth’s history. The events of the final five years, perhaps.

Bowie’s presence alone would have been a reason why many would go and at least “check it out.” It may have been obtuse for anyone to say so out loud, but a lot of those early viewers probably felt like they were watching David Bowie: The Movie. While Ziggy may have primed audience expectations, the character invented by Tevis bore a similar name to another Bowie persona: Major Tom. Like Mary Lou’s Tommy, Major Tom also left his planet and became stranded.

Here, we hit upon one of the differences between the 1976 The Man Who Fell To Earth and Lazarus. In both stories, Tommy is an alien attempting to co-exist with humanity. In the 1976 film, he has just arrived and is figuring everything out the hard way. He has a clear emotional and ethical frame of reference from his home world and he expresses this, in human terms, more than once. Sometimes, Tommy speaks over the heads of his human companions and collaborators…other times, he speaks plainly and the human characters still feel blindsided.

In one exchange with Farnsworth and Bryce, marriage and children come up. Newton is surprised to hear that Bryce has a family but rarely sees them. His reaction is quiet but it is also plainly emotional: “A man should spend time with his family.” Concern for family is, of course, the whole reason why he is on Earth.

In another conversation, he hears that the secrecy surrounding his private engineering projects has given rise to speculation that he is building weapons. He sputters, incredulously, wondering why they immediately “assume it’s a weapon.”

In The Man Who Fell To Earth, these feelings and boundaries are intact and Newton is hyper-aware of how foreign Earth is to him. Lots of things upset and agitate him and he insulates himself whenever possible.

By the end of the movie, Newton has been abducted by humans, had his lenses fused to his eyeballs by human experiments and loses any chance of seeing his family again.

In Lazarus, Newton has spent decades being wounded and entrenched. His nerves have been fried and cauterized and he exists, seemingly, only for gin, Twinkies and Lucky Charms. Only his self-isolation has stayed the same: as far as he’s concerned, humans have proven themselves dangerous.

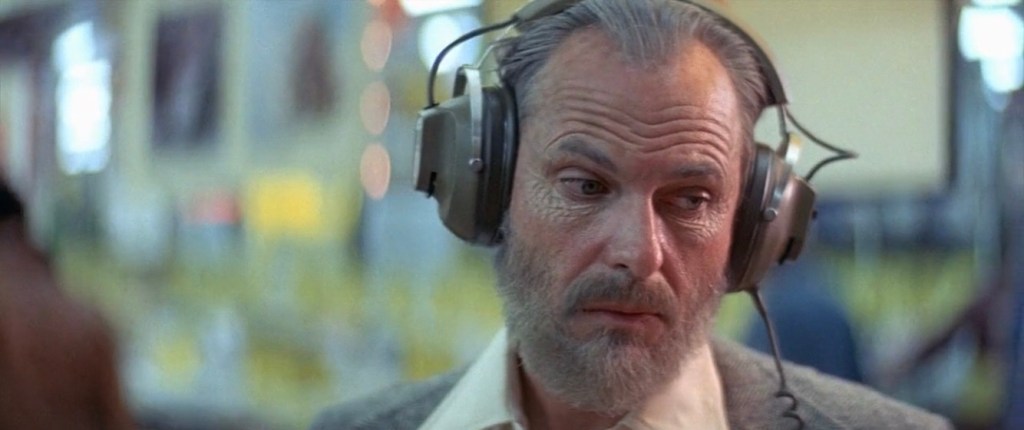

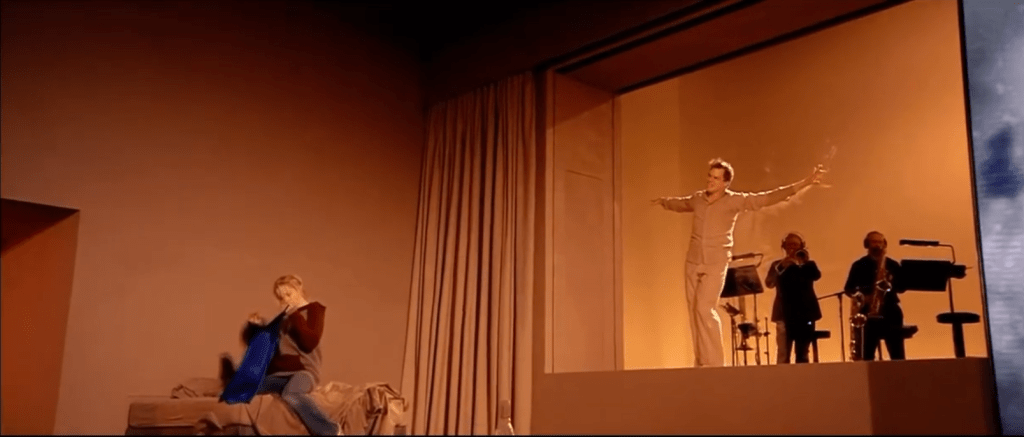

The structure of Lazarus, predictably, contrasts inside against outside. Newton’s solitary life includes two other people: a personal assistant called Elly and a man called Michael, who appears to have a personal or professional connection with Newton. Michael’s portrayal in the Danish Aarhus production is very reminiscent of Bryce, as acted by Rip Torn in the ‘76 film (particularly with Rip Torn’s hair and makeup in the film’s final scene). Elly’s unhappy domestic life with her partner Zach forms a bridge between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’.

Michael, singing ‘The Man Who Sold The World’, played by Bjørn Fjæstad in a 2019 Tel Aviv performance at the Enav Culture Center. This performance also shares a lot with the then-contemporary Aarhus production. Part of the same run? Newton was played by a different person, though- an Israeli singer professionally known, simply, as Adam.

On the opposing ‘outside’ half, the central character is simply known as The Girl- later referred to as Marley. Marley and Newton are our leads but their awareness of each other is often private.

The narrative constantly teases a mysterious parity between Newton and Marley. I suspect this is because Marley is “seeing” Newton just like Newton “saw” the three main human characters of the ‘76 movie before meeting them (Bryce, Farnsworth and Mary Lou). As with Newton, Marley’s sight goes two ways. While she sees Newton, Newton also sees her.

This could make Marley a 4D telepath like Newton…or maybe even a survivor from Newton’s planet. Marley has the same analytical, itemizing ear for human language that Newton had in his early years on Earth: “I’m supposed to help you in some way.”

“Well, you can help me find another Twinkie.”

“I think it’s supposed to be ‘help’ in the caring sense of the word, Mr. Newton.”

“Oh…like a…very small nurse…?”

It’s interesting here that Newton now sounds as obtuse as Farnsworth, Bryce and Mary Lou once sounded to him, back in the seventies.

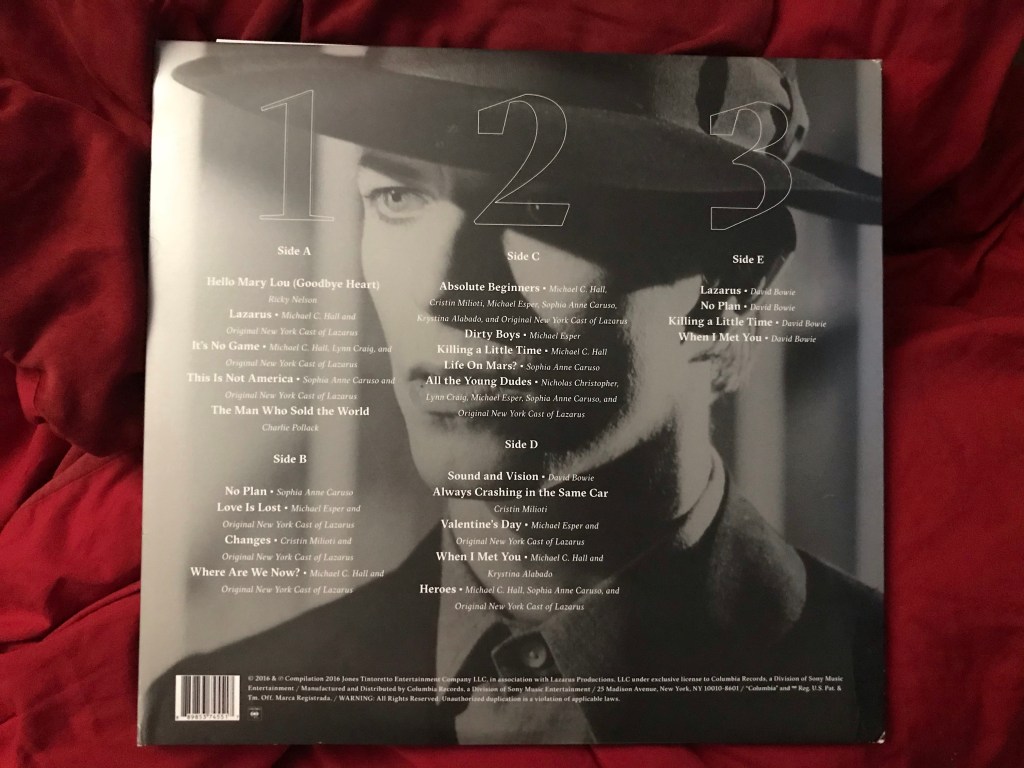

I’m taking the time to hammer out these details because recordings and reference materials are hard to come by. Synopses are common but not very useful. The official cast recording tells us which actor sings what and which character they represent. While I would have loved to have seen the show in person, not everything can run everywhere. Adam, from the 2019 Israeli performance, appears to have uploaded video of most the musical numbers on YouTube, relative to other channels. The best I could scrounge up was a full-length audio recording of the show, with dialogue, incidental audio cues and the rare audience noise here and there. Eventually, I was lucky enough to see the whole thing.

Many of the scene transitions have a pastiche feel to them. The spectre of bare-assed abstraction is kept at bay by frequent simultaneity of character arcs.

Marley’s first appearance (represented in the first theatrical run and the cast album by Sophia Anne Caruso) resembles a haunting. Newton flinches and cringes around her and she never makes eye-contact with him, even if her hand ocassionally flails in his direction and touches him. Once, she dives into Newton’s arms, but it is not at all obvious who or what she is cuddling on “her end”. The whole time, she is singing ‘This Is Not America’, and its one of my favorite performances from the cast recording.

Newton, having fallen for multiple false visions already, does not take this experience at face value. We are, evidently, following Marley’s visionary/astral travels as she wanders into the home of Michael, who has discovered a separate, non-astral traveler in his apartment.

Marley’s travels, words and observations, from the latter half of her first Newton visit to her sighting of Michael and the stranger, are represented in the song ‘No Plan’. At this point in the story, ‘No Plan’ sounds like an answer to ‘Lazarus’. In ‘No Plan’, Marley is very much aware of her psychic abstraction and potential vulnerability. If ‘Lazarus’ is another timeless moment, than Newton starts the play abstracted beside past and present versions of himself and xeroxed fragments of loved ones. Marley, in her timeless state, knows everything about Newton and nothing about herself. Newton and Marley see the wilderness of time from opposite perspectives.

This prompted me to re-examine other uses of apparent simultaneity and pastiche, like ‘It’s No Game’ and ‘Absolute Beginners’. In each of those pastishes in which Newton is included, he may be ‘seeing’ the other characters through time and space. It becomes possible that Newton may even be aware of the events of musical numbers from which he is excluded- coming through, perhaps, as white noise in the background of his mind.

The ’76 film began with Newton making psychic contact, through time, with Oliver Farnsworth, Nathan Bryce and Mary Lou. What about Lazarus? Newton and Marley see each other. Elly and Michael know Newton personally, so they’re out of the running. What about the person Michael ran into in his apartment, with Marley watching? An apparent stranger, who only crosses paths with Newton later on? The prophetic trio in Lazarus could be Newton himself, Marley and Valentine the stranger.

Yes, the whole prophetic-psychic contact thing is just my interpretation. There are supportive patterns, though. Much of Lazarus’s simultaneity begins to make sense when seen as visionary experiences across time. The reason it can’t be something more generalized is because there are degrees of awareness between the characters. A character could be visible to others, occasionally visible or invisible in the manner of a ghost or a witness from a psychic distance.

Newton’s mention of his visions also happen at narratively significant moments. He talks about them for the first time with Michael, before singing ‘Lazarus’. After this point, Newton will describe Marley to other people like Elly as something that’s probably not real. Slowly, his opinion changes. The next time he makes specific reference to his visions is near the end, in conversation with Valentine. He asks him if he killed Michael. When Valentine asks where the question came from, Newton says “I see things.”

Along with the placement of those two scenes, there’s the stage direction of the original run. Before the play started, Michael C. Hall (Newton) would be lying still on the stage. The actual beginning manifests around him. This, to my eyes, is a subtle echo of the scenes in which Newton can perceive things but not interact with them. That barrier alone implies that something is happening with Newton’s visions.

These associations and blind spots relate to specific relationships…yet other things take place beside and between them.

Newton and Marley are characters who can see things across time. Those who they can see can also see them (our two main characters, Elly and Valentine- even if those last two gain and lose awareness of Marley).

There are three other characters, though, who are able to approach and interact with anyone: the Teenage Girls. Many reviews equate them with a Greek chorus which is fair: they are almost always present and, when not interacting with other characters, they look and sound like the kind of everyperson / audience surrogate that backup singers normally portray in musicals. While they only take charge of the foreground twice, those are two of the most pivotal moments in the story.

In the first instance, Marley harries Newton into watching a reenactment of his last conversation with Mary Lou. Why? For “therapy”. She waltzes into his apartment followed by the Teenage Girls, one of whom walks up to Newton and apologizes in advance for any mistakes she might make portraying him. Newton corrects the Teenage Girl when she misremembers a line and then Marley (portraying Mary Lou) begins to address Newton himself in the reenactment: “You’ll be stuck in this apartment with me and I’ll always know you didn’t want to stay. Not with me you don’t. Nor for me, Tommy.”

At this point, Newton gets overwhelmed and walks out of the whole thing. Marley follows him and he asks her to tell him something only he would know. This appears to be a search for validation: to determine if Marley actually knows what she’s talking about or if this is some elaborate and sadistic manipulation. To his dismay, she relates his private memory of taking walks with his daughter on his home planet. They would rest on a hill, where he would tell his daughter stories about space, which he made up on the spot. When he was about to trail off, his daughter would tell him to “speak some more”.

Newton deflates under the realization that Marley is a genuine psychic outsider. He is on the verge of turning inward again when Marley says “(y)ou knew you’d end up like this. That’s why you let Mary Lou go. You don’t have to stay here any longer, Mr. Newton.”

As Newton absorbs the bald reality of these words, we transition to the song ‘Absolute Beginners’. Here I gotta admit to being a bad Bowie fan: ‘Absolute Beginners’ never grabbed me. Yes, the sixties song-styling is a contrivance; the problem is that it sounds contrived. I never liked the song until I heard the version from Lazarus…and the Lazarus version is stunning. As far as I’m concerned, the Lazarus renditions of ‘This Is Not America’ and ‘Absolute Beginners’ are definitive (not to mention ear-worms).

There are a few narratively significant details about this scene. There’s more simultaneity, what with Marley and Newton singing to each other while Valentine sings backup and Elly sings the second verse. Perhaps most importantly, though- Newton commits to Marley’s plan to rescue him from Earth near the end of the song.

The Teenage Girls are also usually the most active in the songs sung by Elly and Valentine. While Newton does not have 4D visions of Elly, Marley does. Both of them have 4D visions of Valentine. The strongest argument for the Teenage Girls as “neutrals” would be the ‘All The Young Dudes’ scene, where Ben and Maemi sing lead. Even this scene has Elly and Valentine, though- they’re just being constantly ignored by Ben and Maemi. Valentine, being his usual manic and easily offended self, corners Ben and Maemi in the bathroom with Marley in tow. Things move fast from here.

A brief clip of Bowie’s original ‘Sound and Vision’ recording plays while Valentine stabs Ben and Maemi to death while Elly cringes in the opposite corner of the bathroom, holding still enough to blend into the scenery. After Valentine flees the scene, the lighting changes and Elly slowly rises to her feet, singing ‘Always Crashing in the Same Car’. This is one of the most beautiful song transitions in the whole play, especially as portrayed in the original New York production. Elly is as still as a statue and, once she’s alone, her first movements are when she sings “(e)very chance, every chance that I take” as she stands up.

‘Always Crashing in the Same Car’ is one of the show’s most powerful moments in both versions I was able to find (New York and Denmark/Israel) but the next song, ‘Valentine’s Day’, is a definite win for the New York production.

I could go on about the differences between the productions. The Denmark/Israel show appears more invested in Newton building a literal rocket. The inclusion of Newton as an active participant in the ‘All The Young Dudes’ scene creates the impression that it’s taking place in Newton’s apartment. The only reason I can imagine for Ben and Newton to know each other would be if Ben is either a wealthy engineer or a wealthy tech investor who is helping build the rocket. This would also mean that the rocket drawing on the floor of the stage is non-literal. In the New York production, the rocket drawing is just a drawing on the floor. The New York version also takes pains to emphasize that Valentine and Elly followed Ben and Maemi to a random nightclub. Newton is not present- just “seeing” events unfold from a distance.

While we’re talking about Valentine, his contrast to Newton and Marley is striking: the stage direction and the behavior of the actors in the New York performance establish that the 4D visions are a major plot device. As surely as Marley and Newton’s visions are real, Valentine’s instincts are all wrong. He slides quickly into hero-worship, during which he’ll vocalize delusional memories of things that never happened, such as Michael coming out as gay and being rejected. Valentine also has virtually no boundaries which makes it very easy for him to fall in love and lust. Give him some rejection, though, and the momentum swings in the other direction. This is usually what happens just before he kills someone.

As he sings ‘Valentine’s Day’, black balloons drop from overhead. The Teenage Girls rush onstage and start popping them, leaving only one which Valentine uses as a prop in the next dialogue scene. Near the end, they start doing their usual backup singer thing with the “yeah”s and “Valentine, Valentine”s. The Teenage Girls are also very active when Valentine sings ‘Love Is Lost’ and Elly’s performance of ‘Changes’.

Then, well…there’s the ending. This is the second instance of the Teenage Girls entering the foreground. Or, more accurately, a Teenage Girl. She is usually listed as Teenage Girl 1 and she puts her hands on Newton- with Valentine -in an attempt to make him stab Marley. This is also the first time we see Valentine and Marley interact with one another. As this is happening, Newton and Teenage Girl 1 are singing ‘When I Met You’.

Marley only begins to recover memories in the final scene, when Valentine enters Newton’s apartment.

Marley: “I was alive once. I was a real girl.”

Valentine: “And what else?”

Marley: “I was cut down a mile from my house and buried in the ground. And not properly dead- I was lying there. My eyes closed. With no real future(…)I’m sorry…but it’s not me who’s going to get you to the stars but it’s you who will help me die properly.”

When was the last time the Teenage Girls took charge of a scene? Just before ‘Absolute Beginners’ when Newton finally agreed to cooperate with Marley’s idea for conjuring a psycho-ceremonial spaceship. Marley, Newton and the Teenage Girls participated in a reenactment. Perhaps the scene with Valentine, Marley, Newton and Teenage Girl 1 is also a reenactment. It seems significant that Marley began recovering memories once Valentine showed up.

Before this point, I was attached to the interpretation that Marley is Newton’s daughter, since the continuity only prepares us to expect Newton’s species to have the 4D visions. What happened to Newton’s planet, though? Presumably it died out, after Newton failed to convey water there in the seventies. His daughter may have been ‘cut down’ in such an event but that doesn’t seem likely. Let us not forget the serial killer with a preference for blades.

As Newton only comes around after the prior reenactment, Marley only remembers her name after this one. I’m not going to say that Marley was canonically Valentine’s first victim but it sure looks like it. Her apparent age may be significant to- she could have been of an age with Valentine. Perhaps he killed her when they were in high school together. This would give significance to some of the lyrics in ‘Valentine’s Day’ (a song about a fictional school shooter that Bowie originally wrote for the album The Next Day, around 2012-2013).

The transformation after ‘When I Met You’ is even more dramatic than the ‘Absolute Beginners’ transformation but I’m not going to get into that just now. I’m still not altogether sure how to interpret the very last story beats and the very last musical number.

Remeber when I first mentioned that the ’76 film started with psychic contact with Farnsworth, Bryce and Mary Lou? I don’t think my first idea about a Lazarus triad was wrong so much as incomplete. Marley and Newton see each other and both of them see Valentine. Distinct from Newton, Marley could be said to have her other own set of three: Newton, Valentine and Elly. Since I saw the Denmark/Israel footage first, I briefly entertained the idea that Newton also had a distinct set of three: Marley, Valentine and Ben, what with him helping to build an actual rocket.

I am tempted to treat the New York production as canonical, though, since it was the version that had the most input from Bowie just before his death. While Marley seems to have her own unique set of three, the set shared by herself and Newton looms larger.

What was the deal with the ’76 triad, again? Two of them were directly explicable: Farnsworth the patent lawyer and Bryce the engineer. Mary Lou was a wild card. In Lazarus, Marley and Newton are the first two and they’re explicable because they glimpsed each other across time. Valentine is then the obvious wild card. Then there’s the three Teenage Girls who are the only characters capable of interacting with everyone else. One of those Teenage Girls helps Valentine attack Newton and Marley, almost as if she’s the influence behind the ‘wild card’ phenomenon.

This external influence would have been present behind Mary Lou, in that case. Consider how this informs our earliest diegetic glimpse of Mary Lou- a suitcase of her clothes under Newton’s bed, first seen when Newton sang ‘Lazarus’. Later, when Elly discovers this, she assures Newton that he has the right to “play dress-up” in the privacy of his own home.

This could be a throwaway gag…but this brief moment of equating Newton with the owner of the clothes echoes something else. Whenever Newton tells Marley that she’s a hallucination, he finds he is addressing a very confused Elly. Elly later wears the clothes in a ham-fisted and aggressive attempt at seduction. And then the play’s last major plot shift may include some metaphysical force that brought Mary Lou to him in the first place.

The multiple instances of taking and replacing the case of clothes under the bed reminds me of the music video for ‘Look Back in Anger’. The song accompanies a narrative of Bowie painting a picture of an angel. The more he adds, the more his own flesh gets sapped.

The last image of the video is Bowie crawling under a bed. Perhaps that association is superficial. Either way, I thought of the ‘Look Back in Anger’ video every time someone pulled out or put back the clothing. All of these clothing-related *ahem* layers are potentially affected by the nature of the force that sings ‘When I Met You’ with Newton.

I could keep going about the possible interpretive layers. Lazarus is a beautiful show that is worth seeing, either through video or theater. Lazarus is worth analyzing in depth but this is not where our buck stops. I went over it in all this detail because Lazarus is the story that provided David Bowie with the point of departure for his very last album: Blackstar.

When I first heard Blackstar, it left me with a sinking feeling. Yes, David Bowie had just died and that was a factor…but it was also the album.

Early on, there are two songs that luxuriate in the amount of space they take up: the ‘Blackstar’ title track and a re-recording of ‘Lazarus’. Those are also, to me, the two most lyically ambitious songs on the commercial release of Blackstar. Neither of those songs are in a hurry, either. ‘ ‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore’ bridges the gap between track one (‘Blackstar’) and three (‘Lazarus’). It is musically energetic and the lyrics seem (to me) less ambitious and more like a vehicle for Bowie’s voice to fit in with the instrumentation (John Ford literary reference notwithstanding). ‘ ‘Tis a Pity She Was a Whore’ was initially released in November of 2014, just after Bowie had finished working with the jazz band leader and composer Maria Schneider, with whom he created the original version of ‘Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)’.

All of the songs with the looser, more stream-of-consciousness lyricism sound as if they could have evolved from the Schneider collaboration. A lot of the jazz influence is crystal clear even if Blackstar dressed things up with a crunchy drum-and-bass emphasis. The blend of the two creates a cyberpunk effect. The Blackstar version of ‘Sue’ (track four, after ‘Lazarus’) sounds like a slice of life from the version of LA that Ridley Scott created in Blade Runner. The original 2014 version, with its accoustic jazz emphasis, evokes Cowboy Bebop.

‘Sue’ is the turning point of the album. Only three songs remain: ‘Girl Loves Me’, ‘Dollar Days’ and ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’. These songs are, pretty much, no longer or shorter than most of the album (well…except the title track and ‘Lazarus’). The emotional sketches become even more stark, though, which could create the impression that they are somehow shorter.

‘Girl Loves Me’ is playful and irreverent with dark images and implications creeping into the margins. Bowie sings “I’m sitting in the Chestnut Tree”. This refers to a location from Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four (which provided inspiration for Bowie’s Diamond Dogs album): a bar where the victims of the Ministry of Love congregate. Each of these listless, aging people have experienced the psychological torture and brainwashing culminating in Room 101: a staged confrontation with a personal fear, calculated to make you renounce all ties except Big Brother.

Eventually, both Orwell’s protagonist Winston and his love interest Julia end up getting cracked in Room 101 and both linger at the Chestnut Tree later on. In the Chestnut Tree, everyone knows what they have in common but they never discuss it. Slang from Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange is used; another near-future story about brainwashing.

These shadows are there in the margins while the music has a quality that I can only describe as playfully swerving. Sort of drunk and mischievious but on the brink of trailing off. Happily drunk at eleven in the morning, not long before the depression rebound at noon.

Things get dark with the song ‘Dollar Days’. This…is hard for me to put into words but I’ll try. It has a longing quality that upsets me. It worms its way into my head when I’m suddenly hit the reality that I’ve lost someone and I’ll never see them again. And I’m not just talking about Bowie. Recent griefs, in the last few years, were made worse for me by this song not leaving me the fuck alone.

‘Blackstar’ and ‘Lazarus’ are like the delicacies of deep, secure and trusting confidence. An articulation of inner truths that cannot bear to be spoken too loudly. ‘Dollar Days’ is pain that makes you forget you were ever capable of anything as lofty as imagination or understanding.

‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ introduces the positive rebound but it’s an exhausted, relieved positivity. The lyrics are sketches of moments like the last two songs but things still get pretty lucid…maybe more lucid than I would like: “(s)eeing more and feeling less / saying no and meaning yes / this is all I ever meant / this is the message I have sent”. No, we’re not in the same pit of sadness as ‘Dollar Days’ but the notes of relief…well…they complicate things. And the relief is palpable. There’s a harmonica part in the beginning, as in ‘A New Career In A New Town’ from Low, and the chilled out, free-roaming vibe is similar. In a beginning-to-end listening, ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ leaves one of the more complicated impressions.

Some disclaimers before moving on: this is the version of Blackstar that Bowie released into the world. The worst thing I can say about Blackstar is that it’s emotionally challenging- and this is not a weakness. Art is allowed to be somber. Perhaps its the nature of that emotional complexity that makes me feel things like: “This is a little much…can’t we take a few steps back?”

Sometimes the anwer is no.

If Blackstar is a dark album, it is entitled to remain one.

I encountered a separate version, though.

Yes it’s a bootleg and yes it came out after Bowie died. 2017, to be exact. This is a cassette tape made of clear, glittery plastic, labeled ‘SPECIAL EXTENDED LIMITED EDITION 2017’ on the cover. On the back of the case, there is the star image from the Alexander Hamilton musical. It was distributed from an Italian source and it cannot be traded on Discogs. On the Discogs website, they say they only refuse to support trading items due to objectionable content or copyright violation. Unless Blackstar is shockingly offensive to someone, I suspect we’re looking at the latter.

This cassette tape differs from the commercial release of Blackstar in two ways: the three other songs Bowie wrote for Lazarus are inserted between ‘Girl Loves Me’ and ‘Dollar Days’ and it closes with the original, jazz-centric version of ‘Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)’.

The three additional Lazarus songs were rerecorded during the Blackstar sessions and were left off, in the end. Years after Bowie died, they were commercially released on the No Plan EP.

You could pretty much make this playlist with your own music library. If you got Blackstar and the No Plan EP, just plop’em between ‘Girl Loves Me’ and ‘Dollar Days’. Maybe throw the original ‘Sue’ onto the end, if you feel like it. That last part is the most negligible. I like the original ‘Sue’ but putting it at the end like that feels like a pallette cleanser. It’s nice but obviously unnecessary. Sometimes it can hit like a reply to the earlier ‘Sue’ which is neat. The three other songs and their placement change the whole flow of the album, though.

Before I saw Lazarus, I felt that Blackstar relied on the associative impressions between songs. Each one is self-sufficient but each one also has a linear association with the music before and after. It starts with a glimpse of the beyond, goes back to ordinary life and then another glimpse; shorter than the last. The narration goes through a grieving cycle in the absence of a third.

Before the playful ‘Girl Loves Me’ can transition to the sad-drunk ‘Dollar Days’, a third introspective beat occurs with ‘No Plan’. Since I had years of listening to the commercial Blackstar beforehand, I had long thought of it as an album “narrated” by one perspective. It is comparable to an experimental film with one character in either one or two locations. Not only does ‘No Plan’ provide another introspective beat to go with ‘Blackstar’ and ‘Lazarus’ but it almost feels like a scene change. Maybe a cut to a second person. Yes, that’s the job it does in the musical: Newton sends out a beacon with ‘Lazarus’ and Marley pings back with ‘No Plan’. But the transition from ‘Girl Loves Me’ on the 2017 Italian bootleg is so different that it creates the same effect: a new place, a new person or a new development from the original protagonist.

After I saw Lazarus, there was something about the structure that stayed with me. The play alternates dialogue skits with musical numbers. This surprised me, since Bowie has said in the past that he prefers musicals that are sung-through: meaning no conventional dialogue. One hundred percent of it occurs through music. In a 2021 Rolling Stone interview, Lazarus director Ivo Van Hove said that the music was meant to integrate with the spoken dialogue. Songs like ‘Absolute Beginners’ involves Newton and Marley and the scene they share. Yet it also involves Elly and Valentine, who are not present. As Valentine sings ‘Love Is Lost’, Ben and Maemi are dancing in colorful film projections.

In other words: every song is “spoken”- even the ones with only a single character. When Newton sings ‘Lazarus’, he is convinced he’s alone and is surprised to find that he isn’t. Even Marley seems a little abstracted when she first appears- slowly becoming aware of Newton as she sings ‘This Is Not America’. I know I said ‘No Plan’ was like Marley’s answer to ‘Lazarus’- and it is -but it’s a delayed answer. She’s half-alone, like Newton. As Newton was surprised to find Marley listening, Marley is surprised by the apparitions of Newton, Michael and Valentine. All you gotta do to create infinite layers of who is adressing who is to introduce 4D telepathy as a plot device. It’s also an easy device with which to introduce the simultaneity of character arcs- as if to be psychic is to hear everything, all the time, even if it mostly sounds like static.

Lazarus relies on an AB rhythm with its music and scene transitions. Blackstar has something similar going on, although it’s back-and-forth reciprocity only holds through the first four songs. The rest of the album from that point takes place while waiting for a third encounter that never happens.

The addition of ‘No Plan’, ‘Killing A Little Time’ and ‘When I Met You’ struck me as a return to the AB rhythm. It could just as easily be the other side of the wall, though. More specifically- if the narrator is left hanging from ‘Girl Loves Me’ to ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’, then maybe ‘No Plan’ to ‘When I Met You’ is the other side of the isolation. The other person who is left hanging.

More superficially, it’s just comforting hearing the lyrical excess of ‘No Plan’ through ‘When I Met You’ because so much of Blackstar is tense and withdrawn. It evens out the album’s rhythm but it also changes it deeply. The gut-punch of ‘Girl Loves Me’ through ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’ is robbed of its urgency.

What makes the original Blackstar so tense is that the angst is a creeping intuition. One effect of the three song addition is giving specific voice to the angst with the song ‘Killing A Little Time’.

‘When I Met You’ is neither the first time Valentine has been in Newton’s apartment nor the first time the two have met. Earlier in the play, a subplot develops around a relationship between Elly and Valentine. When they first meet, Valentine convinces Elly to introduce him to Newton. When they meet, both Valentine and Elly start peppering Newton with questions about the drawing on the floor (“I drew something awful on it” as the feller says) and his mental health. Newton’s last encounter with human medical attention ended with the worst trauma of his life so he bristles, leading us into ‘Killing A Little Time’.

In the original Blackstar album, the narrator’s suffering is very reactive. The anger of ‘Killing A Little Time’ allows him to claim ownership of his pain which makes the end easier to bear. The more I think about this, though, the more I wonder if there are other factors.

The most obvious theme shared by both Lazarus and Blackstar is sacrifice. Blackstar discusses this in more emotional terms but both works touch on ceremonial sacrifice. The ‘Blackstar’ music video shows the corpse of an astronaut falling toward a planet. It is found by a girl with a tail who discovers, once she looks inside the helmet, that the skull is encrusted in jewels. Either the skeleton was venerated where it lay at one time or it just “is” what it is. Either way, she brings the skull to a village where a religious awakening happens. According to the lyrics “(s)omething happened on the day he died / spirit rose a meter then stepped aside / somebody else took his place and bravely cried / ‘I’m a Blackstar’/ how many times does an angel fall / how many people lie instead of talking tall / he trod on sacred ground he cried aloud into the crowd/ ‘I’m a Blackstar'”

The logic of ceremonial sacrifice is apparent: something is sent across in exchange for something else. In ‘Blackstar’, the mystery behind the bejewled skeleton creates an opportunity. It cannot speak for itself so others attempt to speak for it. They attempt this with nothing more than boldness and imagination: “I can’t answer why / just go with me”. The words of this person contain an interesting echo: “I’ma take you home / take your passport and shoes”. Usually, you don’t need your passport and shoes if you’re going to one place and staying there. Not to mention: removing your shoes is necessary spiritual grounding for many magical and ceremonial workings. Before the first repetition of the “something happened on the day he died” lines, Bowie sings “I want eagles in my daydreams / diamonds in my eyes”. These could simply be the fantasies of one claiming to fill the void of the corpse but “diamonds in my eyes” sounds like a passive reference to the jewel-covered skull. It furnishes splendid visions but there remains a genuine mystery at work. To want diamonds in your eyes is to commit to something sight-unseen.

Ziggy Stardust, Major Tom and Thomas Jerome Newton have something in common: all three were sacrificed to the outer darkness, never to return. Yes, there is exploratory and visionary abandon and the joy of discovery- all the romantic, escapist bells and whistles. The problem is bringing your discoveries home. In the meantime, how are those behind the sacrifice rewarded? Newton created revolutionary new engineering patents for governments and corporations to sit on and never use. Ziggy started a movement on Earth during the last five years of its existence which turned into just another distraction. If Aladdin Sane and Diamond Dogs cover the aftermath, then things apparently got darker from that point on. Major Tom got his own miserable follow-up in the song ‘Ashes to Ashes’.

With the first two, the fault lies with the beneficiaries of the sacrifice while Major Tom is the author of his own suffering. This is not a unilateral process with a single player, nor is the individual exonerated.

Lazarus pushes a little further, though. Newton is still in “space”, never to return. Is he merely a burnout, like Major Tom? The play does not make him socially enviable. To Elly and Valentine, he is a target of ridicule, larceny and violence. What even happened to him, in the end?

I, at least, like thinking of stuff like that. We know Marley was never physically present at all during the time frame of Lazarus. Valentine would not have left Newton in peace, either. But isn’t Newton immortal?

I think a more accurate term might be ageless. He will never age or experience physical illness. He is not immune to violence, though. In the ’76 film, he is physically traumatized. I can’t think of any reason why Newton would be immune to stabbing. Valentine may well be remembered as an ordinary serial killer, perhaps subject to urban legend: ‘did you ever hear his last victim was a humanoid alien’, etc.

Newton is held in contempt, exploited and murdered. But was he ‘wrong’?

Newton began to hope again after Marley put him through a reenactment. The ‘Absolute Beginners’ number is about him accepting that he has no further obligation to Earth and is free to take Marley seriously. This ultimately leads him to reenact Marley’s murder by Valentine. If Newton didn’t survive, then perhaps he escaped. He arrived on Earth via sacrifice. He only leaves by way of another sacrifice.

Then there’s the role of prophecy. Newton is only given reliable visions in snippets. What are we to make of the big picture? Was his planet meant to die out and was Newton meant to die on Earth, with only another ghost for company?

This is what makes interpreting the song ‘When I Met You’ so hard, whether it’s in Lazarus or Blackstar. At first listen, the song sounds bipolar. Whoever the narrator ‘met’ could be either the best or worst thing ever. They may have been pulled from misery that they took for granted, to relearn what affection and pain are. They either realized how bad things were or everything got worse. And we don’t know which.

The addition of the three songs on the Italian cassette tape makes the build up to the conflicted ending more approachable. The narrator is dwarfed by an unanswerable question in ‘When I Met You’ and then begins the movement through ‘Dollar Days’ to ‘I Can’t Give Everything Away’.

What the three songs offer are the lucidity of an inside view. Should we be so quick to ignore the outside view, though? If the addition of those three songs gives an authorial statement from the ‘inside’, what about the ending of the original Blackstar? We don’t hear the narrator’s internal monologue. With Bowie’s lyrical sketches, it’s more like seeing him than listening to him.

The idea of adding the No Plan EP rerecordings to Blackstar changed the album for me, for awhile. I loved hearing the narrator speak up a bit in the second act. I appreciate what this brings to a relistening but I also realize that Bowie had a beautifully visual mind that we are poorer without.

Here’s a few final thoughts. Don’t worry, it’s short.

https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-features/david-bowie-lazarus-musical-1111847/