Final Fantasy XVI attempts something simple: a classic FF story- like one of the first five games -with cinematic realism.

With the creative direction Square Enix has been going in for the last few years, a turn-based game was never likely. FFXV and VIIR mainstreamed the action-RPG for Final Fantasy.

Meanwhile, in the gaming landscape in general, turn-based RPGs are thriving in niche communities. My favorite recent examples of this are the newer Persona games and a curveball from UbiSoft that I want to review here sooner or later called Child of Light.

Classic turn-based RPGs still have their place, but Square hasn’t relied on them in awhile.

We knew that FFXVI was going to be an action-RPG. Which is not the Final Fantasy a lot of us grew up with. Final Fantasy has always been a blend of gaming and storytelling, though. This is where it gets classic.

The centrality of the storytelling makes FFXVI feel like a hyper-cinematic game like Life Is Strange.

Not the same genre at all but the focus on story is equivalent. The hyper-realistic cut scenes and the limiting of the scope to immediate relevance and plausibility has a cinematic effect. I would recommend this game more to a fan of Life Is Strange or Heavy Rain, so long as they also like action-RPGs.

So if you’ve heard there’s a ton of cut scenes and it’s linear, you heard right. This involves something else that the fan base appears split on: the lack of a party. The player controls Clive directly for most of the game, which limits the audience perspective to one character.

Square Enix obviously wanted to embrace the button-mashing freedom of solitary melee. This was likely the influence of Devil May Cry developer Ryota Suzuki who worked on FFXVI. The closest basis for comparison, for me, would be the Salt games from Ska Studios and Vigil: The Longest Night.

Lots of freedom with one character and no player-identification with any other can make a narrative-focused game feel isolated. At the same time, the other characters appear more autonomous and therefore more real. The boundary between Clive’s agency and everyone else is firm, which builds immersion.

This is especially evident when a looming catastrophy hasn’t happened yet and appears preventable. The clash with Garuda felt very reminiscent of the Eikons at Phoenix Gate.

Both Benedikta and Ifrit creep into danger. When Ifrit brutally pulverized Phoenix, I kept wondering if I did something wrong to make that happen. Benedikta is both in and out of control. She is the head of Waloed espionage and is capable of far-sighted manipulation. At the same time, she is caught in a crossfire. Her duty to keep the second fire Dominant captive is the only reason things escalate at Caer Norvent. She has a duty; but after her first battle with Clive, he instinctively saps her dominance over Garuda. The agony of this loss is visceral. At that point I wondered ‘Was any of this ever necessary?’

Of course it was. Benedikta was operating under a clandestine plan between herself and Barnabas to unite the Eikons and their Dominants, by force if need be. She is duty-bound and she is uncomfortably aware of it.

Before her first clash with Clive, Benedikta attempts to recruit him. She makes the same offer to her old flame, Cid. The player has already seen her emotionally and sexually manipulate both Hugo Kupka and Barnabas Tharmr. We know she’s a puppet mistress. After her dominance over Garuda is stolen, though, these repeated offers have the same effect as Clive’s ultimatum.

Benedikta never would have handed over the second fire Dominant and Clive never would have joined Waloed. After she noticed the absence inside of her, I wished one of those things had happened anyway. Her repeated offers tell us that she was aware of her lack of autonomy in all of this. She cannot do otherwise; her only hope is that someone else can.

In an earlier post during my blind play-through, I mentioned the dissonance between Clive’s conviction that he must have killed Joshua, as the Dominant of Ifrit, and the circumstantial evidence indicating that it’s not that simple. This tension is exacerbated by Clive’s prior thirteen years as a warrior-slave. For thirteen years, he had nothing but brutality and grief. As Clive’s only connection to the past, his grief became all-important. Living for one thing, and one thing only, is precarious. The highest hope is that the one all-important thing never changes.

Clive’s realization that he’s the Dominant of Ifrit changes the one all-important thing.

Without his place in his world, the full weight of all that trauma and grief comes crashing down and Clive starts to wrestle with suicidal ideation. When this happens, Cid does his best to reason with him but that only goes so far. To Clive, Cid is a reliable and good man, but still a stranger. Clive only attempts to think logically once he is able to talk to Jill. When Clive and Jill return to Rosalia, the suicidal ideation sits uncomfortably beside his growing emotional awareness. I wondered if he was really going to walk into his own death just as he’s beginning to understand his feelings.

That sense of teetering risk was magnified by Clive’s exclusive connection to the player. On one hand, it can’t happen; that would be an awkwardly short game with an awkward ending. But Square has conducted bizarre experiments before. At the same time, Clive’s feelings weigh strongly in that direction and he has only lately, tentatively, begun to think of alternatives.

This tension, for me, was more interesting than the quest for revenge was. After we learn that Clive will not imminently commit suicide-by-monster/other-Dominant/Echo, his commitment to the Hideaway is a breath of fresh air.

Maybe this is nothing more than my interpretation. What makes me think it might not be (or, at least, not just my interpretation) is that it sets important reference points for some of the most powerful scenes afterward.

The storytelling is absolutely central to this game. It’s not an even split that relies on visual and circumstantial storytelling, like Metroid or Bloodborne. Like I said, think Life Is Strange. Or, better yet, Vampyr with more action-RPG emphasis. The division with Final Fantasy XVI is closer to sixty-percent story and forty-percent game. That’s something that will either make or break it for a lot of people.

Plot isn’t everything but- if you want a story that carries its own weight -then plot has work to do. Like other Final Fantasy games, there are plot points that depend on the player’s inferences. The more important the plot point, the more important it is to express it. If an important plot point is communicated by implication, then the circumstances that imply it must succeed.

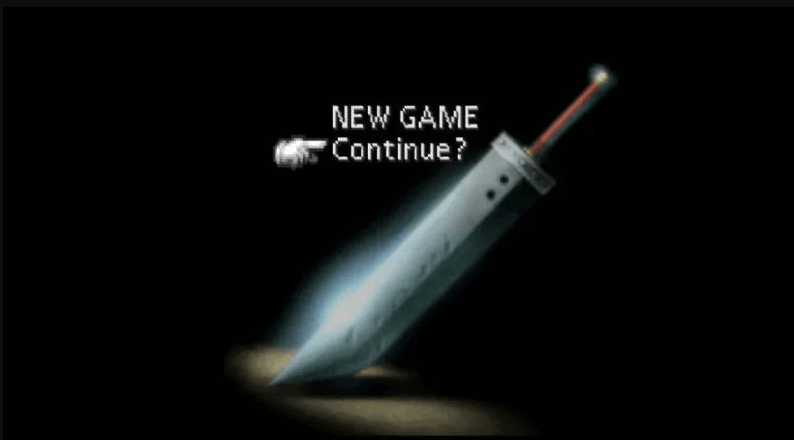

There are genre conventions that address this. A well-written detective story depends on the reader observing things while they happen and connecting dots before the mystery is solved. A number of Final Fantasy games have attempted this. Their biggest success was with the original FFVII. There are certain details in XVI, though, that are built up by understatement that can be easily missed. Many of them set up the story’s final act.

And the storytelling, like I said a million years ago, is where we find the deconstruction of classic Final Fantasy.

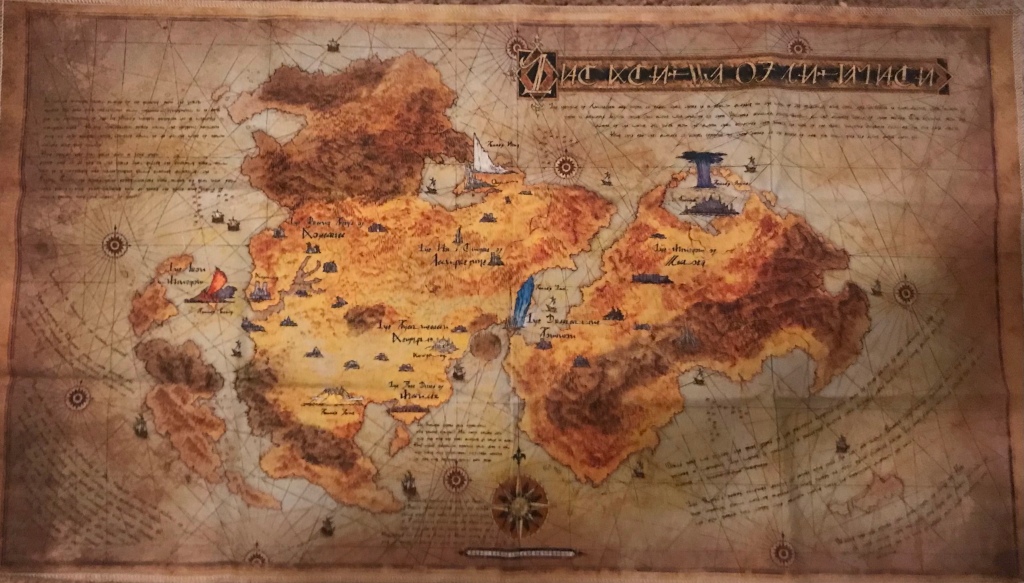

As far as I can tell, most of the lore precedents for XVI were established before VII. We got crystals, summon monsters, ancient founder civilizations, elemental magic, corrupt institutions and moral reversals. All of which were Final Fantasy touchstones before the jump to 3D. This short list of old standards are the main ingredients.

In the west, many gamers associate games with alternating mechanics with JRPGs. Many westerners likely encountered combat screens and birds-eye exploration screens for the first time with JRPGs.

Like I said at some length in an FFVII post, these divisions had a basic appeal to the imagination back then. The combat screen is not a literal depiction of a battle. Things like active time bars and experience points don’t have any diagetic existence within the fictional worlds. When I first got hooked by VII, I used to wonder if the Dorky Faces and Hellhouses are literally real or are representations for things like hauntings. At that point, we also know that summoning Bahamut in VII doesn’t literally lift the ground beneath your foes and vaporize the floating island in midair. Summoning Ifrit in X won’t leave regular craters in the ground behind you.

As the most cinematic Final Fantasy, XVI does not have this separation between representation and reality. Shifts in proportion are implimented as cinematic themes.

One of the most memorable cut-away cinematics focuses on the ongoing war between Sanbreque and Waloed and their respective Eikons: Bahamut and Odin. Sanbreque has just lost ground in a border war and Waloed is marching inward. Odin steps in and is met by Bahamut in a battle that probably would have been depicted a million different ways in older FF games, especially from the player’s perspective. With as much abandon as summoning Knights of The Round in VII or Ark in IX for sheer amusement. There were comparable moments like Phoenix Gate and Caer Norvent but our first look at Bahamut and Odin goes further. That was the first time I felt like I was watching a cinematic version of what battles between summon monsters would look like from an earlier game.

Other details of the event draw your attention to other differences of scale. These two Eikons are the totems of nations, with armies behind them. The entrance of a single Eikon into a military battle is a stretegic decision. As we saw earlier with Shiva and Titan, two Eikons is a gamble for both sides. After winning the strait of Aurtha, it was worth it for Odin to press the advantage on behalf of Waloed. Sanbreque can continue to fight with an army and get wiped out by the giant flying kaiju on a giant flying horse…or they could try to hold their ground the only way they can: with their own Eikon. So Bahamut manages to keep Odin at bay and shortly afterward receives word of civil unrest at home. Prince Dion won’t leave the field because- once he does -Barnabas can turn into Odin and destroy the Sanbrequoi army. Barnabas would never leave the field for the same reason. Meanwhile, riots at home have struck close to the Sanbrequoi capital.

Sir Terrence adds, with worry, that they will not be receiving any previously-requested reinforcements. Those forces are needed at home. Meanwhile, Sanbreque is playing defense with a dwindling army and an Eikon.

The haplessness of Prince Dion adds to the dramatic scale. So does the worldbuilding forces at work in this scene. Clive’s own battles reach greater proportions later with Titan and Bahamut. But the confrontation between Clive and Barnabas in Waloed is different. It made me feel that, for the first time in the story, Clive was approaching the level of Eikon mastery that Dion needed to hold his own against Odin. This is built up by a moment of dialogue that implies that there has never been a question of royal succession in Waloed: Barnabas is corporeally ageless and has ruled his country for eons. When Barnabas and his mother first landed on Waloed’s shores, there were cities and territory to conquer, so I hesitate to say that Waloed has only had one king…but it definitely looks like it.

In any case, Clive only rises to the level of a divine combatant once he is pitted against an ageless human who has lived with his Eikon for mutliple human lifetimes.

If it makes sense to talk about a Dominant, with an Eikon, literally becoming a god of their nation, then Barnabas has done it. In a ‘might is right’ paradigm, Barnabas is the most ‘right’ and epitomizes what Clive and Cid’s Hideaway are fighting against.

If the narrative use of graphics and proportion is a strange thing to dwell on, consider how rare it actually is in Final Fantasy. Even XV couldn’t have every explosive spell or Astral summon leave a permanent mark on the continuous map. Which is not a problem: it’s rational game design. We don’t need to see a literal, in-world consequence of every mechanic because we understand we’re playing a video game. All of which is why XVI is so different for not allowing the player to do anything that’s not directly explicable in-world. When exceptions materialize, they have exceptional consequences, such as Clive being the only Dominant to control more than one element.

In my own writing, I try to remain aware of something I think of as plot economy. Everything a storyteller introduces is something that an audience will notice. Every innovation has consequences that can either help or hinder the body of work. The uniqueness of Clive is a good example of this. The crux of its economic value is introduced almost immediately. Just before Lord Murdoch is killed by Ifrit, he says that there is only one Eikon for each element. Cid confirms this. Another Dominant, Benedikta, can create lesser emanations of her Eikon Garuda. The Eikons Shiva and Odin both are accompanied by semi-divine companions: Torgal and Sleipnir. Conversely, Ifrit and Phoenix can combine into a single Eikon.

The doubling, splitting and combining is introduced by Clive and it’s never far from him. This is introduced beside the pivotal use of visual storytelling: the uniting of the Eikons.

As the absence of open world exploration accommodates a set narrative, it’s worth talking about the gameplay that is present. This is, obviously, the most combat-oriented Final Fantasy ever made.

Other than the Dissidia games, of course. Among Square Enix RPGs, though, XVI is the most combat-oriented. Yet not without precedent: both Crisis Core and Type-o were heavily combat-focused with limited narrative freedom. What distinguishes XVI is the possibility for new combat builds with each Eikon absorbed by Clive.

Things hit a sweet spot once every Eikon is unlocked. Eventually, you can even ‘master’ the circle button moves which leaves the range of move-sets pretty wide open. My usual is a fast/aerial combat set based on Garuda with preference given to airborne Eikon abilities in the other two builds (up to three can be socketed). I made a range-fighting build using Ramuh and Bahamut abilities. I nicknamed it the Mega Man build but the combat is still more action-RPG than run-&-gun. Ramuh’s circle ability, Blind Justice, is a good slow-burn strategy against foes with high defense.

Blind Justice consists of launching electric projectiles that cling to the target and explode the next time you use an R2 Eikon ability with square or triangle. This delay means that you have a chance to launch as many as your patience will allow for maximum impact. This also brings the skill requirements back to my usual speed/rogue preference.

Shiva’s Cold Snap ability with its temporary paralysis might feel like a good fit but don’t do it. The amount of time needed to launch a few Blind Justices is better served by enemy cool down time and distance. And Cold Snap requires melee distance.

Cold Snap is a better neighbor for melee abilities that need a hot minute to charge. It’s a dash/leap variant that allows you to pass through enemies while briefly freezing them, which works great in conjunction with a “rogue”-styled move set. With Cold Snap mapped to the circle button, my two favorites for the square and triangle slots are Rook’s Gambit and Upheaval.

The best of the mixing and matching only opens up late in the main scenario, though, with most of the experimentation happening in ‘Final Fantasy mode’. Combat is the central game play mechanic and the tougher post-game battles with late-game enemies showing up earlier give the biggest incentive for experimentation. That being said…the trial and error experiments don’t usually take long to wrinkle out in the first half, before Clive takes over the Hideaway.

While combat may be the central mechanic, it’s not the only one. Even if a game play-centered review might not consider the cinematic cut scenes, story beats or lore text…it should be obvious that just as much effort was spent on these details as the game play. Even if not directly relevant to game play, those details were clearly intended as an equally significant part of the overall experience.

Case and point: side quests. Many of which are pretty common tropes in RPGs. In FFXVI, the game play in side quests will consist of interacting with NPCs, fetching, fighting and light exploration. A roster of bounties for boss-tier monsters ocassionally intersect with some of these jobs. With these familiar side quests, everything else has to do more work, such as gameplay, graphics and the exceptions to the rule.

The plot gets in on the action: after the death of Cidolphus at Drake’s Head, Clive becomes the leader of the Hideaway and the current bearer of the Cid moniker. He is at the heart of the community’s leadership, which makes him responsible for the people who depend on the Hideaway for protection. This gives the side quests something that they should have more often in other games: a point. It makes sense for him to be intervening in the matters of others and it makes sense for the people of the Hideaway to expect this.

There are also chapters of the mainline story that resemble side quest-like activity, such as travelling the world map and looking after material needs and political relationships of the Hideaway. These demands of infrastructure and problem-solving restore part of Clive’s birthright. He may not have the title but he definitely lives the life of a Duke with subjects.

There are side quests that flesh out the world of Valisthea. Most frequently: the lives of Bearers under the increasingly brutal crack downs. At the same time…there are far more random fetch quests, running stuff back and forth and hunting monsters. Many side quests just aren’t very rewarding, in terms of gameplay or worldbuilding. This seems like the kind of problem that could have been easily solved if Square Enix just spent a little more time developing Final Fantasy XVI. Many gamers complain about Square’s long development cycles but this is one instance where they should have taken longer.

This is the problem with XVI’s side quests: Clive, once he inherits the name Cid and assumes leadership of the Hideaway, has more of a reason to do “side quest stuff” than most RPG protagonists. Clive has an authortitative title and it comes with the messier responsibilities of leadership. In this way, the “side quest stuff” has direct relevance and it makes sense for Clive to address them whenever he can…and whenever you can is how side quests work. But the side quests needed more actual game design, which lets down the perfectly good ficitonal set-up.

Another concept that depends on the harmony of graphics, writing and gameplay is the dungeon experience. You’ll be moving the story a lot just from walking around between different regions. There are also smaller, more limited infiltration gigs that involve destoring the Mothercrystal in this or that country or rescue missions. The only time I really felt like I was entering a “dungeon” in a typical RPG sense was when the Ash continent and its ruling country of Waloed were finally unlocked.

Two continents with one being mostly dead reminded me of Final Fanasy XV. As the “open world” FF, XV missed an opportunity by putting Niflheim on rails. XVI is far more linear but it’s desolate “final dungeon” actually felt liberating. In XV, Noctis is connected to a wider world of context (at least as a young adult, before the flash-forward). When Noctis and his retinue show up in Niflheim, they have context from reliable, institutional sources. When they see how suspiciously empty Niflheim is, there are a few reasons the player could imagine based on the geopolitics experienced by the main characters.

In XVI, Clive embodies something of an institution himself: he leads the Hideaway. XVI is also set in a world without the (twentieth century) media infrastructure of XV. Waloed is also more comfortable with naked aggression than Niflheim. Niflheim, of course, had a long history of warring with Lucis. But in the continuity of XV, Niflheim is at a crossroads. There is a militaristic ploy hidden in their final act of diplomacy which sits uncomfortably beside knowledge that Niflheim is gambling with it’s very last diplomatic opportunity.

Waloed waved bye bye to all that a long time ago and are secure in the knowledge that they are no one’s friend. Monarchies in Valisthea are typically held by the bloodlines of the Dominants. Many Dominant-monarchs hesitate to take to the field of battle because, on one hand, the ability to transform into the giant, kaiju-like Eikons is a major military assett. On the other, the Dominants are hereditary rulers and it’s not easy to bet your monarch. The Dominant bloodlines and their control over the Eikons appears to serve a function similar to nukes in our world: a deterrent rather than a serious option. Barnabas Tharmr, the King of Waloed, regularly fights alongside his army as Odin. Dion, the prince of Sanbreque, is seen as uniquely brave for transforming into Bahamut and meeting Odin on his own terms every time. Waloed is clearly willing to cross lines of traditional conduct that other Valisthean nations are not.

Waloed openly buys up resources in other countries after exhausting their own and their espionage apparatus is relentless. In the present of the story, any connections Waloed has to other nations are secret, such as the collaborations with Dhalmekia and the Crystalline Orthodox. In polite society, Waloed is a pariah state. Benedikta, Cidolphus, Sleipnir and Barnabas gather a lot of intrigue simply by being from Waloed as well as the fact that none of them say anything about it. Benedikta or Barnabas wouldn’t talk because one’s a spy and the other is the head of state. Sleipnir is a supernatural being; a kind of familiar for the Dominant of Odin (Barnabas). Cidolphus is a defector, though, and presumably has no love for the homeland that made his life and his duty impossible. The only reason Cidolphus would keep quiet would be personal plans of his own and/or a visceral avoidance of the memories. Waloed therefore has more of a mystery to explore than Niflheim.

It may not have been the total exploration feast I wanted it to be but the Waloed segment also had the most satisfyingly complete ‘party formation.’ I know I know: that’s not what this game does. If it did, though, the most complete party would be when Clive, Joshua, Jill and Torgal all go together as a party toward the enemy’s home turf. This is also, like I said, when Clive’s mastery over all the Eikons is at its most satisfying during the vanilla play-through.

However familiar we become to Clive’s unique powers, though…it remains a mystery in the world he lives in. A mystery with consequences for the other more familiar worldbuilding details.

Like ancient technology and their metaphysics. Mothercrystals (at least some of them) are close to porous dimensional veils. Clive has a handy dandy game mechanic enabling fast-travel through the obelisks which, in-world, would have to be teleportation using old technology. The shortest distance between two points stops being a straight line with space-time warping.

This makes more sense when we see Dominants lose control near the Mothercrystals. It is also common for Dominants to lose control when the astral presence of Ultima is nearby. This happens with Clive, at sixteen years old, during the asualt on Phoenix Gate. His deranged rampage as Ifrit happens immediately after glimpsing Ultima. The astral presence of Ultima also appeared to be a factor during the Sanbrequoi frenzies of both Ifrit and Garuda. Ultima was physically present when Dion rampaged. There are none of the typical signs of Ultima when Hugo snaps but Hugo’s progressive madness is triggered by Clive and his growing power in the world. When Hugo truly loses it, he physically devours the Dhalmekian Mothercrystal to absorb its power and defeat Clive. Cid, the Dominant of Ramuh, dies when he attempts to shatter the Drake’s Head Mothercrystal while channeling his Eikon. Afterward, we get our first glimpse of Ultima’s true shape, like a sacrifice was offered to open a gateway.

The autonomy of NPCs become more believable when they are made to act before thinking. Slowly but surely, we learn that the madness of the Dominants is the sanity of Ultima: our antagonist. I hesititate to say ‘villain’ since that word is usually thought of as a more human force motivated by human reasons. Maybe that’s nothing more than an antagonist with a personality. Ultima, though, is closer to the monster in a monster movie.

Square Enix has done both kinds of antagonist before. Villains like Kefka and Sephiroth are some of the most beloved Final Fantasy characters. On the other end of the spectrum, there is Orphan and Barthandelus in XIII, who are non-human puppet masters. Ultima may be closer to Orphan than Kefka but he still has a few character beats.

Near the end, Ultima delivers a lot of explication about things that only he was around to see firsthand. Lots of things, such as the insanity of the Dominants around either Ultima or Clive, are explained in his words. Because there are so few other sources that contradict him, we are tempted to take Ultima’s words as authoritative.

Fair warning: the following includes my personal inferences and interpretations.

The meaning of Ultima’s words is so important to the plot that it can overshadow more subtle, adjacent details. Por exemplo- he only tells his side of it. He mentions events where he acted unilaterally but makes no comment on whether or not he was alone. And we’ve seen the Fallen ruins so many times throughout Valisthea that they might fade into the background. He says he was once part of a non-human, non-corporeal society that only found itself in Valisthea after the fall of their homeworld. He also says that the (apparently few) other immigrants he arrived with became the Mothercrystals, offering their magical bounty to the world of Valisthea to shape it into the place that will produce a being called Mythos. Known to us as Clive Rosfield.

Ultima sees Clive as his eventual physical vessel. Clive, meanwhile, destroys the Mothercrystals and absorbs the powers of the Dominant bloodlines. In the end, this is confirmed as a means of “releasing” Ultima’s peers. Only into one body, though, to be subsumed by one personality.

Either Ultima betrayed his own people…or his people were always a colony organism to begin with. What clarified this, for me, was the revelation that Ultima crafted the Eikons based on a common model: Ifrit. There were, apparently, eight original Ifrits which were chanelled, through the Mothercrystals, into the eight Eikons. This makes for a total of sixteen (ta-da!) different Ifrits.

If there’s something from Clive’s childhood that he never forgot, it was his mother’s rejection. Why did she reject him? Because he wasn’t the Dominant of Phoenix and his mother Anabella comes from a bloodline known to be able to create Dominants. Clive was her first child with the Rosalian Duke but, without the Eikon Phoenix, Clive could not inherit the throne. Joshua, instead, became the Dominant of Phoenix. Before the disaster at Phoenix Gate, no one had heard of Ifrit. Just like, in the normal course of things, no one ever sees a prototype. Humans might start out as fetuses but no one you know is a fetus.

The Ifrit mold, it seems, is derived from what Ultima originally was before the “fall” to Valisthea.

I’m tempted to stop here and just do a mythic dive into that but instead I’ll just remind you of a few things: Barnabas believes all human effort is doomed to failure and only through the grace of a higher power do we have any hope. Hugo Kupka is a manic alpha male who constantly bristles but won’t change his behavior to nurture the loneliness that makes him worship the ground Benedikta walks on. As far as Hugo is concerned, no one loved him but Benedikta and once she’s gone there is no one else. Benedikta herself is trapped between knowledge that her future depends on authorities that will never change and she believes that if she could just say the right thing at the right time someone might see reason. Cidolphus helped build a monster, lived to regret it and dedicated himself to a life of good works in a desperate attempt to make amends. Dion is trapped between holding the Sanqrequoi frontier against Barnabas and a father that could undermine his life’s work with bad judgment. Clive barely survives thirteen years of trauma.

The only Dominant that is absolutely, rigidly sane, almost every time we see her, is Jill, the channeller of Shiva. And Jill spent just as much time off camera as Clive did, during the thirteen year flash-forward at the beginning, doing much of the same thing. Clive knows this and even prolongs the raid on the Crystalline Orthodox’s Mothercrystal for Jill to reap her revenge against her former slavers. Clive’s self-image went through several black and white shifts before Jill’s empathy helped him even out. Clive knows this and is dedicated to supporting Jill better than he was supported.

If cracks in your worldview and self-image are how Ultima “wakes up” in the mind of a conflicted Dominant…Clive is committed to not letting that happen to Jill. Unfortunately this also gets into one of the few moments in the story when I truly did feel like calling bullshit: leaving Jill out of the final battle.

The more I think about it the more I think there are in-world occassions for this. Providence, the “space ship” that Ultima is bound to, is suspended in the air. A winged Eikon of some kind, like Phoenix, is necessary. Dion, capable of channeling the dragon Bahamut, also tags along. If Clive can ride on one of their backs, so could Jill. But it’s posible that no one survived the final battle.

Personally, I hope that the attack on Providence wasn’t necessarily a suicide run. Joshua and Dion appear to die while Clive clearly dies. You know what? This is the second part where I call bullshit.

The ambiguity of the ending made me cling to other possible interpretations (ending spoilers incoming). We spent a whole game getting to know someone who is learning to make peace with being alive. But he dies anyway. Clive’s whole arc is about the discovery that the world isn’t just a giant cesspool of evil after all and that it’s worth it to keep going. Ending the story with a noble self-sacrifice feels dead wrong.

The lore precedents are not kind about this, though. If Ultima and his people were a psychic colony organism then they were, in a way, one being. It’s why Ultima planned for Clive to destroy the Mothercrystals and absorb the Eikons. This implies that, in order for Ultima himself to die, any body that could channel him must die to (kinda like Jenova in VII).

This interpretation at least leaves room for a more mysterious fate for Jill. She consensually allowed Clive to sap her Dominance over Shiva because it was the only clear way to avoid the destructive fate of a Dominant. Is Jill a loose end for Ultima to reappear through or did Clive close that door when he absorbed Shiva?

Either way I don’t like it. Maybe lore consistency requires Clive’s death but it felt backwards to the overall thrust of the story.

There is some genuine ambiguity here, though. Before the ending, certain characters express the fear that Valisthea may be doomed no matter what. If the Mothercrystals were introduced by the ‘Ultima race’ specifically to cultivate Valisthea…then it’s possible that the Mothercrystals have become existentially necessary. A few characters even speculate whether or not killing Ultima alone would destroy the world.

Post-credits, we get our biggest flash-forward yet. A household of children are enamored with a book called Final Fantasy by someone named Joshua Rosfield.

Joshua’s death in the final battle appears certain. If Joshua survived it could not have been because of anything on-camera. Yet he was somehow able to write the story of his adventures. If the world ends and people you know are still doing things anyway then maybe the new world succeeded the old. If Joshua reincarnated, other characters may have as well.

Dion falling in the final battle is also repugnant. LGBT characters are sacrificed for cheap pathos way too often. Like Clive, the lore appears to put Dion on the losing side of this equation. Out of all the Dominants to break down upon contact with Ultima, Dion’s encounter is the worst: he lives to see the consequences of his rampage. His aspiration toward redemption compells him to join Clive and Joshua. Dion wants forgiveness but he also understands that turning into a dragon and going on a killing spree in the middle of your own kingdom is not easily forgiven. The prospect isn’t good. After we’ve seen Clive turn away from suicide-by-duty, it stings to see it happen again so late in the story.

Every other Dominant driven mad by Ultima dies because they think they’re hopeless and then make themselves hopeless after a massacre. Dion stops just short of that. He experiences something none of the victims of Ultima do other than Clive: the struggle to go on, afterward. Dion may not expect much for himself but he does believe in the struggle. He sends his lover and his most trusted knight, Sir Terrence, to look after a mysterious child that nursed him back to health after his deadly rampage. From that moment afterward, he considers nothing but reparation and redemption.

Dion’s post-rampage arc is built by moments like his meeting with the “medicine girl” and his last meeting with Terrence. The hard truth and the duty it leaves him with are established. We know the depth of what Dion is experiencing because we’ve seen Clive go through it.

It’s not as reprehensible as the double-standard of Cecil and Golbez in IV. Cecil had a long and miserable journey toward expiation and all Golbez had to do was admit he was possessed. Maybe Cecil’s journey is supposed to soften us to Golbez but if so that needed to be better established. But the double-standard between Clive and Dion is still pretty bad. Obviously, the “succeeding world” interpreation with different incarnations for the same inhabitants is more attractive, if only because Joshua and (conceivably) Dion and Clive might still make it.

If the successive world is a world without Ultima, in which the whole epic is known only as a fictional novel, then it makes sense that Joshua (and whoever else) would be ordinary people. When the book and its author are revealed, it evokes the very beginning of the game with it’s mysterious narrator. My intuition tells me that narration was reading from the book and the voice was Joshua’s. The opening narration refers to in-world sources like Mors the Chronicler. To the people reading Final Fantasy by Joshua Rosfield, are these references just world-building or are they historical sources? It isn’t clear.

The problem with the succssive world theory is how to deal with the characters who do survive. If the post-credit scene takes place in another world then it follows that everyone in Valisthea died after the final battle and everyone reincarnated in the next world. Which would wash everyone’s hands anyway.

This successive world could furnish a lot of DLC possibilities, since Square Enix is considering DLC for XVI at this point. My preference for DLC would be something centered on Dion in which he gets his happy ending with Terrence. A story in the successive world about Clive would also be a good idea, if only to complete his “don’t kill yourself” arc.

XVI’s developers have also said that Clive and Dion were designed as thematic and aesthetic opposites. Dion spends much of the game keeping Waloed and Barnabas at bay. If Clive is Dion’s opposite equal and Barnabas is Dion’s enemy, it could be fun to imagine alternative timelines where the three serve different roles. Maybe in one of them Dion is Mythos, Rosaria is the seat of Ultima and Barnabas is the tragic Dominant living under an oppressive pall of remorse.

If the DLC is going to be a character-centered piece, like the first season of DLC for XV, I want that character to be Dion. If that one standard is met, I’ll probably be pretty happy with it. Beyond that…the fandom has ben uanimous on their desire to hear more about a mysterious Eikon called Leviathan the Lost. If they address that mystery from the ancient lore of Valisthea, it may be convenient to include other historical events…such as what exactly happened with Waloed to get it where it is.