This is a straight-laced, faithful adaptation. Which does not guarantee success. Worst case scenario (with comics, anyway) is a kind of paraphrasing or summary that is accompanied by pictures rather than taking place within them.

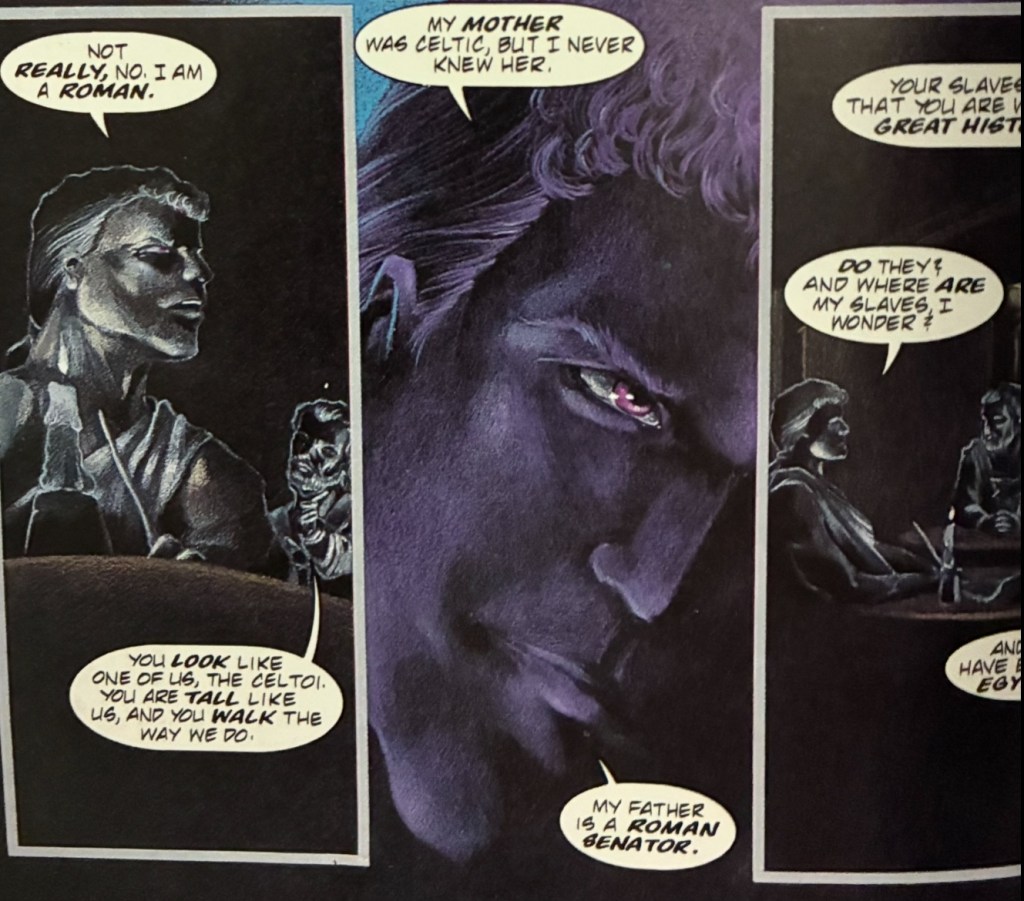

This comic prioritizes the novel’s first person narration and therefore takes heavily from the actual text of the book. To their credit, it looks like Perozich and Gross only wanted to draw the book. Allowances for context between mediums were made but, whenever possible, the text will consist mostly of Anne Rice herself, as Lestat’s internal voice or the various characters.

At the same time, it is not a complete reprint of the book. The first person narration is therefore scaled back whenever the immersion is served better by a purely visual sequence. This is a small thing but it’s a good sign. It says that Perozich and Gross don’t feel like the comic medium is an awkward obstacle that they have to work around rather than with. As good as it is here, though, it wasn’t the visual pacing that won me over.

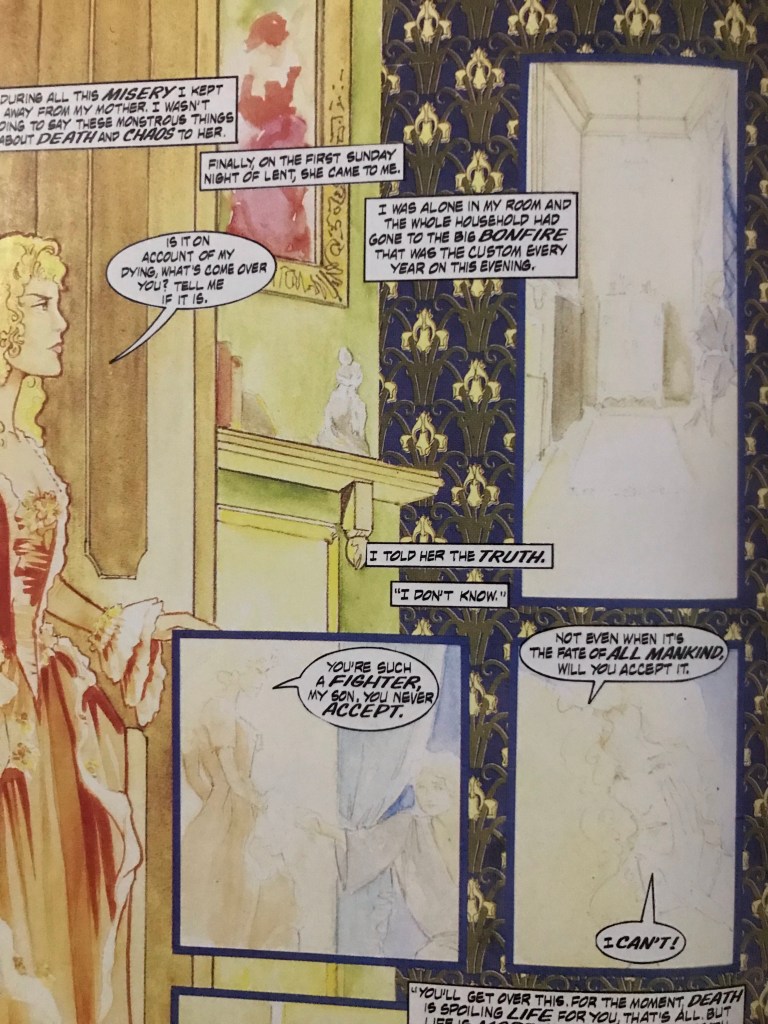

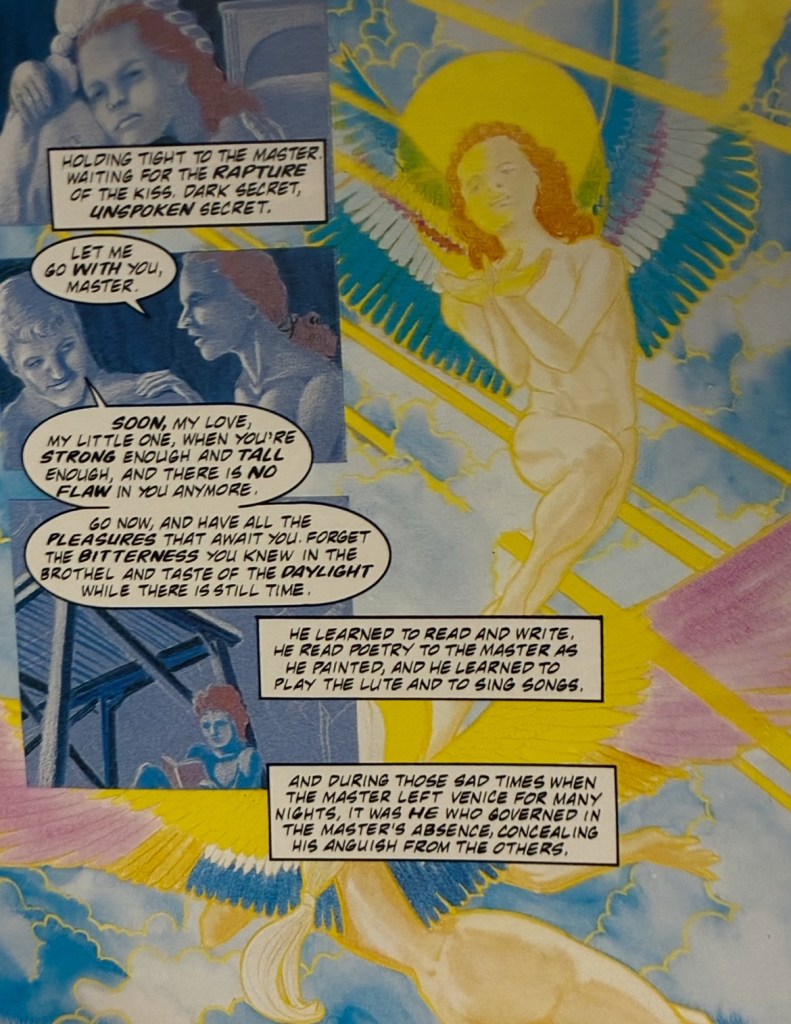

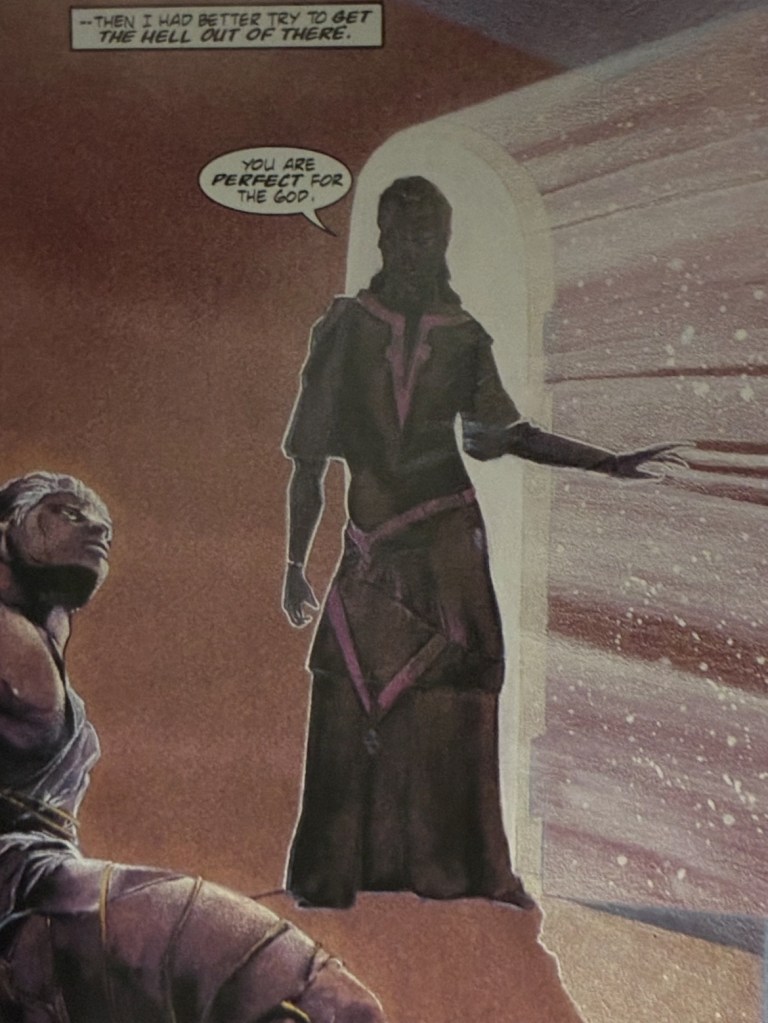

This is one of the pages that convinced me that Faye Perozich and Daerick Gross were capable of adapting Anne Rice. Or, at least, of conveying one of her vital nuances.

Spoilers ahead, fyi.

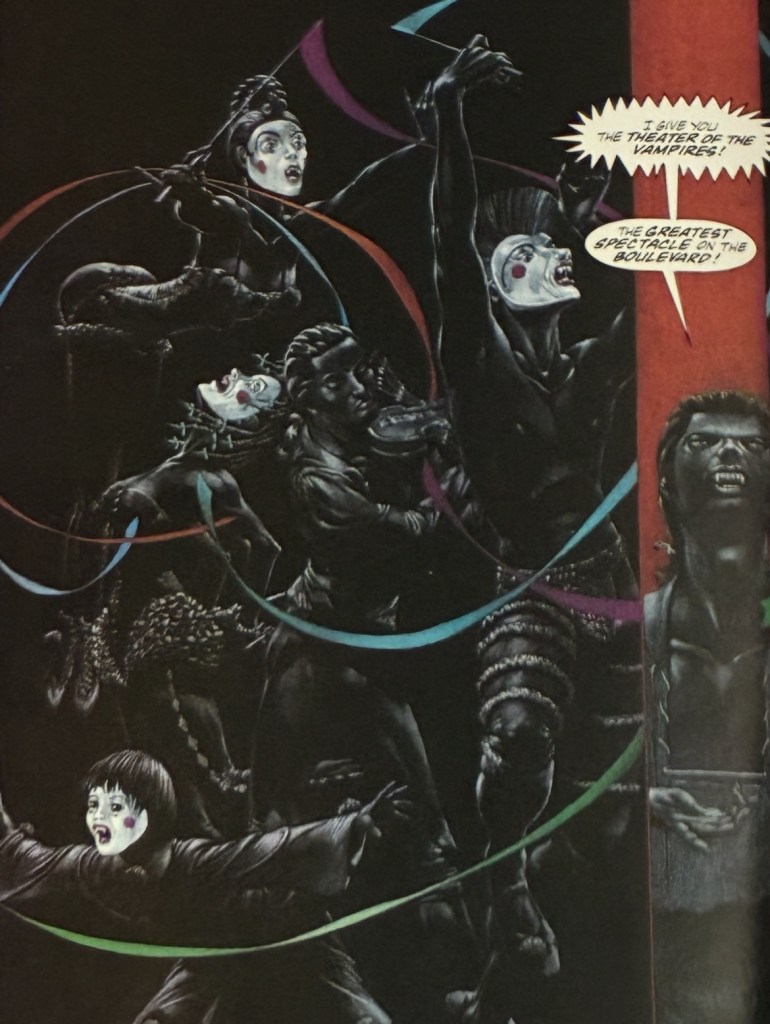

There are a few different reasons why The Vampire Lestat is an important lynch pin in The Vampire Chronicles. One of them is that many of the metaphysical basics are established. This includes all the vampiric cryptobiology details as well as other world-building precedents.

The turning of Lestat’s mother is one of these moments. It states explicitly what the relationship dynamics in Interview With The Vampire said implicitly. Transforming into a vampire divests one of the incidentals of human society and makes them relatable as pure individuals.

Or starkly unrelatable and hostile to each other. But when two vampires connect, they connect simply as one soul to another. As he transforms his mother, Lestat feels the baggage of a lifetime of mother-son dynamics fall away and sees Gabrielle for who she truly is, irrespective of her role as a mother or a wife. Ironically, this spiritual nakedness causes new relational roles- that of lovers.

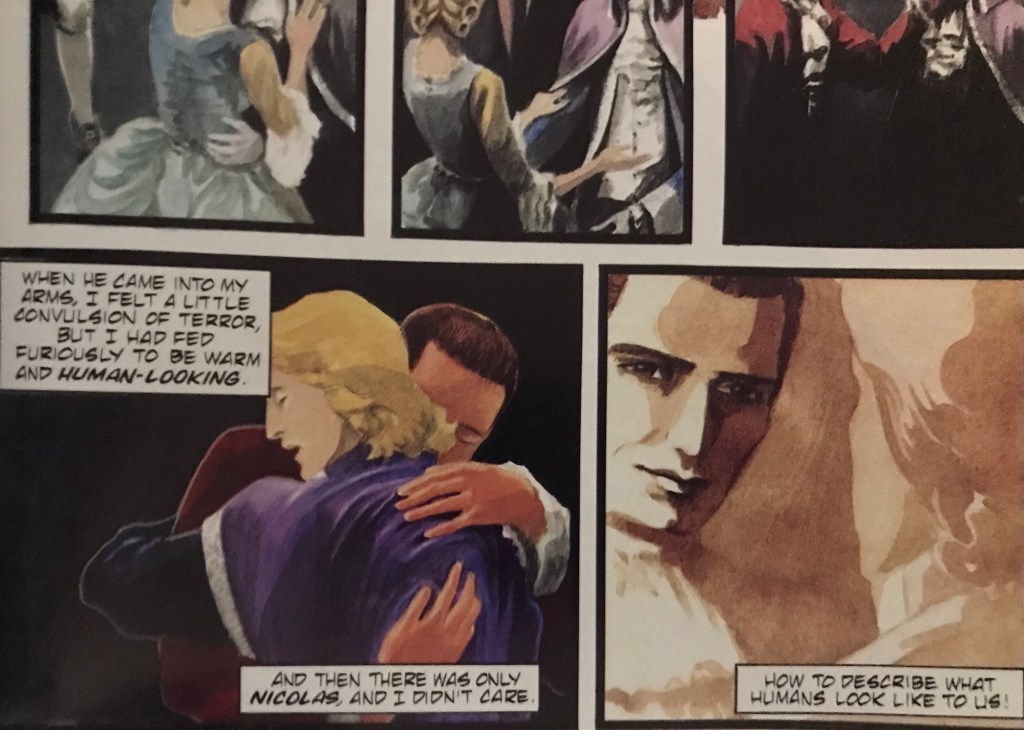

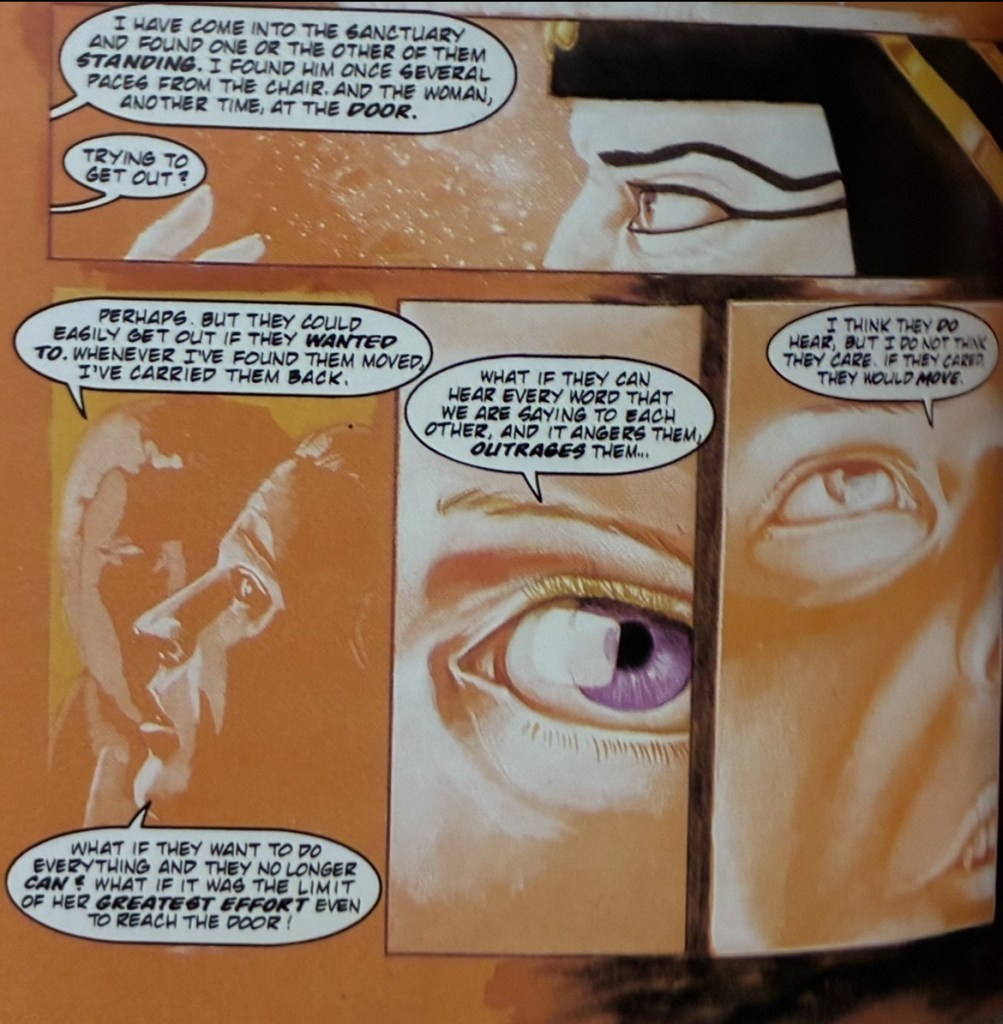

The turning of Nicolas was particularly well done. Earlier, with Gabrielle, the divestment of all human societal roles caused the formation of new roles. For Nicolas, that was exactly what he couldn’t bear.

For comparison, consider how different things were even a short time ago. The panels above depict Lestat’s first reunion with Nicolas after he was transformed by Magnus. Yes, Lestat is a young vampire internally-narrating how living, non-prey humans look. But in the panel with the hug, Lestat feels “a little convulsion of terror”. He’s not hungry because he just fed; he just gorged himself to look more human. One wonders if he was afraid of revealing his otherworldly nature, “and then there was only Nicolas, and I didn’t care.”

The ineffability of such a moment lends credence to the post-vampire awakening, as if there really is a divine spark that shines brightest without the trappings of mortal life.

Once Nicolas is turned, though, he discovers the opposite.

The ineffable sweetness of that reunion only happened because of the love between Nicolas and Lestat as young mortal men. Without that context, the abstraction slowly becomes too much for Nicolas. Gabrielle, meanwhile, luxuriates in the freedom.

None of this is spelled out in as many words; it just unfolds. This, like so much, benefits from the structure of the story.

First, Lestat addresses the reader. In this address, Lestat is in a sustained flashback dialogue with both Gabrielle and Nicolas. Later, the narrative conversation happens between Lestat and Armand who is later replaced with Marius. It ends with a more open and chaotic vignette in the present, like the source material.

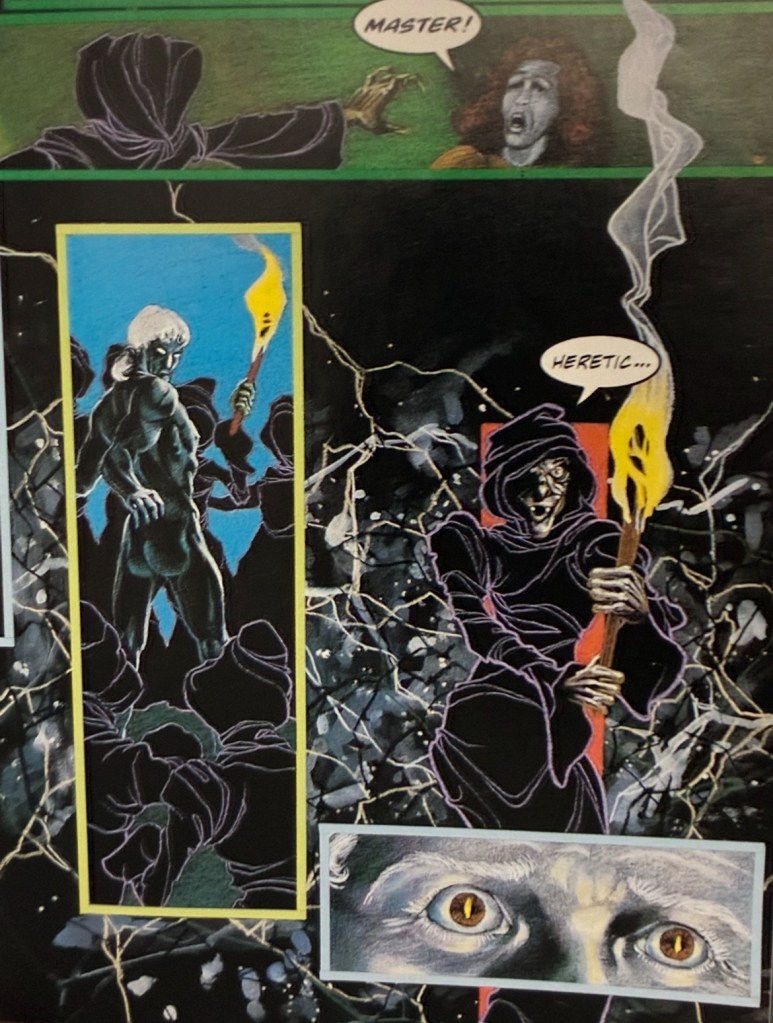

The episodic nature of comic releases also worked out for the best. It enables the book to directly foreground things like the tales of Armand and Marius. The usage of color is more stark and contrasting in these stories than in the events set in the narrative “present” of Lestat’s early years in France and Egypt. Armand’s story regularly contrasts bright and dark colors. Marius’s nested stories have eras of vivid colors not typically seen elsewhere. A long, dark blue section is succeeded by purple and black. Both are eventually replaced with vibrant white, orange and yellow. Obviously this is playing on the dramatic immersion in someone’s internal world, with whole chunks of time recalled with distinct and sequential meaning, colored by emotion.

It feels thematically relevant that Marius’s tale in Egypt was- for many vampires -the most eye-catching part of Lestat’s book, music and music videos. With half-formed thoughts of Nicki in the back of his mind, Lestat acts on an impulse to play the violin for Akasha. Akasha offers her blood and Enkil attacks him, yet neither of Those Who Must Be Kept shift out of their white, statue-like torpor. Lestat is now a direct participant in Marius’s tale of the vampiric parents.

The stories of Armand and Marius are colored by the emotions of their narrators yet- because of the meta-narrative in the year 1984 -these stark contrasts add credibility to the reactions of the modern vampires.

When I first read The Vampire Lestat, all of these moments were equally foregrounded for me. Those parts of the story shaped my belief that- no matter what genre people put Anne Rice into -she is fundamentally a fantasy novelist. What is the tale of Akasha and Enkil but a fantasy plot point, framed by world history?

There is a certain kind of reader, though, that will never stop thinking of a digression from the narrative present as non-story material. A visual, episodic medium is an ideal way of making these digressions take up their own space. Lestat’s meta-narrative conversations with Nicolas and Gabrielle happened on a similar basis; it’s just less obvious because those three characters knew each other as both humans and vampires.

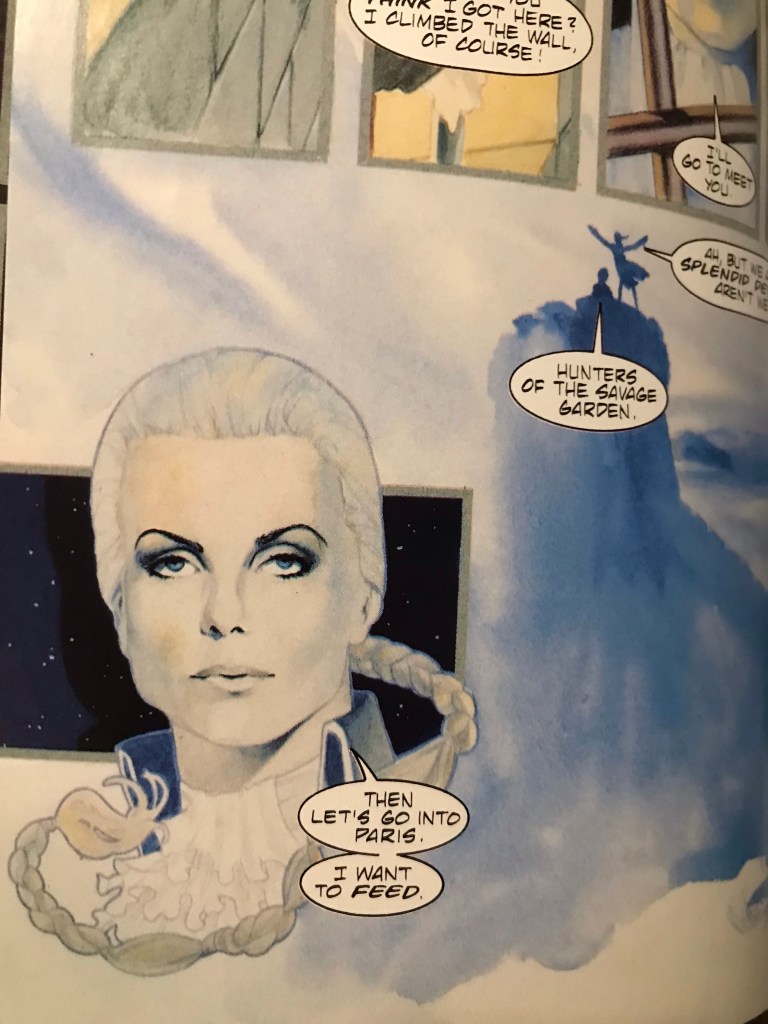

What is exemplified in those two earlier pages with Gabrielle (“During all this misery…” & “Hunters of the Savage Garden”) is Lestat’s mental narration contrasted with brief visual digressions. Both of them contain panel arrangements that suggest different events are being referenced. They look like they contain samples of a longer chunk of time but they’re just extremely stark perspectives within the same moment. The “Hunters of the Savage Garden” page shows Lestat and Gabrielle (post-vampire) talking as they leave Magnus’s castle for the night. They are briefly talking on two sides of a metal grate in alternating panels. The starkest contrast with the overall color scheme is the starscape behind Gabrielle when she says “I want to feed.” Nuances like that are tiny but- in a story that’s mostly framed by dialogue -they go a long way toward establishing a balance between the visual nature of comics and the whole ‘neverending interview’ structure.