Spoiler warning

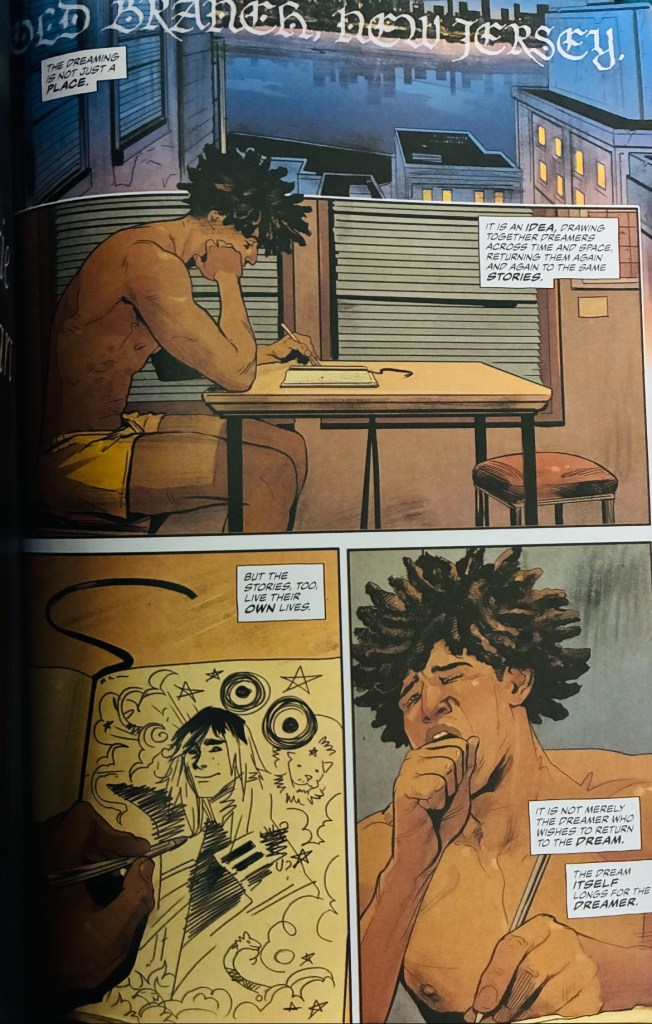

Judging from where things went with Nightmare Country, I wonder if G. Willow Wilson was working on a related concept in ‘Waking Hours’. Volume four of The Dreaming came out roughly at the same time as the first two Sandman Universe Hellblazer arcs and I think all of those were out by the time Nightmare Country ramped up. As Nightmare Country has Madison Flynn and the Corinthian, the fourth book of The Dreaming has Heather After and Ruin. Also like Nightmare Country, the main human and the main nightmare have a dynamic that ropes in other more short-lived events.

A Shakespeare scholar called Lindy Morris dreams something at the wrong place at the wrong time.

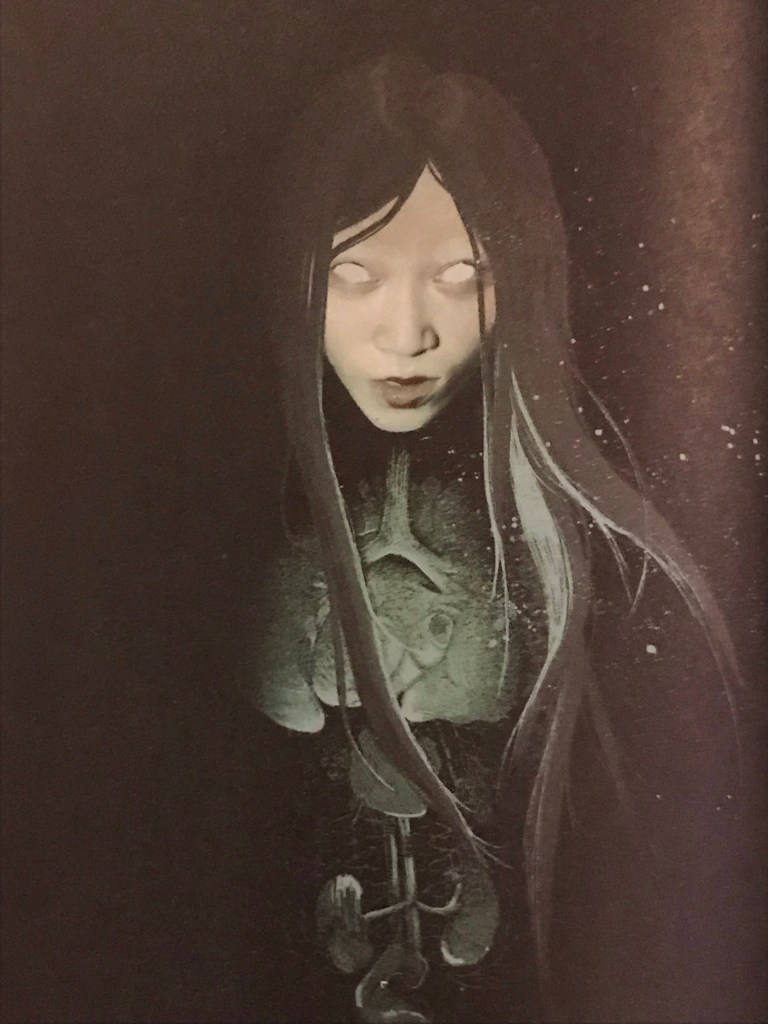

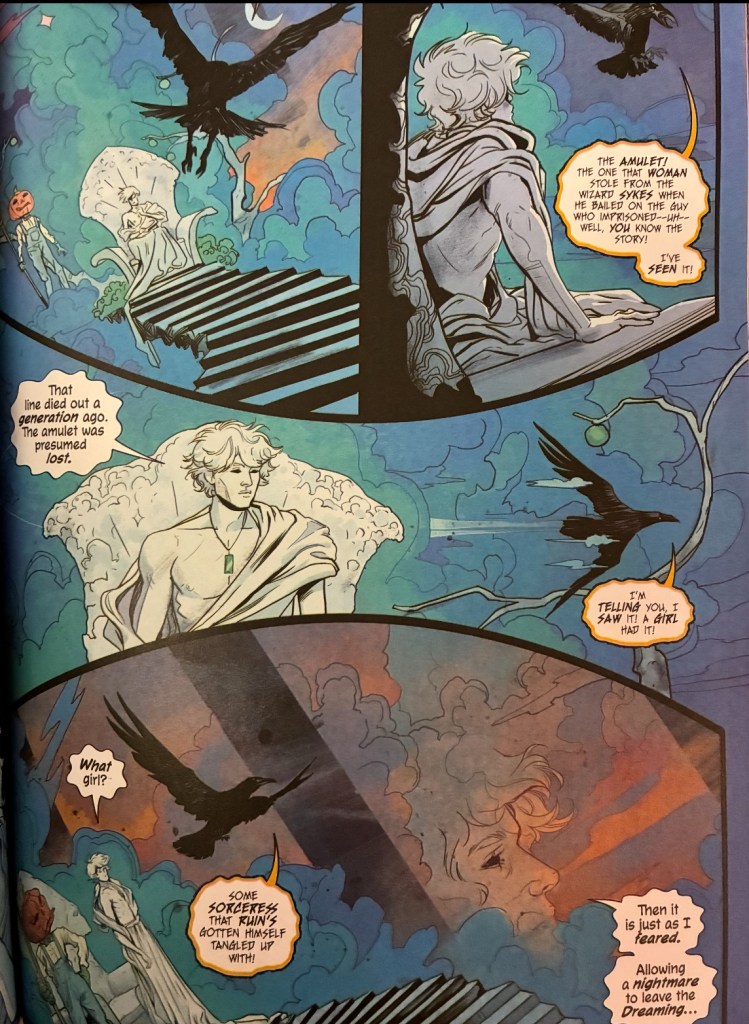

Ruin is a nightmare who escaped from Dream’s quarantine/prison chest with the help of Dora (remember her? The Night-Hag from the first three arcs? She’s now something of a mover-&-shaker at the World’s End inn). Why? Because he fell in love with the first human he tried to hunt on the astral plane. So after escaping, he breaks into the waking world using Lindy’s recurring Shakespeare dreams as an entry point.

Thing is, crossing dimensional boundaries in both a tangible and autonomous state requires serious magical investment. Ruin pulls it off because he accidently shifted Lindy’s tangible body into the world of her recurring dream.

Our main human character, Heather After, is a magician with the mind of puissant gambler; undaunted by the need to put some skin in the game to get things going. She was mentored by John Constantine though, so maybe that’s to be expected (Constantine’s quite the magical educator, isn’t he? First Timothy Hunter then Heather After).

What’s more: she’s handled the transactional nature of sacrifice well in the past. Arguably.

She once attempted a summoning for what she described as a “nice, chill little fire spirit with the intelligence of a goldfish”. Instead she snagged the cherub Jophiel who promptly threatens her in his flaming, lion-headed, multi-winged form. She lets him go when asked and earns a tiny bit of good will.

Around that same time, Jophiel was attempting an astral dialogue with a young Catholic seminarian called Benedict, who had the potential to become the next Pope. Jophiel is channeling various visions and whatnot which- due to Benedict’s human nature -must occur in the theater of dreams. That means that it’s occuring within the Dreaming. Because of this, other dream-kind have enviornomental access which is how Ruin found him and well…you know how Ruin fell in love with his first human victim?

Once Ruin got involved, Jophiel’s intended visions got derailed and Benedict dropped out of seminary. Jophiel is subsequently punished for his failure with temperory banishment to Earth.

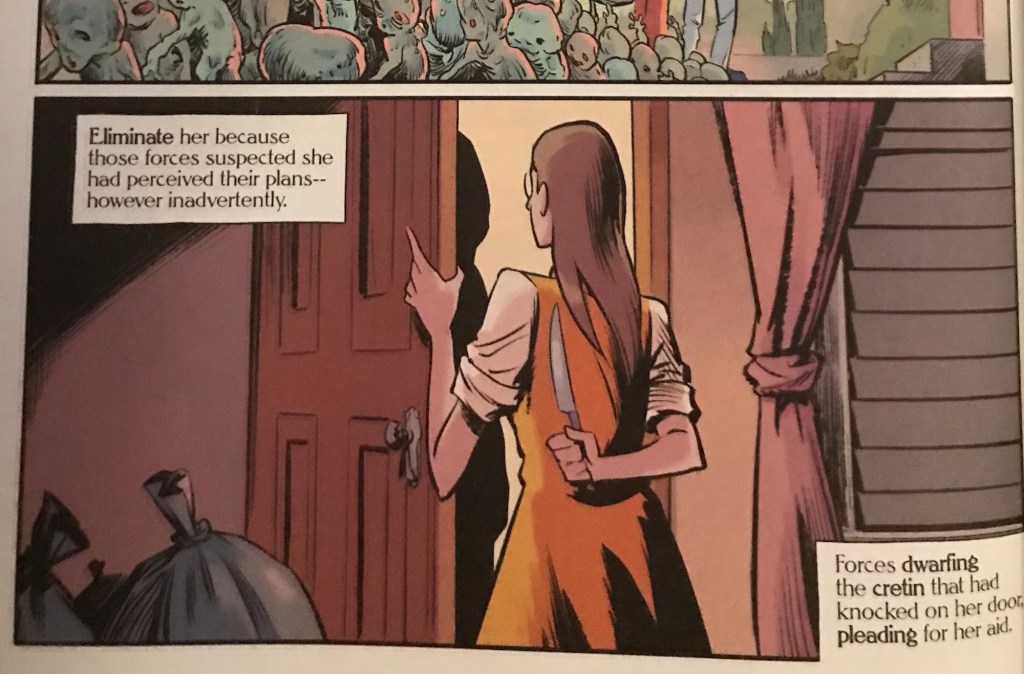

The overlooked nail that catches on the sweater is a recurring plot device in this story. Once Ruin makes it to the waking world, he looks for the only person he knows there: Jophiel, who hates him and immediately tries to drop him off on Heather’s doorstep.

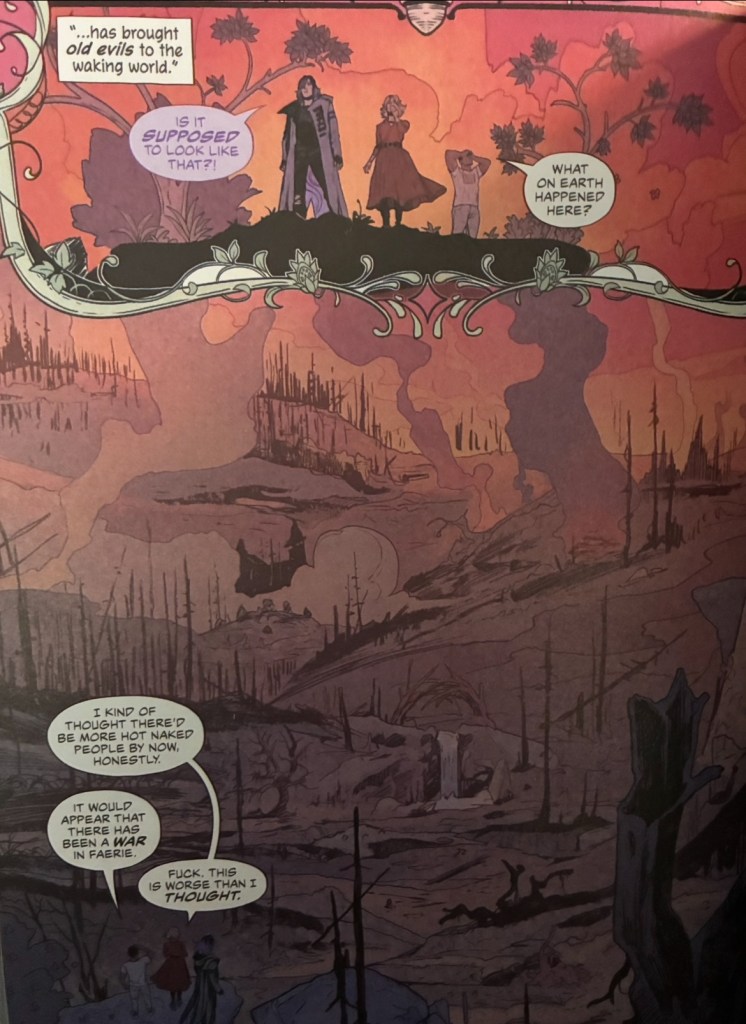

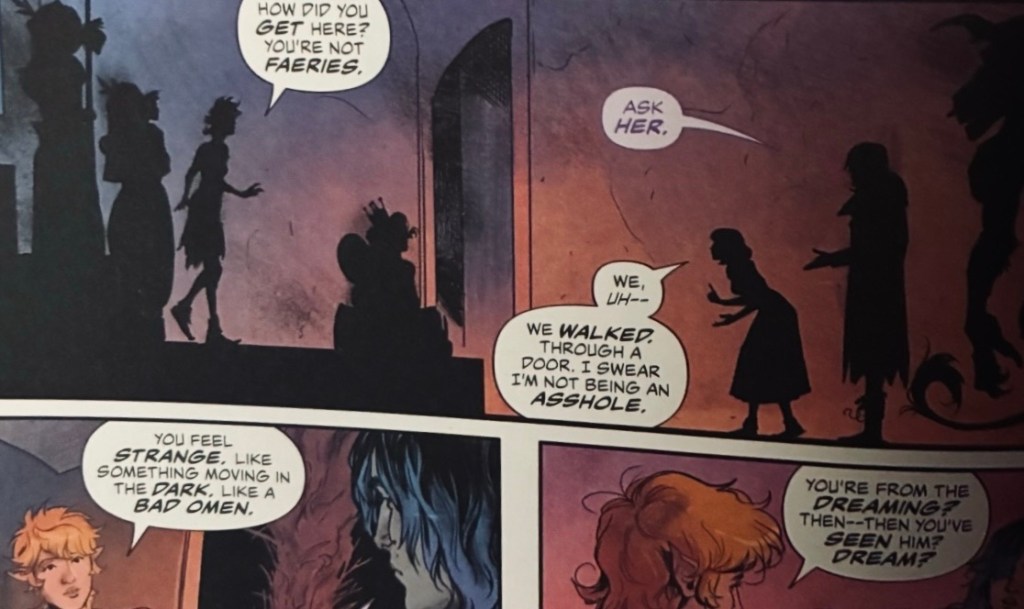

Heather hopes to rescue Lindy through an indirect, adjacent entrance to the Dreaming: Faerie. She combs through the ether for a being that’s closer to Faerie than they are and hooks Robin Goodfellow. Being rather less of a negotiator than Jophiel, the Puck swears vengeance for the temporary abduction. Heather, Ruin and Jophiel dodge his immediate wrath but he keeps his word anyway.

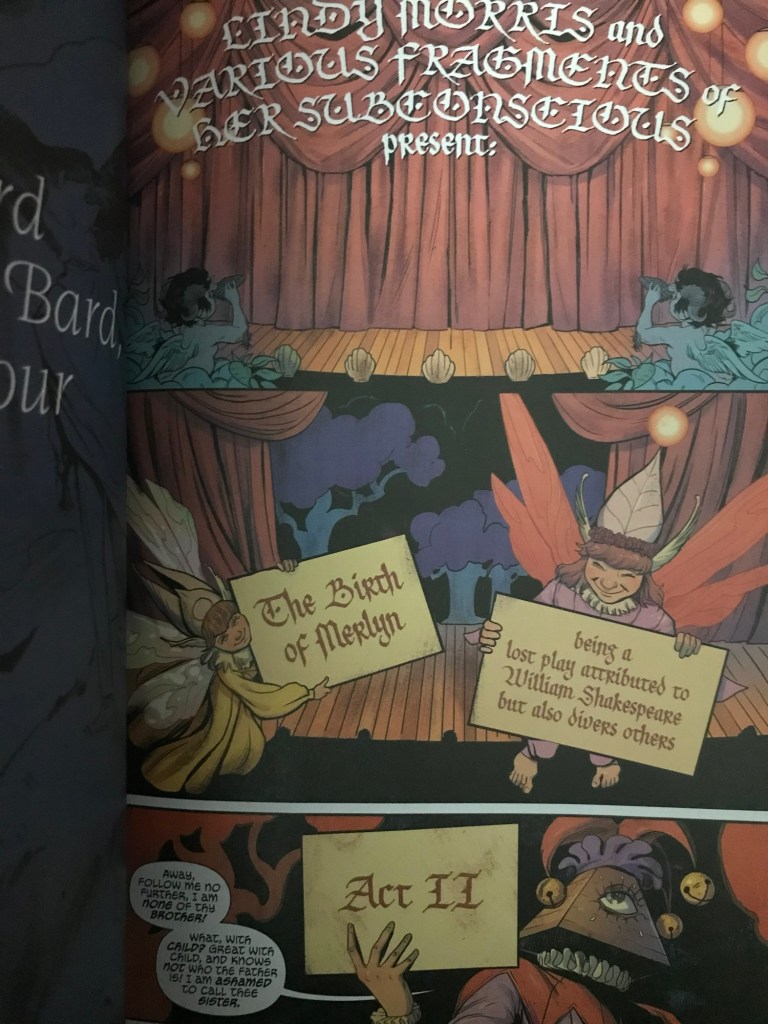

In the meantime, we are alternating with Lindy’s advantures in her dream construct. The Lindy arc succeeds as its own story but Sandman readers will wonder about the role of William Shakespeare. Especially since the SU Lucifer also riffed on the in-uinverse relevance of Shakespeare. It essentially depicts the in-universe events that shaped the idea that Dream imparted to Shakespeare, later to become The Tempest.

While we don’t get the kind of detailed flashbacks that SU Lucifer had, Shakespeare’s prior Sandman involvement comes through. Lindy becomes convinced that her dream will end if she solves an ongoing argument in her inescapable dream-house: she’s trapped with a bunch of different Shakespeares who are all convinced they’re the one that derived from the real, historical author. Details from the ‘Midsummer Night’s Dream’ vignette within Dream Country provide a random memory that one of the Shakespeares lets slip. This blurt gives Lindy an early, vital hint.

Like I said, it works fine as its own story. There is another possible association, though: Shakespeare is, potentially, the only one who spoke with Morpheus about the angst that drove him to suicide.

Daniel, the current incarnation of Dream, feels the stirrings of Morpheus-era memories.

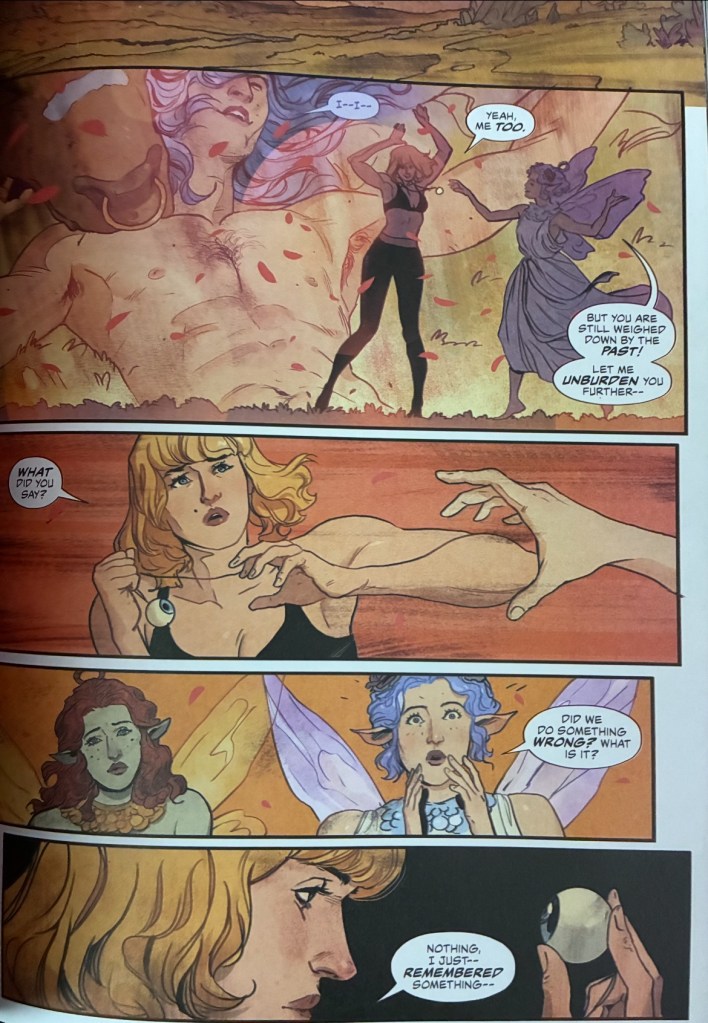

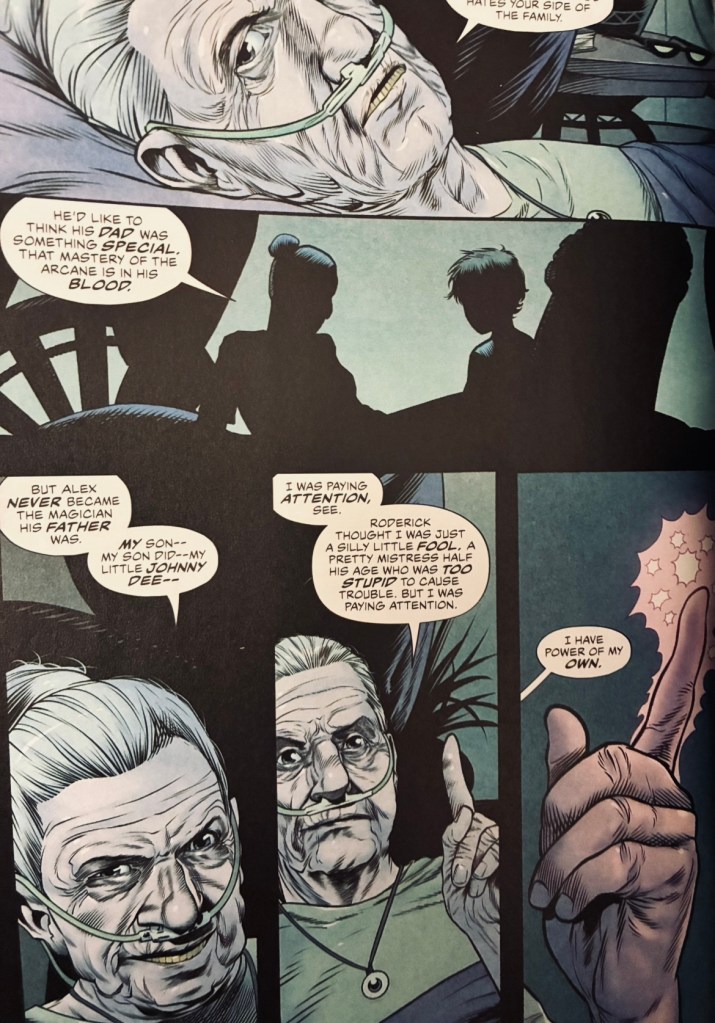

Speaking of those: Heather After is the granddaughter of Roderick Burgess- the guy who trapped Dream for eighty years during the early twentieth century. In fact- unless I’m missing something -it seriously looks like Heather is John Dee’s bio-daughter. Like, Doctor Destiny, from ‘Preludes & Nocturnes’; the Justice League villain who tried to claim Morpheus’s Ruby.

We aren’t given the exact details of her origin; save that she grew up in the lap of the Cripps family, whose magical heritage is at least as potent as the Burgesses, considering how a lawyered-up meeting goes between them during the reading of Ethel Cripps’ will.

On her deathbed, Ethel told Heather that she has no reason to be dependant on the Burgess family. Judging how Heather takes this information, I wonder about the kind of relationship the two of them had. Heather is a transwoman and it looks as if Ethel was the only one in the family who accepted her when she first came out. The chosen family dynamic is not spelled out in so many words but Heather’s reaction to Ethel’s death is telling. Ethel appears to have been the only adult that defaulted to her chosen name. She barefaces her way into the will reading, claiming to just want some of her grandmother’s personal effects to remember her by. Heather swipes a grimoire and casts a barrier spell behind her on the way out, leaving the Burgess and Cripps lawyers panicking and slinging spells at each other.

I did say she had a history of successfully managing risk.

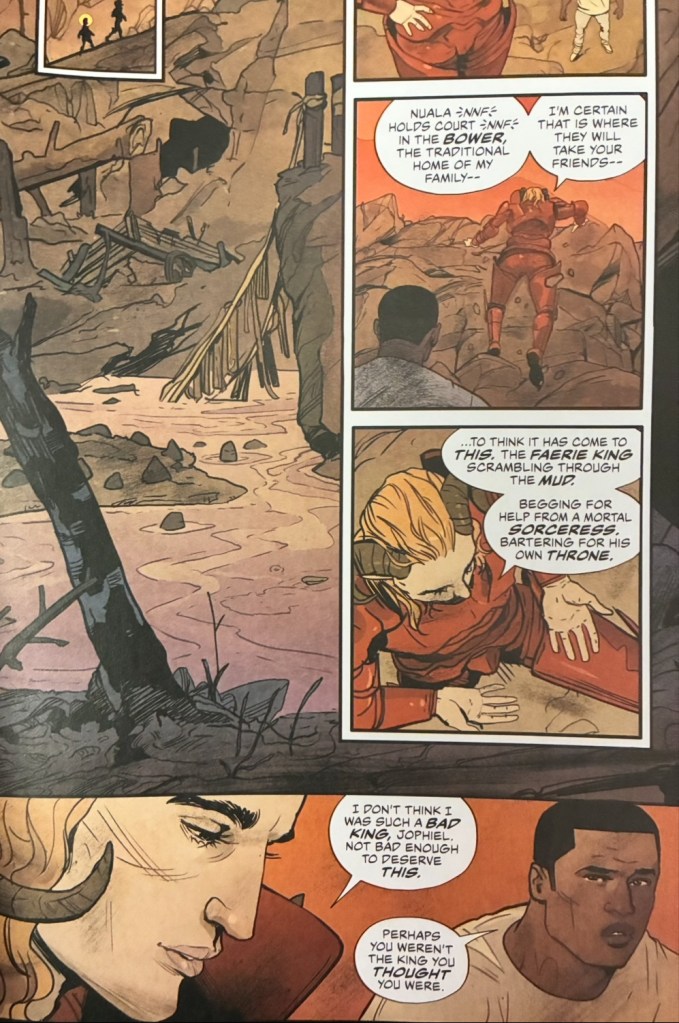

Coulda did better with the Puck, though. If you piss off one fairy then it pays to have either fairy allies or negotiation leverage with other fairies. She manages to persuade Auberon to help her out but only in exchange for a favor.

Nuala has deposed Auberon and Titania and they want their throne back. Auberon does, anyway. Titania would like it back but spends most of her time as one of Nuala’s cringing courtiers.

It’s tempting to wonder about the tension that was growing between Nuala and Titania during ‘The Kindly Ones’; buried romantic or sexual jealousy over Morpheus. The Netflix miniseries brought some of that closer to the surface but it was evident in the original comic as well.

I also couldn’t help wondering about Cluracan’s nemesis: the being he created by bumping into some raw creative energy in Dream’s castle. Off the top of my head, I think he eventually refers to himself as either the White Stag, the Wild Hunt or possibly both at different times. I wonder how relevant the second moniker is, since other beings use that name in the third SU Lucifer book. I’d be surprised if Cluracan’s nemesis was the same Wild Hunt that Lucifer crossed paths with. The Wild Hunt in SU Lucifer is an ancient and ineffible cohort, almost reminiscent of the Kindly Ones themselves…whereas Cluracan’s nemesis is relatively young. To say nothing of the possibility that the shape-shifter filled the void of the Hunted God, which Lucifer previously believed to be annihilated.

(I hear that the first run of The Dreaming snipped that loose end but I can’t help being attached to the theory that Cluracan’s nemesis somehow went on to become the Hunted God in SU Lucifer. In ‘The Wild Hunt’, Odin says that Lucifer’s doom was set in motion by one of the Endless)

Anyway, Cluracan’s shape-shifting nemesis gives Nuala almost as much shit as Titania does in ‘The Kindly Ones’. He appears in the shape of Cluracan to threaten Nuala and gloat over her during ‘The Wake’.

We do get Nuala’s version of things eventually but it’s rather short and not very specific. She makes no mention of any party external to herself, Auberon and Titania except the Unseelie. From the context offered here, the Unseelie were always present in Faerie but never rose to the level of visibility as the Seelie characters.

As for the ‘Waking Hours’ characters, everything that has happened so far either dates back to Heather accidentally summoning Jophiel or accidentally summoning Robin Goodfellow. I don’t recall any specific reason to think that Heather’s summoning of Jophiel played a part in Jophiel’s failure to guide Benedict but it feels plausible. In any event, Jophiel blames Ruin exclusively.

I mean, she seemed to accidentally summon Jophiel shortly before Ruin showed up? And Jophiel being who he is, I don’t think he’d be civil and friendly with Heather if he thought she had anything to do with it.

Even if that one is open and shut, though…none of the second half of ‘Waking Hours’ would have happened if Heather had not snagged Robin Goodfellow at the beginning.

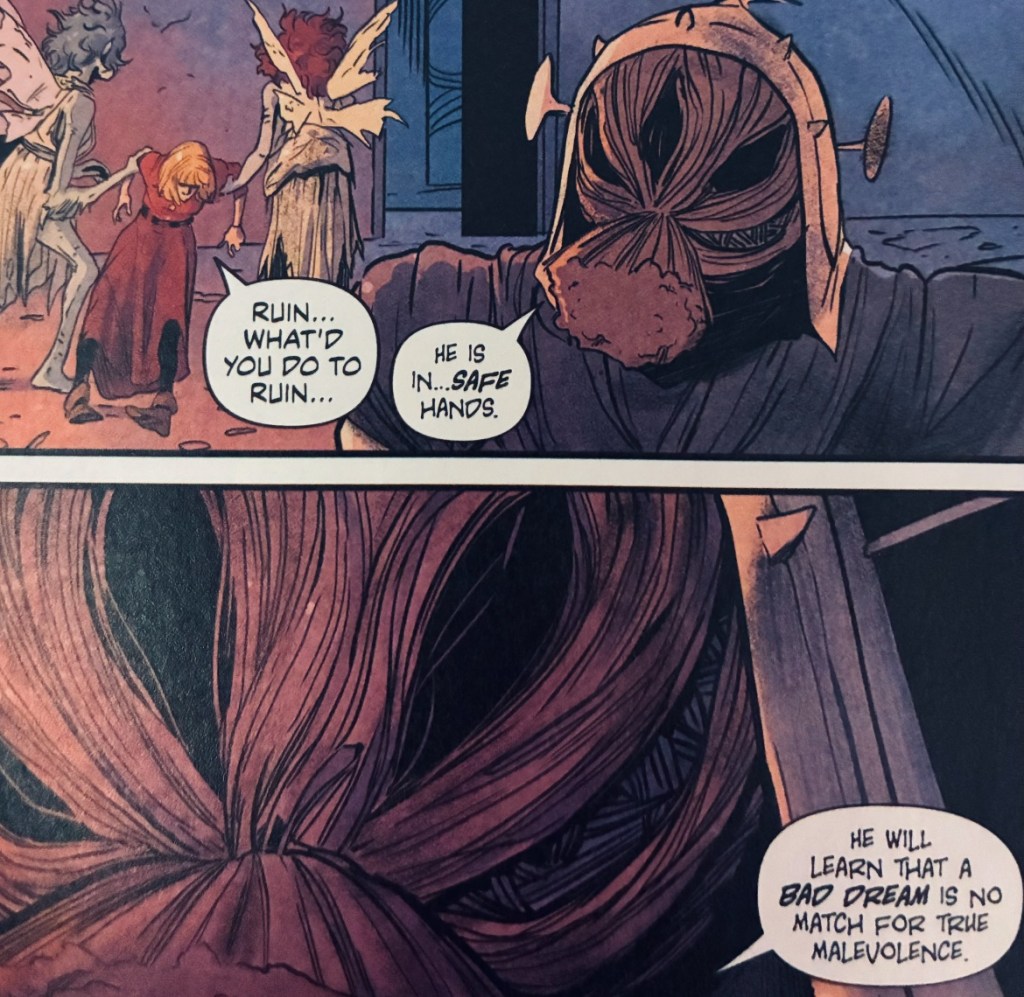

There is nothing to be immediately deduced from this just now…except for Dream’s belief that a nightmare (Ruin) wandering different planes “has brought old evils to the waking world.” When he examines the hospital room where the curse from Puck’s blade grew out of control, he says “(t)here is a coalescing in this place…the spiral of time doubling back upon itself…warning us that that which has happened before will happen again”.

We have also known, since the beginning of ‘Waking Hours’, that a descendant of Roderick Burgess is involved. Dream has only lately figured that out which he probably took for confirmation. Since Dream attributes all this to a nightmare outside of the Dreaming, his suspicions probably run closer to Jophiel’s.

It is also evident when Dream decides to take Ruin back to the Dreaming. He sees the localized effects of a localized cause. This part is also interesting because Dream shifts from distant observer to direct participant. His position- relative to the other characters -becomes antagonistic. Possible foreshadowing of later developments in Hellblazer and Nightmare Country (perhaps going as far back as House of Whispers)?

In all fairness…Dream’s role in the later Sandman Universe comics has been closer to strict neutrality rather than antagonism but- considering how ‘The Glass House’ ended -that shade of gray is going darker. His behavior in ‘Dead in America’ also stands out in contrast to Morpheus. Morpheus was a stickler for the rules and had zero compassion for those on the losing side of them…but he didn’t exactly relish flexing on his enemies like Daniel does.

I wonder if ‘Waking Hours’ was the early turning of this corner. I wouldn’t be surprised if the third volume of Nightmare Country sees Dream getting even more cozy on the dark side.